"I thought not only the 'good morning' but the 'what's that?' and the 'I want that' were pretty easily understood."

"Yes - I came here to comment on how 'good morning', 'what's that?' and 'I want that' were all perfectly clear, at least through that recording and the medium of the internet."

"Her speech was clearer than I expected, too, especially considering she had just woken up. I heard the 'Good morning,' 'What's that,' 'I want that' and I thought she said 'I fell on the floor.'"

"That 'good morning' sounded clearer than I sound when someone wakes me up!"

"She was pretty clear. I understood her."

"Like everyone says, those phrases were very clear!"

"Extremely clear AND right when she was waking up!"

"I could understand everything."

"Great job Schuyler... I can understand you just fine..."

"She speaks a lot more clearly than I imagined she did - I, too, can understand most of what she says."

I knew what people were saying, and I appreciated the sentiments behind the statements, and also the sort of literal truth of what they were saying. Still, at one point, I tried to moderate the tone a little with a "reality check" observation:

Her speech is getting a little clearer as she gets older, which is good news and a little bit of a surprise. She still does much better when you have a fairly good idea what she's likely to be saying. And it's funny how much of what we say in a day falls within the bounds of often-repeated "catch phrases" like "good morning and "i love you".

When she launches into a monologue about something at random and you don't have any context for it, it goes back to being pure Martian. Well, baby steps.

But I knew it was only a matter of time before someone said it:

After reading this blog for so long, I was really surprised at how easy it was to understand Schuyler's speech. Yes, she's missing some consonants, but she is much more understandable than you have been making her sound in your descriptions.

The tone was friendly, but the implied message was clear: I have been misrepresenting the extent of Schuyler's disability.

I was struggling to find the right words to respond to this, but then, two commenters on the blog spelled it out better than I could, and with the added advantage of an outside perspective.

The first was anonymous, not surprising since he/she was discussing a family member:

My dad, who is almost completely disabled and has an overwhelming number of health problems, is a highly intelligent man whose physical problems have begun to overwhelm his brain. Even on very bad days, he has an uncanny ability to appear to be communicating far better than he is actually managing to do.

He does this in part by accessing rote forms of speech that let people assume that he's responded appropriately, even if he has not actually followed the conversation correctly. People are often poor listeners, and frequently "hear" what they expect to, rather than what was actually said. This doesn't mean, though, that the speaker has been understood.

I am frequently amazed when other people tell me how lucid he is on days when he most certainly is not. The difference is very clear to me, even if others can't see it in the course of the sort of formulaic conversational exchanges that make up most of his day in his nursing home.

I, too, am surprised that some of Schuyler's speech is so clear, but it seems to me that much of what is clear is also very basic. This in no way diminishes the wonder of that clarity, but the ability to say phrases like "good morning" and that wonderful word "Mama" doesn't imply that discussing ideas or other complexities are also possible.

You describe Schuyler so well that it's impossible not to feel that we know her, at least a little. Your writing about her acknowledges the complexities of her character and her life; I don't see that you have in any way implied that her verbal expression is radically different than what we see here.

It's fairly easy to assume what a bouncy, bright child may be saying at a mall, just as it's easy for people to assume that they know what my dad is saying about his day. But it's quite another matter to discuss ideas, feelings, or interpretations when there are physical limitations to speech. And that, I think, you describe very well in your writings.

And Karen is even more direct:

Well, I'm kind of going against the flow here, but I thought Schuyler was understandable if you were listening carefully, if you knew the context of the situation, and if you had a pretty good idea of what she would say. But if I were to listen to an audio recording of her speaking and didn't have any clues as to what she might be speaking about, I would have had a very hard time understanding her. Her "Good morning" in the previous post was clear, but most of what she said was in this post was understandable because of the context. Even with knowing the context of being in a mall, I can't imagine how complicated it would be if she'd said something like, "Hey Dad, did you remember that store we went to the last time we were here? I saw an ad for them on TV last night and they're having a sale on these really cool T-shirts. Can we go there after lunch and get one?"They both understand perfectly. They are both absolutely one hundred percent correct.

And, though it pains me to say this, I didn't think she talked as much as a lot of neuro-typical nine-year-old girls would have in a similar situation. Maybe that's because of her personality. Some kids are more talkative than others. But it could also be because communicating (both verbally and through her BBOW) is frustrating. Certainly it would frustrate me to have to work at something that everyone else seems to do effortlessly. She's a lovely girl, and it's a joy to see and hear her. But I think it seems easy to understand her because a lot of us hear what we want to hear or expect to hear when we're talking to others. It must be hell for her when she wants to bring up a new subject, or have a lengthy in-depth conversation.

I understand the desire to hear clear, intelligible speech coming from Schuyler, and it is undeniable that her verbal communication has improved dramatically since we came to Plano and especially since she began using the Big Box of Words.

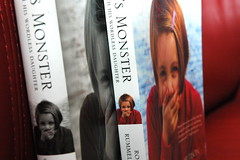

But there's a hard reality to Schuyler's communication, and some real limits to her spoken language, something that goes beyond "missing some consonants". (She's missing most of them, incidentally.) Acknowledging that particular reality doesn't close doors for her, and it doesn't mean giving up on her. The first step to helping Schuyler, however, comes in understanding exactly where she is and what her current limitations are. Wanting or even needing to believe the monster is smaller than it is, well, that's an impulse I understand completely.

But as far as Julie and I are concerned, sizing up that monster is an important first step. We need proper measurements in order to correctly tailor its Ass-beating Suit.