If you liked my last entry but found the whole "left-to-right eyeball tracking" thing to be a distraction, you'll be pleased to know that QN Podcast (The Podcast Formerly Known as Quirky Nomads) featured the entry in their March 9th edition, "Ambush". Thanks, Sage!

You'll be even more happy to know that it's not my yokelly voice this time. It's encouraging how much smarter I sound when someone else is reading.

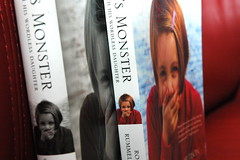

Schuyler is my weird and wonderful monster-slayer. Together we have many adventures.

March 10, 2009

March 3, 2009

Ambush my heart

Sometimes it sort of sneaks up on us.

Schuyler came home from school without her speech device today, which as you can imagine is a pretty big deal. We were stern with her, in that way that is probably a necessary part of the parenting process but which makes me a little queasy, and we found ourselves back at her school at seven o'clock at night. A janitor let us in, and Schuyler took us to her mainstream classroom. And there it was, the Big Box of Words, along with her lunchbox and a few other items that should have come home with her.

We led her miserably back to the car, lecturing her sternly the whole way. When we got to the car, we talked to her about the importance of having her device with her at all times, both because of her communication needs and the fact that, yeah, she's a nine year-old kid walking around with a $7500 piece of electronic equipment.

Throughout the questions and the admonishments, Schuyler sat quietly, her face downcast and sad. I can't look at her face when I talk to her in those moments, because I'll fold like a house of cards if I see those eyes.

It occurred to Julie that if Schuyler was leaving her device in her last classroom, she must not be using it in her after school program. That's not incredibly surprising since they mostly play and run around, in a rough and tumble environment that doesn't lend itself to using the BBoW. But in addition to any emergency communication needs, Schuyler also does her homework after school, so she needed to have the device nearby and accessible.

"Do you ever even use your device after school?" Julie asked her.

"No," Schuyler answered sadly.

"No? Why not?"

Schuyler hesitated, then started punching buttons on the device. When she was done, she looked up at us, with an expression of sadness and maybe even defeat, a look I very rarely see in her eyes. Rarely, but occasionally. When I see it, I take notice. She touched the speech button.

"They don't know I can't talk."

Yeah, sometimes it sneaks up on us.

I just started to cry, out of nowhere. Julie held it together a little longer, but not long. "She knows," Julie said. "She really understands, doesn't she?"

There was nothing left to say after that. I gave Schuyler a hug, a long one, and we drove in silence to the Purple Cow, her favorite restaurant.

Later, I asked Schuyler who she was talking about. "Who doesn't know you can't talk?"

She signed "friends".

And so it turns out that a father's heart can break twice in one night.

Schuyler came home from school without her speech device today, which as you can imagine is a pretty big deal. We were stern with her, in that way that is probably a necessary part of the parenting process but which makes me a little queasy, and we found ourselves back at her school at seven o'clock at night. A janitor let us in, and Schuyler took us to her mainstream classroom. And there it was, the Big Box of Words, along with her lunchbox and a few other items that should have come home with her.

We led her miserably back to the car, lecturing her sternly the whole way. When we got to the car, we talked to her about the importance of having her device with her at all times, both because of her communication needs and the fact that, yeah, she's a nine year-old kid walking around with a $7500 piece of electronic equipment.

Throughout the questions and the admonishments, Schuyler sat quietly, her face downcast and sad. I can't look at her face when I talk to her in those moments, because I'll fold like a house of cards if I see those eyes.

It occurred to Julie that if Schuyler was leaving her device in her last classroom, she must not be using it in her after school program. That's not incredibly surprising since they mostly play and run around, in a rough and tumble environment that doesn't lend itself to using the BBoW. But in addition to any emergency communication needs, Schuyler also does her homework after school, so she needed to have the device nearby and accessible.

"Do you ever even use your device after school?" Julie asked her.

"No," Schuyler answered sadly.

"No? Why not?"

Schuyler hesitated, then started punching buttons on the device. When she was done, she looked up at us, with an expression of sadness and maybe even defeat, a look I very rarely see in her eyes. Rarely, but occasionally. When I see it, I take notice. She touched the speech button.

"They don't know I can't talk."

Yeah, sometimes it sneaks up on us.

I just started to cry, out of nowhere. Julie held it together a little longer, but not long. "She knows," Julie said. "She really understands, doesn't she?"

There was nothing left to say after that. I gave Schuyler a hug, a long one, and we drove in silence to the Purple Cow, her favorite restaurant.

Later, I asked Schuyler who she was talking about. "Who doesn't know you can't talk?"

She signed "friends".

And so it turns out that a father's heart can break twice in one night.

March 1, 2009

Reality Check

As soon as I posted video of Schuyler communicating, the comments began. There were a lot of them saying something similar.

"I thought not only the 'good morning' but the 'what's that?' and the 'I want that' were pretty easily understood."

"Yes - I came here to comment on how 'good morning', 'what's that?' and 'I want that' were all perfectly clear, at least through that recording and the medium of the internet."

"Her speech was clearer than I expected, too, especially considering she had just woken up. I heard the 'Good morning,' 'What's that,' 'I want that' and I thought she said 'I fell on the floor.'"

"That 'good morning' sounded clearer than I sound when someone wakes me up!"

"She was pretty clear. I understood her."

"Like everyone says, those phrases were very clear!"

"Extremely clear AND right when she was waking up!"

"I could understand everything."

"Great job Schuyler... I can understand you just fine..."

"She speaks a lot more clearly than I imagined she did - I, too, can understand most of what she says."

I knew what people were saying, and I appreciated the sentiments behind the statements, and also the sort of literal truth of what they were saying. Still, at one point, I tried to moderate the tone a little with a "reality check" observation:

But I knew it was only a matter of time before someone said it:

The tone was friendly, but the implied message was clear: I have been misrepresenting the extent of Schuyler's disability.

I was struggling to find the right words to respond to this, but then, two commenters on the blog spelled it out better than I could, and with the added advantage of an outside perspective.

The first was anonymous, not surprising since he/she was discussing a family member:

And Karen is even more direct:

I understand the desire to hear clear, intelligible speech coming from Schuyler, and it is undeniable that her verbal communication has improved dramatically since we came to Plano and especially since she began using the Big Box of Words.

But there's a hard reality to Schuyler's communication, and some real limits to her spoken language, something that goes beyond "missing some consonants". (She's missing most of them, incidentally.) Acknowledging that particular reality doesn't close doors for her, and it doesn't mean giving up on her. The first step to helping Schuyler, however, comes in understanding exactly where she is and what her current limitations are. Wanting or even needing to believe the monster is smaller than it is, well, that's an impulse I understand completely.

But as far as Julie and I are concerned, sizing up that monster is an important first step. We need proper measurements in order to correctly tailor its Ass-beating Suit.

"I thought not only the 'good morning' but the 'what's that?' and the 'I want that' were pretty easily understood."

"Yes - I came here to comment on how 'good morning', 'what's that?' and 'I want that' were all perfectly clear, at least through that recording and the medium of the internet."

"Her speech was clearer than I expected, too, especially considering she had just woken up. I heard the 'Good morning,' 'What's that,' 'I want that' and I thought she said 'I fell on the floor.'"

"That 'good morning' sounded clearer than I sound when someone wakes me up!"

"She was pretty clear. I understood her."

"Like everyone says, those phrases were very clear!"

"Extremely clear AND right when she was waking up!"

"I could understand everything."

"Great job Schuyler... I can understand you just fine..."

"She speaks a lot more clearly than I imagined she did - I, too, can understand most of what she says."

I knew what people were saying, and I appreciated the sentiments behind the statements, and also the sort of literal truth of what they were saying. Still, at one point, I tried to moderate the tone a little with a "reality check" observation:

Her speech is getting a little clearer as she gets older, which is good news and a little bit of a surprise. She still does much better when you have a fairly good idea what she's likely to be saying. And it's funny how much of what we say in a day falls within the bounds of often-repeated "catch phrases" like "good morning and "i love you".

When she launches into a monologue about something at random and you don't have any context for it, it goes back to being pure Martian. Well, baby steps.

But I knew it was only a matter of time before someone said it:

After reading this blog for so long, I was really surprised at how easy it was to understand Schuyler's speech. Yes, she's missing some consonants, but she is much more understandable than you have been making her sound in your descriptions.

The tone was friendly, but the implied message was clear: I have been misrepresenting the extent of Schuyler's disability.

I was struggling to find the right words to respond to this, but then, two commenters on the blog spelled it out better than I could, and with the added advantage of an outside perspective.

The first was anonymous, not surprising since he/she was discussing a family member:

My dad, who is almost completely disabled and has an overwhelming number of health problems, is a highly intelligent man whose physical problems have begun to overwhelm his brain. Even on very bad days, he has an uncanny ability to appear to be communicating far better than he is actually managing to do.

He does this in part by accessing rote forms of speech that let people assume that he's responded appropriately, even if he has not actually followed the conversation correctly. People are often poor listeners, and frequently "hear" what they expect to, rather than what was actually said. This doesn't mean, though, that the speaker has been understood.

I am frequently amazed when other people tell me how lucid he is on days when he most certainly is not. The difference is very clear to me, even if others can't see it in the course of the sort of formulaic conversational exchanges that make up most of his day in his nursing home.

I, too, am surprised that some of Schuyler's speech is so clear, but it seems to me that much of what is clear is also very basic. This in no way diminishes the wonder of that clarity, but the ability to say phrases like "good morning" and that wonderful word "Mama" doesn't imply that discussing ideas or other complexities are also possible.

You describe Schuyler so well that it's impossible not to feel that we know her, at least a little. Your writing about her acknowledges the complexities of her character and her life; I don't see that you have in any way implied that her verbal expression is radically different than what we see here.

It's fairly easy to assume what a bouncy, bright child may be saying at a mall, just as it's easy for people to assume that they know what my dad is saying about his day. But it's quite another matter to discuss ideas, feelings, or interpretations when there are physical limitations to speech. And that, I think, you describe very well in your writings.

And Karen is even more direct:

Well, I'm kind of going against the flow here, but I thought Schuyler was understandable if you were listening carefully, if you knew the context of the situation, and if you had a pretty good idea of what she would say. But if I were to listen to an audio recording of her speaking and didn't have any clues as to what she might be speaking about, I would have had a very hard time understanding her. Her "Good morning" in the previous post was clear, but most of what she said was in this post was understandable because of the context. Even with knowing the context of being in a mall, I can't imagine how complicated it would be if she'd said something like, "Hey Dad, did you remember that store we went to the last time we were here? I saw an ad for them on TV last night and they're having a sale on these really cool T-shirts. Can we go there after lunch and get one?"They both understand perfectly. They are both absolutely one hundred percent correct.

And, though it pains me to say this, I didn't think she talked as much as a lot of neuro-typical nine-year-old girls would have in a similar situation. Maybe that's because of her personality. Some kids are more talkative than others. But it could also be because communicating (both verbally and through her BBOW) is frustrating. Certainly it would frustrate me to have to work at something that everyone else seems to do effortlessly. She's a lovely girl, and it's a joy to see and hear her. But I think it seems easy to understand her because a lot of us hear what we want to hear or expect to hear when we're talking to others. It must be hell for her when she wants to bring up a new subject, or have a lengthy in-depth conversation.

I understand the desire to hear clear, intelligible speech coming from Schuyler, and it is undeniable that her verbal communication has improved dramatically since we came to Plano and especially since she began using the Big Box of Words.

But there's a hard reality to Schuyler's communication, and some real limits to her spoken language, something that goes beyond "missing some consonants". (She's missing most of them, incidentally.) Acknowledging that particular reality doesn't close doors for her, and it doesn't mean giving up on her. The first step to helping Schuyler, however, comes in understanding exactly where she is and what her current limitations are. Wanting or even needing to believe the monster is smaller than it is, well, that's an impulse I understand completely.

But as far as Julie and I are concerned, sizing up that monster is an important first step. We need proper measurements in order to correctly tailor its Ass-beating Suit.

February 28, 2009

Mall monster

More video. Here's a peek at how Schuyler communicates in the course of a typical evening. She tells a little about herself, orders her dinner at a restaurant, and takes a slightly queasy spin with the camera.

February 26, 2009

Morning monster

I got a fun new Flip Video Mino camera (courtesy of Circuit City's sorrow), and sprung it on Schuyler this morning. She wasn't even remotely interested in getting out of bed until she saw a new gadget. She is her father's daughter.

(Listen for a surprisingly clear "Good Morning".)

(Listen for a surprisingly clear "Good Morning".)

February 25, 2009

"a point upon a map of fog..."

Note to my delicate and sensitive readers:

So there's a part of my San Francisco Adventure Story that involves injury, blood, general nastiness, pain and even partial accidental amputation. I'll save that part for the end, so that those of you prone to the vapors can stop reading. (And also so my extra-nasty readers can skip ahead. You know who you are.)

My trip to the San Francisco Bay Area was, I believe, an outstanding success. I managed to schedule a surprising amount of productive-type behavior into five days, and I got to see a lot of what is an absolutely beautiful city, even when it's shrouded in rain. Which it was, by the way, beginning the day I arrived and lifting, I suspect, at roughly the same hour that my return flight took off.

The night before I left Texas, the Dallas area was rocked by tornados (tornadi?), so I don't know, maybe it's me.

I'd be the worst sort of jackass guest if I didn't stop right now and express my gratitude to Ian Golder and Monique van den Berg for putting me up (and putting up with me) for the duration of my stay. Five days is a long time to have a house guest, but they never complained and not even once gently suggested that perhaps I'd be more comfortable if I got a room at a hotel or one of the city's many fine homeless shelters. More importantly, their giant dog never tried to eat me, which I also consider the sign of a polite host.

(Actually, the truth is that I have something of a Bigdogaphobia, thanks to a horrible childhood attack by, ironically, the one breed of big dog that doesn't seem to bother me now, a Great Dane. I used to have scars on the back of my legs that told the tale, but I am far too old and fat to be able to look back there now. My thanks to Ian and Monique, and Goulash the Giant But Gentle Dogzilla, for being sensitive to my weird dog issues.)

The first night I was in town, I spoke to Monique's writing class at the College of San Mateo. If you're wondering what possible situation I might consider to be absolutely surreal, it might be speaking to a class that is studying personal narrative by way of my own book. Yes, my book was the assigned text; the students were reading it and taking tests about it and having classroom discussions about it. I could try to spin that experience into some fancy, existential parable, but in all honesty, it was just extremely damn cool to be me that evening. I highly recommend it.

I agreed to help workshop some of the personal narratives written by the students, and to be honest, I was nervous about it. I had no idea what I was going to say if I had to workshop an essay that was, well, bad. But here's the thing: none of them were. Everything I read had a real sense of voice; everything had something to say and a concept of how they wanted to express it. I was legitimately impressed, and only resented their youth a little. Damn kids.

The next day, we visited schools. You knew that already.

I'd never been to San Francisco before, but there are a number of people in the area whom I knew but had never met, in that nerdy internet way that was weird a decade ago but is just now The Way Things Are in the World. My signing at Book Passage in Corte Madera gave me the opportunity to meet some of them in the flesh, as well as see some people I'd met previously and at least one friend from high school. I know I'm going to screw this up and forget someone, but I'd like to thank Shannon, Ian & Monique, Annie, Kate, Alison, Halsted, Kara, Char, and the AMAZING Edith Meyer, who once again showed up with food, this time cookies, shortbread and a lemon loaf that I think I would have knocked down an old person to get to.

Most of all, however, there were two other special guests. Courtesy of Skype and a good sound system set up by Dana, the awesome events person from Book Passage, Julie and Schuyler appeared on my laptop and answered questions and generally charmed the pants off of everyone. So if you weren't there, well, you missed a lot of charmed, pantsless people. Your loss.

I had a great time in San Francisco, and I'd love to return soon. There's a possibility that Schuyler might attend a summer camp for kids who use Big Boxes of Words, although I might have to discover buried treasure or lost mob money to make that a reality.

I hope it happens.

Okay, I mean it now. Tender-hearts stop reading now. I'm serious. If you don't like the rest of this, don't leave me any crybaby comments. You've been warned.

So yeah, I cut off the end of my finger.

The morning I left for California, I was packing my toiletries and had already put my razor in a side pocket of my little bathroom bag. I decided that it would be a good idea to store my toothbrush in the same pocket (NOTE: This was not actually a good idea), and as I pushed my toothbrush in, it stuck on something, my hand slipped, and my middle finger (aka "The Bird") on my right hand made a rather abrupt and rude introduction to the little Precision Trimmer blade on the top edge of my razor, which if you're into detail, is that funky five-blade "Fusion Power" thing from Gillette.

(Because, you know, it has five blades. How could I use something that just had four, or even three blades -- pshaw! -- all the while KNOWING that there were five blades out there, PLUS that one nasty little trimmer blade on top? Get fucking serious.)

I just went to the Gillette site to see what that little top blade is called, and ran across the following line in the ad: "So comfortable, you barely feel the blades."

I felt the blade.

Now, before you begin to wonder (as you inevitably will) if I immediately went to the emergency room, well, here's the thing. My plane was leaving in about an hour and a half. You just read about the wonderful time I had in San Francisco, and also how many professional commitments I had there. I couldn't just NOT go, all because I cut myself with my razor, and not even shaving but PACKING.

Also, in my own defense (and Julie can queasily back me up on this), it bled. A lot. So much so that I couldn't actually see what I had done. It hurt more than I thought a cut should hurt, and it would not stop bleeding for anything, no matter how much pressure I put on it. But still, I just thought it was a deep cut, right? And when we bandaged it up tightly, the pressure made the bleeding stop. I figured, it just needs some time to settle down. So we threw my bags in the car and drove to the airport, my finger hurting wildly but no longer squirting blood like a Monty Python sketch.

It wasn't until I got past security that I noticed that the bleeding had begun again, seeping through the bandages like, well, like a poorly bandaged wound that really should have been seen by a doctor. If before was a bad time to go have it looked at, then sitting outside my gate with my shoes off wasn't much better. I found a bathroom, decided against removing the bandages (which I still think was probably a smart move on my part, and one that my fellow travelers and bathroom-users would probably agree with) and simply applied MORE bandages on top on the poor little Dutchboy-like original strips that were bravely losing the fight against the flood.

Surprisingly, this second bit of first aid (would that make it second aid?) held, and I made my flight without incident. It wasn't until I attempted to change the bandages before class that I realized how bad it was.

Because it bled again. Badly. And now I saw why.

Okay, so first of all, sit down. Then imagine the very tip of your finger, or my finger really, if that makes you feel better about it. Imagine a piece about the size of a dime (which constitutes most of the tip of your finger, really) and about the thickness of two quarters. Now imagine it connected by a tiny piece of skin. Now imagine it NO LONGER connected by that tiny piece of skin. Imagine it instead stuck to the inside of a bloody bandage, a small not-bloody circle in the middle of a brownish-red tragedy.

And if you're REALLY into detail, also imagine taking your killer razor out of your bag to inexplicably use it against your own stubbly face, despite the fact that it has tasted human blood and may just want more more more. Upon examination, you find that it is surprisingly not at all bloody, because when you cut yourself, your "Ow ow, holy shit, ow motherfucker OW!" reflex kicked in quickly enough to get you to the sink before any real bleeding began. What you do find is what appears to be a small piece of clear plastic stuck in the blades. But when you fish it out, you remember that most clear plastic doesn't have little fingerprint ridges in it. Then you sit down again. And maybe not eat for the rest of the day.

Apparently I cut it twice. One was the big cut, and one was a little bit shaved off the tip, waiting for me to discover it later.

So yeah. I cut off the end of my finger.

Now, I didn't cut off a major, life-changing chunk of my finger. I'll have a flat spot, that's certain, but I can still count to ten and Schuyler can still paint all my fingernails. Still, the cut went deep into that part of the skin where the nerves live, and they do not like being exposed like that. Two weeks after the cut, it is healing up nicely (amazingly, no infection, which goes to show that God really does protect children and stupid people), but you know what?

It still hurts. A lot.

It looks sort of cool, though. I'll leave that to your imagination.

My trip to the San Francisco Bay Area was, I believe, an outstanding success. I managed to schedule a surprising amount of productive-type behavior into five days, and I got to see a lot of what is an absolutely beautiful city, even when it's shrouded in rain. Which it was, by the way, beginning the day I arrived and lifting, I suspect, at roughly the same hour that my return flight took off.

The night before I left Texas, the Dallas area was rocked by tornados (tornadi?), so I don't know, maybe it's me.

I'd be the worst sort of jackass guest if I didn't stop right now and express my gratitude to Ian Golder and Monique van den Berg for putting me up (and putting up with me) for the duration of my stay. Five days is a long time to have a house guest, but they never complained and not even once gently suggested that perhaps I'd be more comfortable if I got a room at a hotel or one of the city's many fine homeless shelters. More importantly, their giant dog never tried to eat me, which I also consider the sign of a polite host.

(Actually, the truth is that I have something of a Bigdogaphobia, thanks to a horrible childhood attack by, ironically, the one breed of big dog that doesn't seem to bother me now, a Great Dane. I used to have scars on the back of my legs that told the tale, but I am far too old and fat to be able to look back there now. My thanks to Ian and Monique, and Goulash the Giant But Gentle Dogzilla, for being sensitive to my weird dog issues.)

The first night I was in town, I spoke to Monique's writing class at the College of San Mateo. If you're wondering what possible situation I might consider to be absolutely surreal, it might be speaking to a class that is studying personal narrative by way of my own book. Yes, my book was the assigned text; the students were reading it and taking tests about it and having classroom discussions about it. I could try to spin that experience into some fancy, existential parable, but in all honesty, it was just extremely damn cool to be me that evening. I highly recommend it.

I agreed to help workshop some of the personal narratives written by the students, and to be honest, I was nervous about it. I had no idea what I was going to say if I had to workshop an essay that was, well, bad. But here's the thing: none of them were. Everything I read had a real sense of voice; everything had something to say and a concept of how they wanted to express it. I was legitimately impressed, and only resented their youth a little. Damn kids.

The next day, we visited schools. You knew that already.

* * *

(photo by Monique van den Berg)

I'd never been to San Francisco before, but there are a number of people in the area whom I knew but had never met, in that nerdy internet way that was weird a decade ago but is just now The Way Things Are in the World. My signing at Book Passage in Corte Madera gave me the opportunity to meet some of them in the flesh, as well as see some people I'd met previously and at least one friend from high school. I know I'm going to screw this up and forget someone, but I'd like to thank Shannon, Ian & Monique, Annie, Kate, Alison, Halsted, Kara, Char, and the AMAZING Edith Meyer, who once again showed up with food, this time cookies, shortbread and a lemon loaf that I think I would have knocked down an old person to get to.

Most of all, however, there were two other special guests. Courtesy of Skype and a good sound system set up by Dana, the awesome events person from Book Passage, Julie and Schuyler appeared on my laptop and answered questions and generally charmed the pants off of everyone. So if you weren't there, well, you missed a lot of charmed, pantsless people. Your loss.

(photo by Shannon Kokoska)

* * *

The rest of my visit was vacation, really. We went to the Big Basin Redwoods State Park and saw many a mighty tree, and while I took lots of photos, it's impossible to get a sense of just how gigantic some of them really were. In person, it was "Holy shit, that's a big goddamn redwood!" When you look at the photos, it's more like "Oh, look. A pretty tree."

My last day in San Francisco was spent sightseeing in the city with Monique and attending a concert by the San Francisco Symphony, which was Monique's amazing Christmas present to me. The performance was conducted by Charles Dutoit, one of my favorite conductors who, with the Montreal Symphony, produced some of the best and most enduring recordings of the last thirty years. San Francisco Symphony performed Debussy's "Oh, look. A pretty deer.", Stravinsky's Symphony in C, and closed with Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, which is frankly a much better piece that R-K really had any right to compose, based on the rest of his output. Don't get me wrong, Rimsky-Korsakov was a brilliant orchestrator and wrote some fine music, by golly, but in Scheherazade, he really stepped it up. He did us hyphenates proud.

And of course, we visited the Pirate Supply Store at 826 Valencia, which (for zoning purposes) serves as a legitimate business front for the writing center founded by Dave Eggers. I bought pirate flags and a t-shirt and the obligatory eye patch for Schuyler and Julie.

(photo by Monique van den Berg)

My last day in San Francisco was spent sightseeing in the city with Monique and attending a concert by the San Francisco Symphony, which was Monique's amazing Christmas present to me. The performance was conducted by Charles Dutoit, one of my favorite conductors who, with the Montreal Symphony, produced some of the best and most enduring recordings of the last thirty years. San Francisco Symphony performed Debussy's "Oh, look. A pretty deer.", Stravinsky's Symphony in C, and closed with Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, which is frankly a much better piece that R-K really had any right to compose, based on the rest of his output. Don't get me wrong, Rimsky-Korsakov was a brilliant orchestrator and wrote some fine music, by golly, but in Scheherazade, he really stepped it up. He did us hyphenates proud.

And of course, we visited the Pirate Supply Store at 826 Valencia, which (for zoning purposes) serves as a legitimate business front for the writing center founded by Dave Eggers. I bought pirate flags and a t-shirt and the obligatory eye patch for Schuyler and Julie.

"Pillage before plunder, what a blunder.

Plunder before pillage, mission fulfillage."

I had a great time in San Francisco, and I'd love to return soon. There's a possibility that Schuyler might attend a summer camp for kids who use Big Boxes of Words, although I might have to discover buried treasure or lost mob money to make that a reality.

I hope it happens.

Okay, I mean it now. Tender-hearts stop reading now. I'm serious. If you don't like the rest of this, don't leave me any crybaby comments. You've been warned.

So yeah, I cut off the end of my finger.

The morning I left for California, I was packing my toiletries and had already put my razor in a side pocket of my little bathroom bag. I decided that it would be a good idea to store my toothbrush in the same pocket (NOTE: This was not actually a good idea), and as I pushed my toothbrush in, it stuck on something, my hand slipped, and my middle finger (aka "The Bird") on my right hand made a rather abrupt and rude introduction to the little Precision Trimmer blade on the top edge of my razor, which if you're into detail, is that funky five-blade "Fusion Power" thing from Gillette.

(Because, you know, it has five blades. How could I use something that just had four, or even three blades -- pshaw! -- all the while KNOWING that there were five blades out there, PLUS that one nasty little trimmer blade on top? Get fucking serious.)

I just went to the Gillette site to see what that little top blade is called, and ran across the following line in the ad: "So comfortable, you barely feel the blades."

I felt the blade.

Now, before you begin to wonder (as you inevitably will) if I immediately went to the emergency room, well, here's the thing. My plane was leaving in about an hour and a half. You just read about the wonderful time I had in San Francisco, and also how many professional commitments I had there. I couldn't just NOT go, all because I cut myself with my razor, and not even shaving but PACKING.

Also, in my own defense (and Julie can queasily back me up on this), it bled. A lot. So much so that I couldn't actually see what I had done. It hurt more than I thought a cut should hurt, and it would not stop bleeding for anything, no matter how much pressure I put on it. But still, I just thought it was a deep cut, right? And when we bandaged it up tightly, the pressure made the bleeding stop. I figured, it just needs some time to settle down. So we threw my bags in the car and drove to the airport, my finger hurting wildly but no longer squirting blood like a Monty Python sketch.

It wasn't until I got past security that I noticed that the bleeding had begun again, seeping through the bandages like, well, like a poorly bandaged wound that really should have been seen by a doctor. If before was a bad time to go have it looked at, then sitting outside my gate with my shoes off wasn't much better. I found a bathroom, decided against removing the bandages (which I still think was probably a smart move on my part, and one that my fellow travelers and bathroom-users would probably agree with) and simply applied MORE bandages on top on the poor little Dutchboy-like original strips that were bravely losing the fight against the flood.

Surprisingly, this second bit of first aid (would that make it second aid?) held, and I made my flight without incident. It wasn't until I attempted to change the bandages before class that I realized how bad it was.

Because it bled again. Badly. And now I saw why.

Okay, so first of all, sit down. Then imagine the very tip of your finger, or my finger really, if that makes you feel better about it. Imagine a piece about the size of a dime (which constitutes most of the tip of your finger, really) and about the thickness of two quarters. Now imagine it connected by a tiny piece of skin. Now imagine it NO LONGER connected by that tiny piece of skin. Imagine it instead stuck to the inside of a bloody bandage, a small not-bloody circle in the middle of a brownish-red tragedy.

And if you're REALLY into detail, also imagine taking your killer razor out of your bag to inexplicably use it against your own stubbly face, despite the fact that it has tasted human blood and may just want more more more. Upon examination, you find that it is surprisingly not at all bloody, because when you cut yourself, your "Ow ow, holy shit, ow motherfucker OW!" reflex kicked in quickly enough to get you to the sink before any real bleeding began. What you do find is what appears to be a small piece of clear plastic stuck in the blades. But when you fish it out, you remember that most clear plastic doesn't have little fingerprint ridges in it. Then you sit down again. And maybe not eat for the rest of the day.

Apparently I cut it twice. One was the big cut, and one was a little bit shaved off the tip, waiting for me to discover it later.

So yeah. I cut off the end of my finger.

Now, I didn't cut off a major, life-changing chunk of my finger. I'll have a flat spot, that's certain, but I can still count to ten and Schuyler can still paint all my fingernails. Still, the cut went deep into that part of the skin where the nerves live, and they do not like being exposed like that. Two weeks after the cut, it is healing up nicely (amazingly, no infection, which goes to show that God really does protect children and stupid people), but you know what?

It still hurts. A lot.

It looks sort of cool, though. I'll leave that to your imagination.

February 20, 2009

Monster Slayers by the Bay

When you're a special needs parent, a Shepherd of the Broken, and you finally find a school that seems to get your kid and is truly working for a greater good, it's so easy to feel like you're living a world apart. It seems fragile, as if the bubble in which you exist is the only one of its kind in the world, and that if it should pop, everything would be entirely and devastatingly lost.

And then you find other bubbles, other pockets where people are building their own similar worlds, and suddenly it feels like everything might just be okay, and that the world might just be getting incrementally better, despite all appearances to the contrary. The broken are being helped to their feet and into the world all over, it turns out, and while the lost still vastly outweigh the found, it's a start. It won't do forever, or even for long, but it'll do for now.

Last week, my friend Monique van den Berg and I were fortunate enough, thanks to the efforts of the Prentke Romich Company and particularly due to the work of PRC's Kara Bidstrup, to visit two programs in the San Francisco Bay Area that are not only doing the same kind of work as Schuyler's AAC program here in Plano, Texas, but have served as models for this program and many others. We met other teachers, ones who have been doing this work with kids, REAL kids in REAL schools, and pretty much for as long as the technology has been in development to do so.

Most of all, I met the kids.

The Bridge School in Hillsborough, California was founded in 1986. The idea was to create a learning environment where kids with complex communication needs could develop and thrive all the way to adulthood, largely through the application of augmentative and alternative communication. The school uses a multi-modal approach, similar to how Schuyler communicates through a combinations of her device, her sign language and her limited verbal skills.

Since the very beginning , the school has been funded at least in part thanks to the annual Bridge School Benefit Concert, thrown every fall by Neil Young and his friends. The lineup over the years has been pretty impressive, including (and I'm not even kidding here) Bruce Springsteen, Billy Idol, Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia & Bob Weir, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, Tracy Chapman, Elvis Costello, Willie Nelson, Elton John, James Taylor, Simon & Garfunkel, Beck, Emmylou Harris, The Pretenders, David Bowie, The Smashing Pumpkins, Alanis Morissette, Dave Matthews Band, R.E.M., Sarah McLachlan, Barenaked Ladies, Eels, Sheryl Crow, Green Day, Lucinda Williams, Robin Williams, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Foo Fighters, Thom Yorke, LeAnn Rimes, Jack Johnson, Wilco, Counting Crows, Paul McCartney, Tony Bennett, John Mellencamp, Los Lobos, Norah Jones, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bright Eyes, Good Charlotte, Trent Reznor, Death Cab for Cutie, Gillian Welch, Devendra Banhart, Tom Waits with Kronos Quartet, John Mayer, Regina Spektor, Cat Power...

So yeah. The concert is a big deal. The bigger deal is what you find inside the school.

We met with the Bridge School's executive director, Dr. Vicki Casella, who was kind enough to take some time to explain the program, and then we were given a tour by Kristen Gray, the school's Outreach Program Manager. The Bridge School keeps a small student population, only fourteen kids at a time, but the program is a transitional one, with the goal of getting these kids back out into their community schools. The school supports about fifty kids outside of its small campus, and the logistics and resources and above all training required to do so must be daunting.

When I met the kids, I was suddenly aware of just how challenging a task this is for the Bridge School. Of the fourteen kids in the program, none were ambulatory and most presented physical challenges that could best be described as extreme. These are the cases that the Bridge School serves exclusively now. And yet every single one of them is learning to communicate, through a variety of creative techniques and strategies, all with the goal of graduating these kids from Bridge and transitioning them to their home school districts or other educational placements.

More similar to Schuyler's AAC classroom was our next destination. The TACLE program at Oakland's Redwood Heights Elementary is a program that was originally established in 1990 by the Bridge School, along with Oakland's Programs for Exceptional Children, California Children Services and Associates of Augmentative Communication and Technology Services. If the Bridge School is an island of specialized learning, then the TACLE program is an outpost, a fortress deep within neurotypical territory. Like Schuyler's class, these kids are integrated into the elementary school where they are housed. The teachers in the class, Stephanie Taymuree and Michele Caputo, were simply extraordinary. I'm not sure how to describe it except that the just GOT these kids. They understood exactly what the kids needed, they knew when to be calm and when to be excited, when to be "appropriate" and when to recognize the importance of a communication moment above all else. I found myself asking them questions about my own parenting approaches, questions I'd been carrying around for me for years without even realizing it.

Their skill and their commitment showed. It was clear in the enthusiasm of their students, many of whom lined up with their PRC Vantage speech devices to tell us the things that were fluttering in their heads like bats searching for a portal, looking to set those thoughts free. They used their devices to speak, sometimes in sentences and sometimes simply in excited, frantic strings of associated words, and despite the fact that many of them never even take their AAC devices home (due to occasionally difficult family lives at home), these kids were incredibly fired up about communicating electronically, to a degree that I'm embarrassed to say that I've not seen in Schuyler, perhaps ever.

By the end of the day, it had become clear to me that the teachers and therapists at Bridge and at the TACLE program are achieving their goals with persistence and patience and an overwhelming positivity. As I was introduced to these students, what I noticed most of all was the thing I always look for when I meet kids with disabilities. Regardless of their often extreme impairment or their difficult home situations, these kids are bright-eyed and forward leaning, excited about their surroundings and eager to break through or go around the walls that they've so often in the past found looming in their way.

If you've had any experience with good special education programs, you probably understand what I mean, just as any past exposure to a BAD program will have familiarized you with the dull-eyed, lethargic kids that populate those programs where teachers and therapists have, on some fundamental level, given up on their students and lost their faith. It's a kind of difference in a child's eyes and in their expressions; you see it in kids who are powerfully motivated and inspired rather than placated and underestimated and ultimately abandoned by their schools.

It's hard to describe, but I saw it in the eyes of the very first girl I met at Bridge. I guess the best way I can put it is that when I looked into her face and into those flashing eyes, behind the impairment and the physical manifestations of her own particular monster, I could see, with a sad and yet wonderful clarity, the little girl she was meant to be. You look into their eyes and you see them as they should have been, and as who they can be still in their own way. It's sad and it's wonderful, and I think perhaps most of all it's the thing that keeps these remarkable teachers and therapists coming back to work every day.

I understand how lucky we are. I know how fortunate Schuyler is, to be ambulatory and relatively unmarked by her monster in any significant physical way. She's nine years old now, and she's been in an excellent program for three and a half years. Schuyler finds a way to communicate now, and she may be delayed developmentally but it no longer feels like she's doomed to remain that way forever. Schuyler grows more "normal", for lack of a better word, every day, and one day she just might reach the point where she can walk, and more importantly TALK, in the neurotypical world like just about any other young woman you might meet. In some ways, she already does.

But after spending time with these kids and watching how hard they work with AAC technology to reach the world around them and communicate the things going on inside their beautiful and remarkable brains, I am reminded once again of a simple truth, one that I sometimes forget, to my shame.

Without the support of so many people and without the hard work of everyone who loves her and refuses to give up or accept things that no parent should ever accept, and most of all without her Big Box of Words and her little mental toolbox of sign language and her broken but earnest verbal expression, Schuyler Noelle would still be that ethereal, otherworldly little girl, the one I described in my book. So strange and beautiful, but not entirely ours or entirely in our world.

And then you find other bubbles, other pockets where people are building their own similar worlds, and suddenly it feels like everything might just be okay, and that the world might just be getting incrementally better, despite all appearances to the contrary. The broken are being helped to their feet and into the world all over, it turns out, and while the lost still vastly outweigh the found, it's a start. It won't do forever, or even for long, but it'll do for now.

Last week, my friend Monique van den Berg and I were fortunate enough, thanks to the efforts of the Prentke Romich Company and particularly due to the work of PRC's Kara Bidstrup, to visit two programs in the San Francisco Bay Area that are not only doing the same kind of work as Schuyler's AAC program here in Plano, Texas, but have served as models for this program and many others. We met other teachers, ones who have been doing this work with kids, REAL kids in REAL schools, and pretty much for as long as the technology has been in development to do so.

Most of all, I met the kids.

The Bridge School in Hillsborough, California was founded in 1986. The idea was to create a learning environment where kids with complex communication needs could develop and thrive all the way to adulthood, largely through the application of augmentative and alternative communication. The school uses a multi-modal approach, similar to how Schuyler communicates through a combinations of her device, her sign language and her limited verbal skills.

Since the very beginning , the school has been funded at least in part thanks to the annual Bridge School Benefit Concert, thrown every fall by Neil Young and his friends. The lineup over the years has been pretty impressive, including (and I'm not even kidding here) Bruce Springsteen, Billy Idol, Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia & Bob Weir, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, Tracy Chapman, Elvis Costello, Willie Nelson, Elton John, James Taylor, Simon & Garfunkel, Beck, Emmylou Harris, The Pretenders, David Bowie, The Smashing Pumpkins, Alanis Morissette, Dave Matthews Band, R.E.M., Sarah McLachlan, Barenaked Ladies, Eels, Sheryl Crow, Green Day, Lucinda Williams, Robin Williams, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Foo Fighters, Thom Yorke, LeAnn Rimes, Jack Johnson, Wilco, Counting Crows, Paul McCartney, Tony Bennett, John Mellencamp, Los Lobos, Norah Jones, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bright Eyes, Good Charlotte, Trent Reznor, Death Cab for Cutie, Gillian Welch, Devendra Banhart, Tom Waits with Kronos Quartet, John Mayer, Regina Spektor, Cat Power...

So yeah. The concert is a big deal. The bigger deal is what you find inside the school.

We met with the Bridge School's executive director, Dr. Vicki Casella, who was kind enough to take some time to explain the program, and then we were given a tour by Kristen Gray, the school's Outreach Program Manager. The Bridge School keeps a small student population, only fourteen kids at a time, but the program is a transitional one, with the goal of getting these kids back out into their community schools. The school supports about fifty kids outside of its small campus, and the logistics and resources and above all training required to do so must be daunting.

When I met the kids, I was suddenly aware of just how challenging a task this is for the Bridge School. Of the fourteen kids in the program, none were ambulatory and most presented physical challenges that could best be described as extreme. These are the cases that the Bridge School serves exclusively now. And yet every single one of them is learning to communicate, through a variety of creative techniques and strategies, all with the goal of graduating these kids from Bridge and transitioning them to their home school districts or other educational placements.

More similar to Schuyler's AAC classroom was our next destination. The TACLE program at Oakland's Redwood Heights Elementary is a program that was originally established in 1990 by the Bridge School, along with Oakland's Programs for Exceptional Children, California Children Services and Associates of Augmentative Communication and Technology Services. If the Bridge School is an island of specialized learning, then the TACLE program is an outpost, a fortress deep within neurotypical territory. Like Schuyler's class, these kids are integrated into the elementary school where they are housed. The teachers in the class, Stephanie Taymuree and Michele Caputo, were simply extraordinary. I'm not sure how to describe it except that the just GOT these kids. They understood exactly what the kids needed, they knew when to be calm and when to be excited, when to be "appropriate" and when to recognize the importance of a communication moment above all else. I found myself asking them questions about my own parenting approaches, questions I'd been carrying around for me for years without even realizing it.

Their skill and their commitment showed. It was clear in the enthusiasm of their students, many of whom lined up with their PRC Vantage speech devices to tell us the things that were fluttering in their heads like bats searching for a portal, looking to set those thoughts free. They used their devices to speak, sometimes in sentences and sometimes simply in excited, frantic strings of associated words, and despite the fact that many of them never even take their AAC devices home (due to occasionally difficult family lives at home), these kids were incredibly fired up about communicating electronically, to a degree that I'm embarrassed to say that I've not seen in Schuyler, perhaps ever.

By the end of the day, it had become clear to me that the teachers and therapists at Bridge and at the TACLE program are achieving their goals with persistence and patience and an overwhelming positivity. As I was introduced to these students, what I noticed most of all was the thing I always look for when I meet kids with disabilities. Regardless of their often extreme impairment or their difficult home situations, these kids are bright-eyed and forward leaning, excited about their surroundings and eager to break through or go around the walls that they've so often in the past found looming in their way.

If you've had any experience with good special education programs, you probably understand what I mean, just as any past exposure to a BAD program will have familiarized you with the dull-eyed, lethargic kids that populate those programs where teachers and therapists have, on some fundamental level, given up on their students and lost their faith. It's a kind of difference in a child's eyes and in their expressions; you see it in kids who are powerfully motivated and inspired rather than placated and underestimated and ultimately abandoned by their schools.

It's hard to describe, but I saw it in the eyes of the very first girl I met at Bridge. I guess the best way I can put it is that when I looked into her face and into those flashing eyes, behind the impairment and the physical manifestations of her own particular monster, I could see, with a sad and yet wonderful clarity, the little girl she was meant to be. You look into their eyes and you see them as they should have been, and as who they can be still in their own way. It's sad and it's wonderful, and I think perhaps most of all it's the thing that keeps these remarkable teachers and therapists coming back to work every day.

I understand how lucky we are. I know how fortunate Schuyler is, to be ambulatory and relatively unmarked by her monster in any significant physical way. She's nine years old now, and she's been in an excellent program for three and a half years. Schuyler finds a way to communicate now, and she may be delayed developmentally but it no longer feels like she's doomed to remain that way forever. Schuyler grows more "normal", for lack of a better word, every day, and one day she just might reach the point where she can walk, and more importantly TALK, in the neurotypical world like just about any other young woman you might meet. In some ways, she already does.

But after spending time with these kids and watching how hard they work with AAC technology to reach the world around them and communicate the things going on inside their beautiful and remarkable brains, I am reminded once again of a simple truth, one that I sometimes forget, to my shame.

Without the support of so many people and without the hard work of everyone who loves her and refuses to give up or accept things that no parent should ever accept, and most of all without her Big Box of Words and her little mental toolbox of sign language and her broken but earnest verbal expression, Schuyler Noelle would still be that ethereal, otherworldly little girl, the one I described in my book. So strange and beautiful, but not entirely ours or entirely in our world.

Stop looking at my hair like that. Just stop.

My friend and fellow fancy pants author Karen Harrington and I presented a panel for the Writers' Guild of Texas earlier this week, called "A Year in the Life of Two Debut Authors", and Karen has done a good write-up on her blog of some of the topics we touched on, in an entry called "8 Tips for The Debut Author".

Clearly, Tip #9 should be "Have someone look at your hair before you go out in public". Well, what are you going to do? Karen is always so pretty and put together and organized, and I am just a big mess all the time. She's nowhere near as compelling of a cautionary tale as I am, though. So, you know, I've got that going for me.

I am working on a few entries about my trip to San Francisco. They should be posted at some point between today and the cooling of the sun and the subsequent end of civilization as we know it.

Clearly, Tip #9 should be "Have someone look at your hair before you go out in public". Well, what are you going to do? Karen is always so pretty and put together and organized, and I am just a big mess all the time. She's nowhere near as compelling of a cautionary tale as I am, though. So, you know, I've got that going for me.

I am working on a few entries about my trip to San Francisco. They should be posted at some point between today and the cooling of the sun and the subsequent end of civilization as we know it.

February 17, 2009

Letter to PRC

I'm writing more about my visit to the Bay Area (much more, in fact), but I wanted to share a letter I just sent to the president and to the marketing director of the Prentke Romich Company, known to monster fighters all as the makers of Schuyler's Big Box of Words.

Sometimes I feel like so much focus falls on people when they don't measure up to expectations, and yet there are so many people out there getting it right. I don't ever want to forget to say thanks when they do.

Hello again!

I just wanted to take a moment and let you know that I had a very successful visit to the San Francisco area this past week, visiting the Bridge School and the TACLE Program at Redwood Heights Elementary School in Oakland. It was amazing to see how these programs work, and to meet the dedicated people who are fighting the good fight. It's one thing to talk about how augmentative communication technology SHOULD be implemented in a school environment, but quite another to see how people are making it a reality. It has given me a lot to think about, and to write about as well.

I would be remiss if I didn't let you know just how extraordinary Kara Bidstrup was in making my trip such a memorable experience. From the very beginning, she was enthusiastic and very efficient in setting up these visits and getting me where I needed to be without any trouble at all. She was very warm and friendly, and was a real pleasure to be around. It was clear that the people we met at both schools held Kara in high regard, and I can't imagine that she could have represented PRC with any higher degree of professionalism and enthusiasm.

Beyond her role in facilitating my school visits, Kara was a real joy to talk to one-on-one. I was especially thrilled when she came to my book signing the next night at Book Passage in Corte Madera. Schuyler and Julie were unable to come on this trip with me, but they appeared at the event via teleconferencing. When Schuyler used her Vantage on the screen and audience members began asking questions, Kara stepped up and was able to show a Vantage Lite and demonstrate how it functioned. I received a number of very appreciative comments from people who had been curious about the device when they read about it in the book and loved being able to see one in person, as well as having a knowledgeable person on-hand to answer questions about it. It made me realize that I should have invited a PRC rep to be on-hand at my solo events all along.

The longer I work with your company, both in my capacity as a writer and advocate and more importantly as Schuyler's father, the more impressed I am with the level of competence and enthusiasm of everyone who works for you. It speaks volumes about PRC that I was thrilled at how amazing Kara was, but not one bit surprised. Thank you once again for everything you've done, both for me and my family and for all the other people out there who seek so desperately for a voice and find one, thanks to you.

My continued best wishes,

Rob R-H

Sometimes I feel like so much focus falls on people when they don't measure up to expectations, and yet there are so many people out there getting it right. I don't ever want to forget to say thanks when they do.

Hello again!

I just wanted to take a moment and let you know that I had a very successful visit to the San Francisco area this past week, visiting the Bridge School and the TACLE Program at Redwood Heights Elementary School in Oakland. It was amazing to see how these programs work, and to meet the dedicated people who are fighting the good fight. It's one thing to talk about how augmentative communication technology SHOULD be implemented in a school environment, but quite another to see how people are making it a reality. It has given me a lot to think about, and to write about as well.

I would be remiss if I didn't let you know just how extraordinary Kara Bidstrup was in making my trip such a memorable experience. From the very beginning, she was enthusiastic and very efficient in setting up these visits and getting me where I needed to be without any trouble at all. She was very warm and friendly, and was a real pleasure to be around. It was clear that the people we met at both schools held Kara in high regard, and I can't imagine that she could have represented PRC with any higher degree of professionalism and enthusiasm.

Beyond her role in facilitating my school visits, Kara was a real joy to talk to one-on-one. I was especially thrilled when she came to my book signing the next night at Book Passage in Corte Madera. Schuyler and Julie were unable to come on this trip with me, but they appeared at the event via teleconferencing. When Schuyler used her Vantage on the screen and audience members began asking questions, Kara stepped up and was able to show a Vantage Lite and demonstrate how it functioned. I received a number of very appreciative comments from people who had been curious about the device when they read about it in the book and loved being able to see one in person, as well as having a knowledgeable person on-hand to answer questions about it. It made me realize that I should have invited a PRC rep to be on-hand at my solo events all along.

The longer I work with your company, both in my capacity as a writer and advocate and more importantly as Schuyler's father, the more impressed I am with the level of competence and enthusiasm of everyone who works for you. It speaks volumes about PRC that I was thrilled at how amazing Kara was, but not one bit surprised. Thank you once again for everything you've done, both for me and my family and for all the other people out there who seek so desperately for a voice and find one, thanks to you.

My continued best wishes,

Rob R-H

February 13, 2009

I am your San Francisco treat, baby

If you're in the Bay Area, this is your reminder to come see me tonight at 7:00, at Book Passage in Corte Madera. I think it's going to be a lot of fun. There may be some special surprises of the snack variety and just maybe, if I can figure out how to make it work, a special guest appearance of sorts. Oo, a teaser.

I'm having an amazing time in San Francisco. I spoke to an advanced composition class at the College of San Mateo, and afterwards we workshopped some of their own personal narrative pieces, all of which were really very good. I hereby repudiate all my cracks about "kids these days". I also visited the Bridge School and a program very similar to Schuyler's in Oakland, and it was an experience that I am still processing and will write about at length soon. Today I'm going to explore the city with Monique, and I'd be a terrible father to Schuyler if my day didn't include a visit to the Pirate Supply Store.

Oh, and I accidentally cut off the tip of my finger. I suppose I'll write about that soon, too.

I'm having an amazing time in San Francisco. I spoke to an advanced composition class at the College of San Mateo, and afterwards we workshopped some of their own personal narrative pieces, all of which were really very good. I hereby repudiate all my cracks about "kids these days". I also visited the Bridge School and a program very similar to Schuyler's in Oakland, and it was an experience that I am still processing and will write about at length soon. Today I'm going to explore the city with Monique, and I'd be a terrible father to Schuyler if my day didn't include a visit to the Pirate Supply Store.

Oh, and I accidentally cut off the tip of my finger. I suppose I'll write about that soon, too.

February 8, 2009

Muted anxiety

Recently, I've been reading a great deal of literature and material on the subject of special needs parenting (including an absolutely amazing manuscript I may be blurbing that I can't WAIT to tell you about in the coming months as it gets closer to publication), and the thing that strikes me once again is the incredible diversity of the experiences we have.

Recently, I've been reading a great deal of literature and material on the subject of special needs parenting (including an absolutely amazing manuscript I may be blurbing that I can't WAIT to tell you about in the coming months as it gets closer to publication), and the thing that strikes me once again is the incredible diversity of the experiences we have.In the past, I've addressed how those of us writing about our experiences as "Shepherds of the Broken" do so with a variety of perspectives and approaches to what our kids face. Some of us are pragmatists, some infuse our writing with spirituality or religion, some of us use humor, some report from a place of despair, and others write with cheerful optimism. One of the reasons I have largely rejected the idea of People First Language is that it only really works as intended when it's applied as a universal standard, which assumes that there is a common attitude and approach to special needs parenting. In my experience, nothing could be further from the truth.

Lately I've been especially aware of how the experiences we face as special needs parents are so wildly divergent as to seriously challenge the notion that we really even have a comparable perspective at all. We do, of course; the challenges we face in receiving services, the grief over the loss of the imaginary child bourn from our expectations who is not to be, the fight that we take on because if not us, then who? -- these really do seem to be universal experiences. But our kids all have individual monsters, with wildly different effects on their hosts. The variety of disabilities can be daunting when take a step back and take it all in. God, the Universe, Fate, whatever you believe in -- someone or something seems to have a limitless (and limitlessly cruel) imagination when it comes to ways to break children.

Among children with disabilities, Schuyler is luckier than most, we are aware of this. When people meet Schuyler, they tend to take her at face value; her monster is hidden, for the most part, and doesn't obviously stamp itself on her outward appearance. Her facial structure is "normal" (whatever that means), her social behavior is largely consistent with that of a neurotypical kid her age, and she is completely ambulatory, albeit somewhat clumsy. Truthfully, however, Schuyler tends to skew a little younger when she finds random play friends; her delay and her lack of language still makes her a more ideal playmate for kids who are a few years younger than she is. There are concepts that she simply doesn't get, concepts that a nine year-old should understand. It's nice to pretend that she's on track with other kids her age just because she's attending age-appropriate mainstream classes part of the day, but the truth is more complicated than that, and it's going to become more and more of an issue as she gets older. Will she ever catch up to her peers? Nobody knows, but she's not there yet, not by a long shot.

Still, it's easy to put her monster out of mind. This might be a strange confession from someone whose very identity as a writer and public speaker is largely defined by special needs parenting, but I don't think of Schuyler as a child with a disability, not most of the time. It's not that I forget, exactly. Rather, the accommodations and adjustments that we make as her parents when we communicate or interact with her on a daily basis have become ingrained in our natural behaviors. It's simply how it is with Schuyler.

When your child says something to you, do you automatically repeat it back to her to make sure she said what you think you heard? Do you keep an expensive electronic device within arm's reach at all times for the times that sign language and Martian fail to communicate a concept? We do, and the odd thing is, we do so without thinking about it most of the time. We've accepted the weird as our new normal, and honestly, your normal strikes us a a little weird. Normal conversation with a child? What kind of futuristic, science fiction concept is that? Do you have a talking cat, too? That's just crazy talk, man.

There are times when it all breaks down, though. Schuyler is a willful child, and while her school is, in most respects, the very best place in the world for her, she's still a square peg sometimes. This has very little to do with her monster and almost everything to do with her father, I know. Schuyler has a natural distrust for authority and a taste for random acts of meaningless defiance, personality traits that are nothing like Julie and everything like me. Notes come home from school reporting various acts of mild insurrection about once a week or so. "Schuyler refused to use a pencil today" was the most recent, and when asked why, she simply stated that she wanted to use a pen, as if the issue was obvious. She clearly understands the idea of her teachers as authority figures. I just don't believe she accepts it, not entirely.

I recognize this as a strength as well as a liability; it's a trait that is going to serve her well when she's older. But it presents a challenge and requires a delicate balance. The issue becomes more complicated when she disobeys Julie and me, of course. Schuyler defies us, because she's nine and because she's Schuyler, and we push back, because we'd like to avoid raising a feral anarchist if we can.

But when she gets in trouble, Schuyler shuts down. She freezes up when we insist that she use her device to explain herself; it's suddenly as if she has never used it before in her life. I mean it, too; she actually used it more proficiently back when she really had never used it before in her life. The problem goes beyond stubbornness, too. She seems to legitimately be unable to calm herself to the point that she can construct a dialogue. Instead, she tries to defend herself verbally, but the more upset she gets, she more unintelligible she becomes. Her words, already identifiable mostly through context and inflection alone, run together into an fretful, angry stream of sound. Her meaning disappears, replaced by an incomprehensible anxiety.

These are the worst moments for us, and while they don't compare to the worst moments some families face, they nevertheless involve a near-complete shutdown of communication. In those moments, our frustration and being unable to simply parent our child is exceeded only by Schuyler's frustration at suddenly finding herself under a baffling glass dome, shouting into a void. In those moments, we all feel broken.

I don't know what the answer is. It saps our strength, all of us, because it shines a hard light on one of the lingering deficiencies of Schuyler's use of the Big Box of Words. It illustrates just how far we all have to go, and how hard we have to work, in order to make this unnatural form of communication feel like second nature to her.

Most of the time, Schuyler doesn't seem broken, not to those of us who love her and live every minute in her world. Even now, though, after all these years and as far as we've come with her, it is painful and shocking when the monster bites.

February 4, 2009

Minnesota Parent review

"Fully formed: a father's journey with his nonverbal daughter"

by Beth Hawkins

Minnesota Parent: "Shelf Life", February 2009

Minnesota Parent: "Shelf Life", February 2009

"Somewhere in the process of advocating for his daughter's undaunted spirit, Robert comes to believe in himself as a father. Schuyler's Monster paints a haunting picture of the soul's need to be known, as well as the painful way in which becoming a parent forces one to recognize one's weaknesses and limitations."

by Beth Hawkins

Minnesota Parent: "Shelf Life", February 2009

Minnesota Parent: "Shelf Life", February 2009"Somewhere in the process of advocating for his daughter's undaunted spirit, Robert comes to believe in himself as a father. Schuyler's Monster paints a haunting picture of the soul's need to be known, as well as the painful way in which becoming a parent forces one to recognize one's weaknesses and limitations."

February 2, 2009

February 1, 2009

In which the author clarifies an important item.

From the comments to my last post:

From the comments to my last post:(After a six paragraph rant about the eeeevils of Socialism)

If Rob was a true socialist as he says he is, he does say he has a socialist heart. So I feel safe in making that assumption.

So Rob, will you keep the profits that you have earned in an honorable fashion from the sale of the book or hand them over to the state? Do you really have a socialist heart or are you just playing make-believe?

That's a fabulous question, thanks for asking! Here's the scoop!

No, I am not a Socialist, or a Marxist, or a Communist. (Is anyone anymore, really? Outside of places like South America or Albania?) What is perhaps confusing you in this instance is my use of Humor. In the past, I've been called a Socialist by conservative readers for a number of progressive positions I've taken. The most notable instance occurred when I argued in an admittedly ill-considered guest post on PajamasMedia that kids with special needs deserve an equal education and at least the option of a mainstream education in the public schools for which we all pay with our taxes.

The accusation was so funny to me that I began to sarcastically refer to myself as a Socialist, the humor (at least to me) originating in the idea that I was somehow a bad American, a Socialist and (best of all) an elitist because my political and social beliefs differed from theirs.

It was, in other words, a Joke.

The term "joke" is defined by Wikipedia as "a short story or ironic depiction of a situation communicated with the intent of being humorous". The definition goes on to set out the antiquity, anthropology and psychology of these jokes and even outlining the rules that govern them and the different types of jokes that can typically be found.

Whew! That's complicated!

I realize now how confusing my use of these so-called Jokes can be, so I've decided to explain a few more of them, ones that I know I've used in the past.

OTHER JOKES THAT I HAVE MADE THAT DO NOT ACTUALLY REFLECT THE TRUTH:

- Although she communicates using an electronic device and a synthetic voice, Schuyler is not actually a cyborg. She is not half human, half robot. In fact, the percentage of Schuyler's body that consists of any robotics whatsoever is exactly zero.

- Furthermore, Schuyler does not actually speak Martian.

- In fact, to the best of my knowledge or that of the scientific community at large, there is no such language as Martian. (Note: This could be disproven at a later date.)

- I did actually purchase new pants shortly before my book was published, after I forgot to pack mine when I took Schuyler to New York City to meet with my publisher. The pants I purchased, however, were in no way actually Fancy Pants, aside from coming from the Gap in Times Square and being priced accordingly. In reality, I do not own a pair of so-called "Fancy Pants", and I do not believe that I am actually a Fancy Pants Author, not even by virtue of metaphorical Fancy Pants, or some sort of "Fancy Pants of the Mind".

- I do not own a Cloak of Invisibility, nor do I believe people who ignore me in public places such as the mall or the Department of Motor Vehicles do so because I am actually invisible. I will not, therefore, don this Cloak of Invisibility in order to fight crime.

- When a car or truck on the highway in front of me drifts across the lanes with abandon, I do not in fact believe that the driver of said vehicle is the Flying Dutchman, doomed to wander the roads for all eternity.

- I do not actually believe that my car, Atomo, is "the Air-conditioned Hellcar of the Apocalypse", and I have no plans to drive it across a barren wasteland, Mad Max-style, following the inevitable collapse of our civilization.

- I also do not believe that my previous car, a VW Beetle known as "Beelzebug", was really the Devil or was in any way affiliated with Satan or any supernatural being associated with darkness or evil. (Note: The Volkswagen Corporation doesn't count, as they are not, by definition, a supernatural entity.)

- I do not actually believe that Christianity is a zombie cult, or that Jesus is an Imaginary Friend. (Note: Actually, I kind of do. I'm sorry.)

- Although I claim to quote from its pages from time to time, I do not believe there is actually a publication called The Journal of No Shit.

- In reality, I do not believe that the term "differently abled" refers to children with superhero talents such as the ability to fly.

- Although I publicly claimed otherwise, I would not have actually voted for John McCain in the last presidential election if he had used the words "dagnabbit", "new-fangled" or "old-timey" in any of the debates.

- I did not really believe that the tornado sirens in Collin County, Texas would go off as soon as the voting machine registered my vote for Barack Obama.

- I do not believe that every conservative Republican is a humorless pinhead, and will continue to make that determination on a case-by-case basis.

I hope this clears up any confusion, and thanks for writing!

January 30, 2009

Promotion, sans apologies

I just wanted to post a reminder for those of you in the Bay Area, I will be appearing at Book Passage in Corte Madera, California on February 13th at 7pm. Come see Jimmy Carter the night before, and then just camp overnight. I'm sure they won't mind.