But I don't know, this year feels different. 2008 certainly feels more deserving of a self-indulgent recap, as all personal blog annual recaps are required to be, by law. I believe it's a federal law.

For me personally, it was obviously a significant year, and not just because I was thirty-ten and still inexplicably alive. 2008 was the year that I was published. A book. A real, hardcover, not-printed-at-Kinko's, gigantic New York publishing house, "fuck you, trees" book. I did all that work, I wrote 90,000 words that someone wanted to publish, I went through an editing process that was deceptively painless, and one day a box arrived at my apartment that contained something that no one can ever take away from me now. Last week, ending the year, I received another, similar box, this time with paperback copies of this thing that I did, this thing that seems so unlikely even now.

It was never what I set out to do. I never dreamed that I would get picked up by St. Martin's Press, or that I would see my words published in Good Housekeeping or Wondertime. I never expected to get reviewed in People, or to be featured in newspaper articles or on public radio. I certainly never expected to go on television, in interviews that I loved and others that, well, not so much, and in ones where I talked about my faith, something that I rarely do privately, much less for a live television audience. I didn't write the book so I could give big fancy speeches or return to my college as something besides assistant manager at Kentucky Fried Chicken, and I certainly never anticipated being the guest lecturer at a university. I never thought it would reach this level of fancy pantsedness. I even bought a suit.

I have loved every moment of it, and it has been an incredible adventure, one that I don't expect will repeat itself, no matter what I publish in the future. It's been amazing mostly because my family has been along for the ride. I'm not sure how much Julie enjoys living in the light now, although she's been fantastic about the whole thing, but for Schuyler, it's been an amazing trip. She's developed into an even more confident and sociable little girl, if that's possible.

More importantly, I believe the attention from the book has shown Schuyler that she really is unique and different, but far from being a freak, she's a rare creature of beauty and spark. She knows she's broken, but she's also learning that people love her not just despite that, but because of how she deals with it. She understands that she has a monster; suggesting or pretending otherwise is an insult to her, as far as I'm concerned. But because of the book and the attention she's received from it, I like to believe that she also sees that it is in taming that monster and making it small that she has become her own kind of perfect.

And that's really why I wrote the book, and why I wanted to get it out in the world, even if it had only sold 500 copies and gotten remaindered in six months. (Note: It's doing a little better than that, I'm happy to report.) It was my love letter to Schuyler. It was my insurance policy, the thing that would stand for me if I ever got hit by a bus or killed by internet stalkers. She will always have the book, and so in that respect, 2008 was the best year of my life with Schuyler. No matter what, she'll always have that, and will always know what she meant to me, and how much I admire her.

This was a good year for me for making new friends and reconnecting with old ones, mostly because of the book. It hasn't been perfect, of course. I believe resentment is probably responsible for finally killing off at least one friendship, albeit one that was admittedly on tottering legs anyway. I think that's too bad; it's not as if I took someone else's shot at publication away in achieving mine. But for the most part, I've met some really amazing writers over the past year, and I've reconnected with old friends from high school who saw the articles in People and Good Housekeeping. (And just why are people my age reading Good Housekeeping, anyway? Oh, yeah, we're the target demographic now. Time, you suck.) Best of all, I've watched some old but casual friendships deepen and flourish. My friendships are a little like a garden, I suppose. The weeding's not much fun, but it's the new blossoms that take my breath away and remind me of what's good in the world.

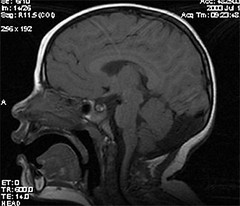

I have no idea what to expect from 2009. The year begins with the paperback release of my book, but the day before, it also sees Schuyler's return to the world of doctors and specialists and questions. The other day, Julie very quietly said, "I think Schuyler's PMG is starting to manifest itself more," and I think she might be right. We've both seen more of her little spells, and she's starting to have a slight increase in difficulties with her fine motor skills. She's only signing with her left hand now, for example, and her handwriting seems to be challenging her a little more, too. If I had to sit down and face this thing head-on, I might be forced to admit that when I think of this new year, I am filled with a dread, a persistent feeling that something's coming, and not something nice. I'm Schuyler's father, and I'm prone to considering all the worst-case scenarios, I know. But I also know Schuyler, better than anyone else in the world save one. When she starts to experience changes, we see it. I think we've already done more than enough to convince the world that we know what we're talking about, and yet I suspect we're about to be right back in that swamp again, the one where we're the idiot parents and someone else is The Expert. This time, I think we'll be ready.

Most of all, however, I think that no matter how rough 2009 might turn out to be or how big the monster grows, once again it will be Schuyler who will show me the way. She continues to be the strong one, and the smart one, and most of all the tenacious fighter. I see the monster again after so much quiet time, and I despair. Schuyler sees an ass that she needs to cheerfully kick. That will always be the difference between us, and perhaps it's the way it's supposed to be.

I think about that a lot. How Things Are Supposed To Be. I've never thought this was it, of course. So many people see Schuyler through their own prism, and so she becomes and angel or a savior or whatever she needs to be for them. As she steps into a new year as a nine year-old, Schuyler is everything she is perceived to be, and much more. She's a broken yet priceless doll, sadly incomplete and yet more perfect and beautiful because of it. She's an otherworldly being who speaks in a beautiful but foreign tongue, but she's also the quintessential nine year-old girl who lives in Chuck Taylors and wants to be Kim Possible. She's a chaotic tornado of energy who bristles at authority and thrives on change. Schuyler doesn't need anyone to teach her about God or Jesus or anyone else who has failed her, and yet she's a child of God, like the rest of us. She's a child who deserves an explanation from that Divine Bully, but to whom it will probably never even occur to ask.

As the new year dawns, it's Schuyler whom I'll be watching, and following, and if she can make her way through this grand rough world, one that both fails her and thrills her at ever turn, then I suppose the rest of us can, too.

Besides, she's the only person who likes my moustache, even if just as an object of amusement.

For last year's words belong to last year's language

And next year's words await another voice.

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

~T.S. Eliot