The IEP, or Individualized Education Program, is part of the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which we Shepherds of the Broken use, along with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), to bully the rest of the world into helping our kids get an appropriate education and generally not get swept under the rug. The IEP is the plan by which parents, teachers and therapists decide on the course of a student's school studies.

Here's what the government says about the IEP:

Each public school child who receives special education and related services must have an Individualized Education Program (IEP). Each IEP must be designed for one student and must be a truly individualized document. The IEP creates an opportunity for teachers, parents, school administrators, related services personnel, and students (when appropriate) to work together to improve educational results for children with disabilities. The IEP is the cornerstone of a quality education for each child with a disability.

To create an effective IEP, parents, teachers, other school staff -- and often the student -- must come together to look closely at the student's unique needs. These individuals pool knowledge, experience and commitment to design an educational program that will help the student be involved in, and progress in, the general curriculum. The IEP guides the delivery of special education supports and services for the student with a disability. Without a doubt, writing -- and implementing -- an effective IEP requires teamwork.

What that little block of government-issue cheese doesn't tell you is that for many parents of a broken kid, or perhaps even most parents, the IEP meeting itself is usually a gigantic, frustrating pain in the ass.

We've been lucky since coming to Plano. Our IEP meetings are generally a breeze now, although we certainly paid our dues back in Manor (the district near Austin where she attended school before) and in New Haven. I still remember the meeting where Schuyler's speech therapist in Manor finally admitted that the reason she wasn't recommending sign language was that she didn't know it herself and didn't think she had time to take a class. That was swell.

The Plano public schools' special education programs are among the best in the country, and so for the first time we've been able to relax a little and allow her teachers to take the lead. You have no idea what a relief that is, unless you have a broken child yourself, in which case you know EXACTLY what I'm talking about. IDEA provides for something known in special needs circles as "FAPE", or Free Appropriate Public Education. It's the part of the law that sets the minimum standard for special education in public schools. In some cases it's a life saver; in others, a mockery.

(If you want to put your broken kid in a neurotypical private school, you're on your own. Private schools do not have to accept students with special needs, and many choose not to. The ones that do typically make the parents of the child responsible for the cost of additional resources. On the other hand, your broken child is free to talk about Jesus, so there you go.)

What FAPE doesn't guarantee is the best possible special education. It provides for an "appropriate education", which many courts have defined as "access to an education" or a "basic floor of educational opportunity". Parents who go to court seeking additional services for their kid are told never to use the terms "best" or "maximizing potential" during legal proceedings. Parents have to educate themselves on what their kids need, and they need to find the programs that serve their kids the best. The idea of moving to a whole new city in order to put Schuyler in a particular school district struck some parents as an extreme move on our part, but to other parents of a broken child, it made perfect sense.

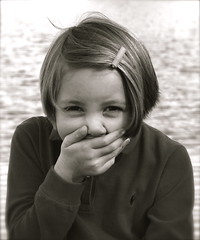

Plano was worth it, and continues to be worth it, but the thing is, it's not just because the teachers and specialists are good. Schuyler's team is exactly right for her for one simple reason. With a very few exceptions, they almost never tell us what she CAN'T do. They assume we already know that, and they're right. They set goals for Schuyler, they let us know when she's succeeding and when she's falling short, but they never set boundaries and they never accept limitations for her.

They get her. I suspect they get them all.

At her last meeting, her team pushed hard for a cognitive evaluation, a school-mandated three-year assessment of her abilities that we originally resisted when she was in Manor. I didn't trust her old school team in Manor, not with a test like that. Such a test is very difficult to administer to a non-verbal subject, and very subjective, so it requires an expert test administrator who can make appropriate accommodations for a nonverbal subject. This is the first time we've trusted the school to administer such a test correctly. Even so, I had and continue to have my reservations.

At the end, there's a number, and our fear was that it would be a number that would follow her along forever. Schuyler didn't do poorly on the test, but she had problems. I was happy to see that her team did recognize (in the actual written report itself) that her score probably represented the low end of her actual capabilities. It was nice to have confirmation that I'm not just being Defensive Denial Dad when I mention her aversion to evaluations. They see it, too. Schuyler can be defiant in evaluations, perhaps partly in sport but mostly because she becomes extremely impatient. She likes to give the answer after merely glancing at the possibilities, and the problem only gets worse as the test drags on. It's a problem that they identified at this last meeting, and one that we're going to have to work on.

The possibility was brought up that she might be ADD. Attention Deficit Disorder often accompanies cerebral palsy, which is related in many ways to Schuyler's polymicrogyria. Because of her malformed brain and the fact that no one knows exactly how it functions at the high level that it does, medications that affect brain chemistry are probably out of the question. But ADD was mentioned only as a possibility, and not one that they even feel compelled to test her for yet, so it's probably a little early to freak out. Even so, Julie and I were both surprisingly unmoved when they mentioned it.

With everything that our daughter has been through (and will likely go through in the future) with polymicrogyria, Attention Deficit Disorder isn't very scary. Compared to Schuyler's monster, it's a hamster.