We received results of Schuyler's ambulatory EEG tonight while we were driving to dinner. It's funny, but after everything we'd been through, all the anxiety and glue-headedness, I'd almost forgotten that we were waiting for a call back.

As I expected, the news was complicated. It's probably only in the movies that doctors deliver the "everything's okay!" or the "everyone's dooooomed!" speeches. Shades of grey, as I wrote before. But I think we're going to put this in the Good News column.

First and foremost, as in her initial EEG, Schuyler didn't have any seizures during the weekend of her ambulatory EEG, either. If she's having any at all, they are clearly infrequent enough not to pose a problem at this point. Her brain waves during her waking hours were pretty normal, in fact, which makes me think, with cautious optimism, that she's not having any absence seizures at all.

The grey shades come at night. When Schuyler sleeps, the left side of her brain experiences abnormal, unexplainable episodes that aren't seizures but are nevertheless troubling. They don't happen constantly and don't represent a consistent state of being, but they're there, and not random incidents but regularly occurring events. They only come when she sleeps, and they occur mostly on the left side.

Are they precursors to something more sinister down the road? Seizures yet to come? The vanguard of an alien invasion, foretold in Schuyler's strange Martian jabbering? Is this a harmless oddity of Schuyler's funky, broken brain or a Very Bad Thing? Is this a new phenomenon, or has it been there all along, just one more signature of Schuyler's monster? No one knows.

Anyway, there it is. No absence seizures, which is good, but some weird scary boo sleepytime thing that could be nothing at all or the beginning of seizures, stigmata and possibly the Apocalypse. I do believe we're going to celebrate the absence of monster who isn't here just yet, even if its plane has just been delayed, and not worry about the other thing for the time being.

In six months, we'll go through this all over again. Perhaps by then, Schuyler will have forgotten about the glue in her hair. That's not what the smart money says, though.

Schuyler is my weird and wonderful monster-slayer. Together we have many adventures.

January 19, 2009

Izzie Redux

It wasn't a huge surprise. She'd been slowing down a lot lately, which is probably why I was moved to write this post a couple of weeks ago. I didn't notice anything unusual when I gave my dwarf hamsters their favorite little yogurt treats yesterday; Isolde took hers from my hand and held it in her gimpy little paws, while Tristan took his and scurried suspiciously to the other end of the tank. Being unable to run, Izie had long ago decided to trust.

But when I checked on them this morning, I knew something was wrong. Tristan was up and moving around by himself, seeming a little out of sorts. But Izzie was nowhere to be found. I poked around in the bedding and found her curled up in the corner. She'd died in the night, apparently in her sleep.

Well, I'm a forty-one year-old, supposedly grown adult who probably shouldn't be overly sentimental about a hamster, but yeah, I'm pretty bummed. Izzie was a tough little critter, and her passing feels, I don't know, portentous.

More to the point, Schuyler likes to come and see the hamsters, mostly because she likes Izzie so much. Tristan is too twitchy and quick-footed for her, but Izzie would let Schuyler reach in and pet her and even hold her. As I said, when she lost her mobility, Izzie had long ago learned to trust the big hands.

When Schuyler woke up, I told her I had some bad news. I took her into our bedroom and showed her Tristan. She noticed immediately that he was alone; he was never without Izzie, not in the past year or so. I explained to her that Izzie had died in the night. Schuyler gave me a long hug, and for a moment I thought she might cry. But instead she just watched Tristan for a moment.

She looked up at me. "He's sad," she said, signing sad to me. "He needs a new friend."

So I suppose I know what we're doing today.

Goodbye, Izzie. For a tiny, broken rodent, you were weirdly inspiring.

But when I checked on them this morning, I knew something was wrong. Tristan was up and moving around by himself, seeming a little out of sorts. But Izzie was nowhere to be found. I poked around in the bedding and found her curled up in the corner. She'd died in the night, apparently in her sleep.

Well, I'm a forty-one year-old, supposedly grown adult who probably shouldn't be overly sentimental about a hamster, but yeah, I'm pretty bummed. Izzie was a tough little critter, and her passing feels, I don't know, portentous.

More to the point, Schuyler likes to come and see the hamsters, mostly because she likes Izzie so much. Tristan is too twitchy and quick-footed for her, but Izzie would let Schuyler reach in and pet her and even hold her. As I said, when she lost her mobility, Izzie had long ago learned to trust the big hands.

When Schuyler woke up, I told her I had some bad news. I took her into our bedroom and showed her Tristan. She noticed immediately that he was alone; he was never without Izzie, not in the past year or so. I explained to her that Izzie had died in the night. Schuyler gave me a long hug, and for a moment I thought she might cry. But instead she just watched Tristan for a moment.

She looked up at me. "He's sad," she said, signing sad to me. "He needs a new friend."

So I suppose I know what we're doing today.

Goodbye, Izzie. For a tiny, broken rodent, you were weirdly inspiring.

January 13, 2009

Fairy howl

January 12, 2009

Maya's Monster

Here's a story I happened across. On one hand, it's a fluffy, feel-good story about a little girl with a disability and her helpful hero dog.

But here's the thing. The little girl, Maya Pieters? She has bilateral perisylvian polymicrogyria, also known as congenital bilateral perisylvian syndrome.

Schuyler's monster.

Her BPP manifests itself very differently from Schuyler's. Unlike Schuyler, this little girl suffers from seizures, frequent and serious. Also unlike Schuyler, however, she speaks.

I don't really have much of a reason for posting this here, except that it occurred to me as I was watching the video that it was the first time I've ever watched video of (much less met in person) another child with BPP. How strange it was to hear her speak.

Also, Schuyler's dog, Max? Totally useless. Sorry, dude.

But here's the thing. The little girl, Maya Pieters? She has bilateral perisylvian polymicrogyria, also known as congenital bilateral perisylvian syndrome.

Schuyler's monster.

Her BPP manifests itself very differently from Schuyler's. Unlike Schuyler, this little girl suffers from seizures, frequent and serious. Also unlike Schuyler, however, she speaks.

I don't really have much of a reason for posting this here, except that it occurred to me as I was watching the video that it was the first time I've ever watched video of (much less met in person) another child with BPP. How strange it was to hear her speak.

Also, Schuyler's dog, Max? Totally useless. Sorry, dude.

'Thrown Away' Dog Saves Little Girl's Life

By Laurie LaMonica

December 30, 2008

LANCASTER COUNTY, Pa. -- When the Pieters family adopted Jack, a dog once left to die in a dumpster, they hoped he would act as a constant companion to their daughter, Maya.

They never considered that the Terrier mix would also save the little girl's life, on more than one occasion.

Jack's loyalty -- and keen senses -- have proved that one person's trash can truly become another's treasure.

Just ask 8-year-old Maya, who inspired her family's trip to the Humane League of Lancaster County in 2004. When the Pieters saw how seamlessly Maya bonded with Jack, he had nowhere to go but out of the kennel, and into their home.

"Maya was down on her knees and her face as close to the gate as can be and he's licking her and I heard Maya talk more then to him then she had in a whole week," recalled Maya's mother, Michelle Pieters, of their first encounter with the dog.

The connection was exceptional for the young girl, whose condition forces her to struggle with normal oral and social functions.

When Maya was 3-years-old she was diagnosed with congenital bilateral perisylvian syndrome, an extremely rare condition that only 100 to 200 people in the world are reported to have.

The disease affects Maya's oral motor functions -- such as speech and swallowing -- and could cause seizures. But it also took a toll on Maya's self esteem. Always left out by other children, Maya became very withdrawn at a young age.

Maya's speech therapist, Donna Buss, suggested the Pieters family get a dog in 2003. She thought it might benefit Maya's socialization skills. Buss says Maya's shyness made their sessions difficult -- at the time, very little progress was being made.

So the Pieters launched a search to adopt the perfect dog. It took one year to find one that Maya felt comfortable with -- but the wait, in the end, was all the more worthwhile.

Though flea infested and dirty, Jack was the miracle for which the Pieters were searching.

Maya bonded with Jack instantly and the connection would prove more significant than Maya or her parents could have ever predicted.

Jack was sleeping in his crate one morning last year, when suddenly, without apparent provocation, he leaped from his bed and darted up the steps to Maya's room. The door was closed, but Jack sensed that Maya was inside -- and that she, for whatever reason, needed help.

The dog began to relentlessly claw and bark at the door, until Maya's family took notice of the dog's frantic state.

Jack, the Pieters realized, knew exactly what he was doing. Maya was found in her room, having her first seizure in her sleep.

Jack's urgent response to Maya's seizure probably saved her life, as the seizure was a new, unprecedented symptom of her condition.

The Pieters took to calling the little shelter dog "Maya's guardian angel."

Since that first episode, Maya has suffered other seizures. Each time, Jack has been able to preemptively sense when Maya is about to have a seizure. He has broken her fall, sat on top of her to help settle her convulsing body, and when she finally wakes up, licks her tears dry.

Jack has helped Maya in other ways as well. Upon adopting the dog, Maya's oral motor functions have improved drastically. Before Jack, Maya did not speak very often and was very sensitive to her face being touched.

Jack has helped Maya overcome these problems with routine face lickings, playtime and simply standing in as Maya's constant companion.

All of these accomplishments led to Jack's nomination for the Humane Society of the United State's "Valor Dog of the Year," an award to honor and celebrate dogs that have performed extraordinary acts of courage.

Jack competed against heroic dogs across the country, and although he didn't win the main prize, he was granted the "People's Choice" award.

Jack may have no idea he is nationally known for his good deeds. All he knows is someone once gave up on him, threw him away like a piece of trash.

And now, he is loved by a family, cherished by a little girl. In return, as much as Maya Pieters gave him a new chance at life, Jack has given her the same gift, as well.

Glue

Schuyler had a good weekend with her ambulatory EEG. She made the best of her cyborg status, even putting together a little headwear fashion show yesterday. She was a real trouper, and when we went to the neurologist's office this morning to have the gear removed, we though the worst was over.

Yeah. It turns out that the tape in her hair wasn't what actually secured the sensors in place. No, that would be the glue.

Glue.

After washing her hair for about an hour and using everything from clarifying shampoo to dishwashing soap, Schuyler still has a sticky, persistent mess in her hair, stuff that reminds me in its consistency of the glue we used to use to put together model airplanes when I was a kid. It's not coming out easily. A call to the unfriendly tech who put this crap in her hair in the first place was no help. ("Did you try running a comb through it?" Really? Really?) Helpful friends on Facebook and Twitter, many of whom have been through this themselves, have suggested conditioner, oil-based washes, fingernail polish remover, Goo Gone, peanut butter, rubbing alcohol, peppermint oil, vegetable oil, mineral oil, baby oil, tea tree oil and a concoction involving aspirin, shampoo and Seabreeze. All of which we'll no doubt end up trying before this is over.

I'm annoyed. I am, in fact, profoundly annoyed, because I cannot imagine that in the year 2009, the very best way to secure EEG leads to a child's head is with glue. (For that matter, is there really no other way to measure brain activity that this? Isn't this technology from the 1970s? Is my kid's brain activity being monitored by machinery that predates the 8 track player?) We're nearing the end of the first decade of the 21st Century, popularly known as The Future. Really? Fucking glue?

The answer, I suspect, is of course they could develop something better, something with a bond that could be easily broken with a specific chemical compound design especially for the purpose. I wouldn't be one bit surprised to find that just such product already exists.

But why bother? Those of us who have been immersed in medical procedures for years learned long ago that while there are a lot of very caring doctors out there, the medical industry as a whole still struggles with the concept of the patient as a human being. This is especially true of pediatrics, where psychological and social development is particularly vulnerable.

Schuyler had her ambulatory EEG performed by pediatric neurologists, after all. You might think that this meant they were especially sensitive to the issues involved with children, including the social and psychological effects of the treatment and studies being undertaken. But when no one sees a problem with putting glue, and lots of it, in the pretty hair of a nine year-old girl and then sending her back into an ugly world that's already not very nice to a kid who is different, that's because no one's considering the psychological and social issues that might come as a result. Not even "pediatric" neurologists.

It's not a huge issue, not in the big scheme of things. We'll get all this crap out of her hair somehow, and if we don't, it'll work its way out, or it'll grow out. The larger issue for me is that once again, we are witness to yet another example of how Schuyler and her fellow broken children are marginalized by the medical industry.

It's one of the reasons I do what I do, and write what I write. Because Schuyler is more than a transportation unit for a scientifically interesting brain, and she's more than a case study to which an insurance payment claim may be attached. She's wondrous little girl, and putting glue in her hair because it's the easiest way to accomplish your medical task diminishes you and your industry, not her.

So yeah. I'm pissed. She's not too pleased, either.

Update: We went the all-natural route, working in coconut oil and peanut butter and letting it sit for a couple of hours. She's in the bathtub now, and it seems to have mostly worked. Her head smells weird but appears to be glue-free. So now we know.

Yeah. It turns out that the tape in her hair wasn't what actually secured the sensors in place. No, that would be the glue.

Glue.

After washing her hair for about an hour and using everything from clarifying shampoo to dishwashing soap, Schuyler still has a sticky, persistent mess in her hair, stuff that reminds me in its consistency of the glue we used to use to put together model airplanes when I was a kid. It's not coming out easily. A call to the unfriendly tech who put this crap in her hair in the first place was no help. ("Did you try running a comb through it?" Really? Really?) Helpful friends on Facebook and Twitter, many of whom have been through this themselves, have suggested conditioner, oil-based washes, fingernail polish remover, Goo Gone, peanut butter, rubbing alcohol, peppermint oil, vegetable oil, mineral oil, baby oil, tea tree oil and a concoction involving aspirin, shampoo and Seabreeze. All of which we'll no doubt end up trying before this is over.

I'm annoyed. I am, in fact, profoundly annoyed, because I cannot imagine that in the year 2009, the very best way to secure EEG leads to a child's head is with glue. (For that matter, is there really no other way to measure brain activity that this? Isn't this technology from the 1970s? Is my kid's brain activity being monitored by machinery that predates the 8 track player?) We're nearing the end of the first decade of the 21st Century, popularly known as The Future. Really? Fucking glue?

The answer, I suspect, is of course they could develop something better, something with a bond that could be easily broken with a specific chemical compound design especially for the purpose. I wouldn't be one bit surprised to find that just such product already exists.

But why bother? Those of us who have been immersed in medical procedures for years learned long ago that while there are a lot of very caring doctors out there, the medical industry as a whole still struggles with the concept of the patient as a human being. This is especially true of pediatrics, where psychological and social development is particularly vulnerable.

Schuyler had her ambulatory EEG performed by pediatric neurologists, after all. You might think that this meant they were especially sensitive to the issues involved with children, including the social and psychological effects of the treatment and studies being undertaken. But when no one sees a problem with putting glue, and lots of it, in the pretty hair of a nine year-old girl and then sending her back into an ugly world that's already not very nice to a kid who is different, that's because no one's considering the psychological and social issues that might come as a result. Not even "pediatric" neurologists.

It's not a huge issue, not in the big scheme of things. We'll get all this crap out of her hair somehow, and if we don't, it'll work its way out, or it'll grow out. The larger issue for me is that once again, we are witness to yet another example of how Schuyler and her fellow broken children are marginalized by the medical industry.

It's one of the reasons I do what I do, and write what I write. Because Schuyler is more than a transportation unit for a scientifically interesting brain, and she's more than a case study to which an insurance payment claim may be attached. She's wondrous little girl, and putting glue in her hair because it's the easiest way to accomplish your medical task diminishes you and your industry, not her.

So yeah. I'm pissed. She's not too pleased, either.

8:15 pm

Update: We went the all-natural route, working in coconut oil and peanut butter and letting it sit for a couple of hours. She's in the bathtub now, and it seems to have mostly worked. Her head smells weird but appears to be glue-free. So now we know.

January 11, 2009

Hawaiian Rock Star Princess Knight Cyborg

January 9, 2009

January 6, 2009

One Week

So yes, let's take a look at this week, this one week in our lives here. I'd call it a roller coaster ride, if there existed a roller coaster that required both an oxygen tank for the highest altitude and a pressure suit for the subterranean low parts. Mostly, it's just a weird week.

Sunday. We started off the week with an all-nighter, in preparation for the Sleep Deprivation EEG the next day. Schuyler and I got through it with beverages, snacks, Cloverfield, Speed Racer and King Kong (the Schuyler "Good Parts" version, which basically skips the first hour, and includes the scary fish monster in the director's cut).

Monday. Well, you read about her EEG already. No seizures, but episodic abnormalities recorded. Neurologist said that he will schedule a new EEG, this one lasting 48 hours and requiring Schuyler to wear a mobile device for two days. After the unhappy ending of Monday's EEG, I'm not looking forward to telling her that she gets to do it again, and for, you know, forty-eight times as long. The doctor's office will call us to let us know when this new EEG will occur. If past experiences with neurologists are any indication, this appointment will be sometime in June.

Tuesday. Today, actually. The trade paperback edition of Schuyler's Monster came out. You went and bought a copy, plus two for your friends, right? No? Okay, well, here you go.

Wednesday. Who knows what tomorrow will bring?

Thursday. This is the day of my big author event at the Dallas area's extremely cool new independent bookstore, Legacy Books. (Beware, there's a loud thing on their website.) There's a wine bar, too. I'm just saying.

Which brings us to...

Friday. Turns out I was wrong about neurologists. When she gets out of school, Schuyler will be picked up by Julie, who will then take her to the neurologist to have her funky wire hat put in place for the weekend. I have no idea what it will look like, although I'm hoping it'll be something like this:

Schuyler will wear the funky wire hat until Monday, when I will take her back to have it removed from her no doubt slimy and vile little head. Then there'll be about fifty shampoos and as much ice cream as she can eat.

It was a delicate dance, telling Schuyler about her impending return to the EEG, which she ended up hating yesterday. She was resistant to the idea at first, but she responded very positively to that oldest parenting tool, the bribe. She says she's excited about it now, excited about proving that she can be a good girl, and a big girl, in order to claim her Prize. Her Bribery Prize.

Sometimes people ask me how I think Schuyler will react to the things I've written about her here and in the book. Perhaps I'm in denial, but I truly believe that she will read my words and know of my love for her above all else, and her grasp of the bond we share will only be strengthened by her understanding of how deeply that bond has run, her whole life. There is very little I have ever written about her that I think she might find upsetting.

But Schuyler, my love, my sweet darling girl, if you look back on this and read this entry from the vantage point of adulthood, I have a shameful confession to make. Do you remember the bribe I offered you in exchange for your cooperation in another pain in the ass EEG? The new Mac, your very first computer, the one I said I would buy for you when I got my next royalty check in February of this year, IF you complied with this new test?

Well, yeah. Funny thing. Turns out, I was already planning to get it for you anyway. Dick move on my part, I know.

January 5, 2009

Grey matters

We wanted a black and white answer, something sure, something where we could say "That's great news," or "That sucks, I'm going to get drunk". Something where our friends and family and readers could join us in celebration or console us as we got ready for the next big fight.

The reality that most special needs parents face is cloaked in shades of grey. We finally receive the answers for which we wait for so long, and we step back and look at them and say, "Huh. Okay then. What now?"

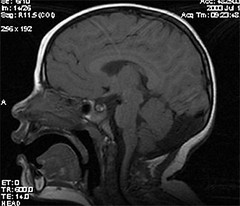

So here's the short version. During the hour or so that Schuyler was connected to the EEG monitor, no seizures were recorded. A number of episodic abnormalities were recorded, none of them bilateral and the majority of them occurring on the left side of her brain. Probably not surprising, considering the malformation of Schuyler's brain that is the signature of her monster, but it presents an unknown wrinkle nevertheless. These abnormal episodes aren't seizures. We're not sure what they are or what effect they have on her, if any.

More questions. More grey areas.

The next step will be an extended, 48-hour EEG, in which Schuyler will spend the weekend wearing a portable unit that will record her brain's electrical activity as she goes through her day. Not sure when this will happen, but we'll find out soon. Easy, right?

I'm not sure how it's going to work, actually. Getting her to go through another EEG might be a challenge. She was having a good time for the early part of the procedure. The tech was a lot of fun, and he let her help put the leads together with the tape and ask "What is this?" about every device and doodad he used. She loved that he could mysteriously understand every Martian word she said, as if he spends his days hearing worse speech than hers from more severely broken kids, which of course he does. She didn't even mind the stinky, sticky blue goo that went in her hair beneath the sensor contacts.

But when the test began in earnest and the lights began flashing, she suddenly began to take it seriously. I think she suddenly remembered, at least on some level, the endless tests and evaluations and medical procedures that predated her diagnosis back in 2003. By the time she woke up from the sleeping portion of the festivities and rubbed her little hands (and apparently just a little of the blue goo) in her eyes, she was well and truly DONE with the EEG. It has been years since I've seen her cry like that. She actually asked for Jasper, her oldest and most beloved teddy bear, and wouldn't let go of him for the rest of the afternoon.

I think I understand what she was feeling. Even though she was probably too young to remember much of it now, I think on some subconscious level, Schuyler was suddenly back in 2003 again, being tested and evaluated and confused by medical procedures which could not have possibly made any sense to her. For a while, Julie and I were in 2003 again. Not because of anything that was actually happening today, because really, the EEG was just about the least traumatic procedure imaginable. Nothing painful except for the irritation in her eyes (and really, that was just the blue icing on the already unhappy cake at that point), and no one was treating her like a patient instead of a person. And yet, the underlying feeling was the same.

Sometimes, most of the time, the monster isn't a thing we face. It's a thing we fear, a thing that exists not as a reality, which can be shitty but is at least something that can be grappled with, but instead as a growling "What If?" in the dark. When Julie saw Schuyler asleep on that bed, her head wrapped in wires and full of innocent little girl dreams, she cried, because that's how she purges it. She cries and then she gets back to work. I sat in a chair next to the bed, the lights turned down low as I watched my little girl sleep, and for a few minutes I let myself give in to the gathering gloom, the shadow that seems to creep around Schuyler in those moments. I didn't cry so much as let the feeling grip me. Tears in my eyes, perhaps, but not crying so much as feeling that little pit as it opened again, the one that we first saw six years ago and only occasionally have to peek into.

And then we pull ourselves together, we dispel the fears, if only for a little while, and when the lights come on, the shadows recede. And we get back to work.

We ask black and white questions, and we receive grey answers in return. And when I think about it, I guess that's probably for the best. I've seen far too many families who looked for black and white answers and only got black ones. I'll take grey.

The reality that most special needs parents face is cloaked in shades of grey. We finally receive the answers for which we wait for so long, and we step back and look at them and say, "Huh. Okay then. What now?"

So here's the short version. During the hour or so that Schuyler was connected to the EEG monitor, no seizures were recorded. A number of episodic abnormalities were recorded, none of them bilateral and the majority of them occurring on the left side of her brain. Probably not surprising, considering the malformation of Schuyler's brain that is the signature of her monster, but it presents an unknown wrinkle nevertheless. These abnormal episodes aren't seizures. We're not sure what they are or what effect they have on her, if any.

More questions. More grey areas.

The next step will be an extended, 48-hour EEG, in which Schuyler will spend the weekend wearing a portable unit that will record her brain's electrical activity as she goes through her day. Not sure when this will happen, but we'll find out soon. Easy, right?

I'm not sure how it's going to work, actually. Getting her to go through another EEG might be a challenge. She was having a good time for the early part of the procedure. The tech was a lot of fun, and he let her help put the leads together with the tape and ask "What is this?" about every device and doodad he used. She loved that he could mysteriously understand every Martian word she said, as if he spends his days hearing worse speech than hers from more severely broken kids, which of course he does. She didn't even mind the stinky, sticky blue goo that went in her hair beneath the sensor contacts.

But when the test began in earnest and the lights began flashing, she suddenly began to take it seriously. I think she suddenly remembered, at least on some level, the endless tests and evaluations and medical procedures that predated her diagnosis back in 2003. By the time she woke up from the sleeping portion of the festivities and rubbed her little hands (and apparently just a little of the blue goo) in her eyes, she was well and truly DONE with the EEG. It has been years since I've seen her cry like that. She actually asked for Jasper, her oldest and most beloved teddy bear, and wouldn't let go of him for the rest of the afternoon.

I think I understand what she was feeling. Even though she was probably too young to remember much of it now, I think on some subconscious level, Schuyler was suddenly back in 2003 again, being tested and evaluated and confused by medical procedures which could not have possibly made any sense to her. For a while, Julie and I were in 2003 again. Not because of anything that was actually happening today, because really, the EEG was just about the least traumatic procedure imaginable. Nothing painful except for the irritation in her eyes (and really, that was just the blue icing on the already unhappy cake at that point), and no one was treating her like a patient instead of a person. And yet, the underlying feeling was the same.

Sometimes, most of the time, the monster isn't a thing we face. It's a thing we fear, a thing that exists not as a reality, which can be shitty but is at least something that can be grappled with, but instead as a growling "What If?" in the dark. When Julie saw Schuyler asleep on that bed, her head wrapped in wires and full of innocent little girl dreams, she cried, because that's how she purges it. She cries and then she gets back to work. I sat in a chair next to the bed, the lights turned down low as I watched my little girl sleep, and for a few minutes I let myself give in to the gathering gloom, the shadow that seems to creep around Schuyler in those moments. I didn't cry so much as let the feeling grip me. Tears in my eyes, perhaps, but not crying so much as feeling that little pit as it opened again, the one that we first saw six years ago and only occasionally have to peek into.

And then we pull ourselves together, we dispel the fears, if only for a little while, and when the lights come on, the shadows recede. And we get back to work.

We ask black and white questions, and we receive grey answers in return. And when I think about it, I guess that's probably for the best. I've seen far too many families who looked for black and white answers and only got black ones. I'll take grey.

January 4, 2009

"There will be snacks..."

A Confederacy of Monsters

On Tuesday, the trade paperback version of my book comes out. On Thursday, I have an author event at a fancy venue, with good friends there. And the thing is, I am really very excited about it all. But at the same time it feels distant, like party sounds coming from the house next door. My focus, borne out of five and a half years of vague anxiety suddenly made real, is aimed like a laser on tomorrow.

Tomorrow's the day. Tonight, Schuyler and I will stay up all night watching scary monster movies. (If you saw the lineup, you'd either be jealous or you'd call Child Services.) Tomorrow, a neurologist will glue sensors to her pretty head and attempt to flush out her monster.

I'm not asking for your prayers, because you know how I feel about your God and what he's done to my child. But I hope you'll think good thoughts for us and send whatever positive energy you can in Schuyler's direction. Could that represent the same thing? Perhaps. All I know is that we need answers, once again.

I wanted to take a photo of Schuyler for this entry, so I went in her room and asked her to grab her favorite monster. She picked this guy, a gift from my editor at St. Martin's. As I took photo after photo, she began explaining to me about tomorrow, about what they were going to do, and why. I was really surprised to see that she was processing this EEG and the reasons behind it; I've explained it to her, but I wasn't sure she got it until now.

Even more interesting to me was that Schuyler understood the connection between the monster in her lap and the one in her head. I get the sense that she loves them both, in her weird little way.

January 2, 2009

Izzie

Longtime readers will know that I love dwarf hamsters. I once even ran an information site about them, which just goes to show you that everyone loves something weird and has a secret passion. Mine, as far as you know, is dwarf hamsters. There's weirder stuff to like out there than dwarf hamsters. Trust me.

My favorite dwarf hamster is the Roborovski hamster, and not just because of the name. Roborovskis are the smallest of the hamsters, and they're quite a bit different from their cousins. They live about twice as long, they don't mate as often, and while they are much more active and twitchy, they are also much friendlier than other breeds of hamsters. I've never been bitten by a Roborovski hamster. They're not very cuddly except with each other and don't really like to be handled, but they are otherwise very sociable little guys and I just love 'em.

There is a special mutation that has recently been bred in Roborovskis that results in white-faced hamsters, and when I found one and brought it home with a normal Roborovski mate, I was as happy as I could be. The brown hamster I named Tristan, and the white girl Isolde. I quickly came to call her Izzie.

A few months after she came home with me, I found Izzie one morning, lying on her side in her cage. Her eyes were open and she was alert, but it was clear that something was terribly wrong. She could barely walk and dragged herself on one side. I was heartbroken. Strokes are fairly common in hamsters, and there's not much you can do for them when they strike, except just make them comfortable. I didn't know what else to do for Izzie; I certainly wasn't going to try to put her out of her misery. I mean, how would you do that, anyway? So I watched her sadly, and I waited for the end that seemed sure to come.

Over a year later, I'm still waiting.

This isn't the story of a poor dead hamster; she's still around and still kicking. This is the story of a pretty little thing that suddenly became a twisted, skinny little scrap with bugged eyes and a funny walk. Izzie didn't die, and while she didn't exactly get all better, she did figure out how to walk around fairly quickly, and how to keep herself steady when she drank from the water bottle. Tristan became very protective and nurturing to her, hardly ever leaving her side, and so for the past year or so, I've watched these two hamsters, named after famous but doomed lovers. They've written their own story, however, and so far, it's been a happy one.

Every day, I go to their cage and I find Izzie sleeping, curled up grotesquely like a dead bug, her eyes half open. She looks dead every time, and so I remove the lid to the cage and blow gently on her. I can't help myself. And every time I do, she pops up, rudely awakened, and looks up at me with her bulging eyes as if to say, "Dude. Fucking quit it already." She is unmoved by my concern.

Izzie's not a metaphor for some larger issue, as tempting as it might be to try to turn her into one. She's simply a tough little hamster who refuses to die like she was supposed to, and her fat little mate seems to love her without limits. Every day I watch them, and I wonder about this world in which it is the broken and the seemingly forsaken that fight the hardest, for an existence that the rest of us take for granted. So I don't know. Perhaps she is a pretty good metaphor.

She still hates it when you blow on her, though.

My favorite dwarf hamster is the Roborovski hamster, and not just because of the name. Roborovskis are the smallest of the hamsters, and they're quite a bit different from their cousins. They live about twice as long, they don't mate as often, and while they are much more active and twitchy, they are also much friendlier than other breeds of hamsters. I've never been bitten by a Roborovski hamster. They're not very cuddly except with each other and don't really like to be handled, but they are otherwise very sociable little guys and I just love 'em.

There is a special mutation that has recently been bred in Roborovskis that results in white-faced hamsters, and when I found one and brought it home with a normal Roborovski mate, I was as happy as I could be. The brown hamster I named Tristan, and the white girl Isolde. I quickly came to call her Izzie.

A few months after she came home with me, I found Izzie one morning, lying on her side in her cage. Her eyes were open and she was alert, but it was clear that something was terribly wrong. She could barely walk and dragged herself on one side. I was heartbroken. Strokes are fairly common in hamsters, and there's not much you can do for them when they strike, except just make them comfortable. I didn't know what else to do for Izzie; I certainly wasn't going to try to put her out of her misery. I mean, how would you do that, anyway? So I watched her sadly, and I waited for the end that seemed sure to come.

Over a year later, I'm still waiting.

This isn't the story of a poor dead hamster; she's still around and still kicking. This is the story of a pretty little thing that suddenly became a twisted, skinny little scrap with bugged eyes and a funny walk. Izzie didn't die, and while she didn't exactly get all better, she did figure out how to walk around fairly quickly, and how to keep herself steady when she drank from the water bottle. Tristan became very protective and nurturing to her, hardly ever leaving her side, and so for the past year or so, I've watched these two hamsters, named after famous but doomed lovers. They've written their own story, however, and so far, it's been a happy one.

Every day, I go to their cage and I find Izzie sleeping, curled up grotesquely like a dead bug, her eyes half open. She looks dead every time, and so I remove the lid to the cage and blow gently on her. I can't help myself. And every time I do, she pops up, rudely awakened, and looks up at me with her bulging eyes as if to say, "Dude. Fucking quit it already." She is unmoved by my concern.

Izzie's not a metaphor for some larger issue, as tempting as it might be to try to turn her into one. She's simply a tough little hamster who refuses to die like she was supposed to, and her fat little mate seems to love her without limits. Every day I watch them, and I wonder about this world in which it is the broken and the seemingly forsaken that fight the hardest, for an existence that the rest of us take for granted. So I don't know. Perhaps she is a pretty good metaphor.

She still hates it when you blow on her, though.

December 31, 2008

"And next year's words await another voice..."

I haven't done one of those end-of-the-year wrap-ups for a long time, mostly because I think they are usually more interesting to write than to actually read. It's probably like hearing about someone's dreams, except worse, because if you've been reading for at least a year, you end up thinking "Yeah, I know, I was there for that."

But I don't know, this year feels different. 2008 certainly feels more deserving of a self-indulgent recap, as all personal blog annual recaps are required to be, by law. I believe it's a federal law.

For me personally, it was obviously a significant year, and not just because I was thirty-ten and still inexplicably alive. 2008 was the year that I was published. A book. A real, hardcover, not-printed-at-Kinko's, gigantic New York publishing house, "fuck you, trees" book. I did all that work, I wrote 90,000 words that someone wanted to publish, I went through an editing process that was deceptively painless, and one day a box arrived at my apartment that contained something that no one can ever take away from me now. Last week, ending the year, I received another, similar box, this time with paperback copies of this thing that I did, this thing that seems so unlikely even now.

It was never what I set out to do. I never dreamed that I would get picked up by St. Martin's Press, or that I would see my words published in Good Housekeeping or Wondertime. I never expected to get reviewed in People, or to be featured in newspaper articles or on public radio. I certainly never expected to go on television, in interviews that I loved and others that, well, not so much, and in ones where I talked about my faith, something that I rarely do privately, much less for a live television audience. I didn't write the book so I could give big fancy speeches or return to my college as something besides assistant manager at Kentucky Fried Chicken, and I certainly never anticipated being the guest lecturer at a university. I never thought it would reach this level of fancy pantsedness. I even bought a suit.

I have loved every moment of it, and it has been an incredible adventure, one that I don't expect will repeat itself, no matter what I publish in the future. It's been amazing mostly because my family has been along for the ride. I'm not sure how much Julie enjoys living in the light now, although she's been fantastic about the whole thing, but for Schuyler, it's been an amazing trip. She's developed into an even more confident and sociable little girl, if that's possible.

More importantly, I believe the attention from the book has shown Schuyler that she really is unique and different, but far from being a freak, she's a rare creature of beauty and spark. She knows she's broken, but she's also learning that people love her not just despite that, but because of how she deals with it. She understands that she has a monster; suggesting or pretending otherwise is an insult to her, as far as I'm concerned. But because of the book and the attention she's received from it, I like to believe that she also sees that it is in taming that monster and making it small that she has become her own kind of perfect.

And that's really why I wrote the book, and why I wanted to get it out in the world, even if it had only sold 500 copies and gotten remaindered in six months. (Note: It's doing a little better than that, I'm happy to report.) It was my love letter to Schuyler. It was my insurance policy, the thing that would stand for me if I ever got hit by a bus or killed by internet stalkers. She will always have the book, and so in that respect, 2008 was the best year of my life with Schuyler. No matter what, she'll always have that, and will always know what she meant to me, and how much I admire her.

This was a good year for me for making new friends and reconnecting with old ones, mostly because of the book. It hasn't been perfect, of course. I believe resentment is probably responsible for finally killing off at least one friendship, albeit one that was admittedly on tottering legs anyway. I think that's too bad; it's not as if I took someone else's shot at publication away in achieving mine. But for the most part, I've met some really amazing writers over the past year, and I've reconnected with old friends from high school who saw the articles in People and Good Housekeeping. (And just why are people my age reading Good Housekeeping, anyway? Oh, yeah, we're the target demographic now. Time, you suck.) Best of all, I've watched some old but casual friendships deepen and flourish. My friendships are a little like a garden, I suppose. The weeding's not much fun, but it's the new blossoms that take my breath away and remind me of what's good in the world.

I have no idea what to expect from 2009. The year begins with the paperback release of my book, but the day before, it also sees Schuyler's return to the world of doctors and specialists and questions. The other day, Julie very quietly said, "I think Schuyler's PMG is starting to manifest itself more," and I think she might be right. We've both seen more of her little spells, and she's starting to have a slight increase in difficulties with her fine motor skills. She's only signing with her left hand now, for example, and her handwriting seems to be challenging her a little more, too. If I had to sit down and face this thing head-on, I might be forced to admit that when I think of this new year, I am filled with a dread, a persistent feeling that something's coming, and not something nice. I'm Schuyler's father, and I'm prone to considering all the worst-case scenarios, I know. But I also know Schuyler, better than anyone else in the world save one. When she starts to experience changes, we see it. I think we've already done more than enough to convince the world that we know what we're talking about, and yet I suspect we're about to be right back in that swamp again, the one where we're the idiot parents and someone else is The Expert. This time, I think we'll be ready.

Most of all, however, I think that no matter how rough 2009 might turn out to be or how big the monster grows, once again it will be Schuyler who will show me the way. She continues to be the strong one, and the smart one, and most of all the tenacious fighter. I see the monster again after so much quiet time, and I despair. Schuyler sees an ass that she needs to cheerfully kick. That will always be the difference between us, and perhaps it's the way it's supposed to be.

I think about that a lot. How Things Are Supposed To Be. I've never thought this was it, of course. So many people see Schuyler through their own prism, and so she becomes and angel or a savior or whatever she needs to be for them. As she steps into a new year as a nine year-old, Schuyler is everything she is perceived to be, and much more. She's a broken yet priceless doll, sadly incomplete and yet more perfect and beautiful because of it. She's an otherworldly being who speaks in a beautiful but foreign tongue, but she's also the quintessential nine year-old girl who lives in Chuck Taylors and wants to be Kim Possible. She's a chaotic tornado of energy who bristles at authority and thrives on change. Schuyler doesn't need anyone to teach her about God or Jesus or anyone else who has failed her, and yet she's a child of God, like the rest of us. She's a child who deserves an explanation from that Divine Bully, but to whom it will probably never even occur to ask.

As the new year dawns, it's Schuyler whom I'll be watching, and following, and if she can make her way through this grand rough world, one that both fails her and thrills her at ever turn, then I suppose the rest of us can, too.

Besides, she's the only person who likes my moustache, even if just as an object of amusement.

But I don't know, this year feels different. 2008 certainly feels more deserving of a self-indulgent recap, as all personal blog annual recaps are required to be, by law. I believe it's a federal law.

For me personally, it was obviously a significant year, and not just because I was thirty-ten and still inexplicably alive. 2008 was the year that I was published. A book. A real, hardcover, not-printed-at-Kinko's, gigantic New York publishing house, "fuck you, trees" book. I did all that work, I wrote 90,000 words that someone wanted to publish, I went through an editing process that was deceptively painless, and one day a box arrived at my apartment that contained something that no one can ever take away from me now. Last week, ending the year, I received another, similar box, this time with paperback copies of this thing that I did, this thing that seems so unlikely even now.

It was never what I set out to do. I never dreamed that I would get picked up by St. Martin's Press, or that I would see my words published in Good Housekeeping or Wondertime. I never expected to get reviewed in People, or to be featured in newspaper articles or on public radio. I certainly never expected to go on television, in interviews that I loved and others that, well, not so much, and in ones where I talked about my faith, something that I rarely do privately, much less for a live television audience. I didn't write the book so I could give big fancy speeches or return to my college as something besides assistant manager at Kentucky Fried Chicken, and I certainly never anticipated being the guest lecturer at a university. I never thought it would reach this level of fancy pantsedness. I even bought a suit.

I have loved every moment of it, and it has been an incredible adventure, one that I don't expect will repeat itself, no matter what I publish in the future. It's been amazing mostly because my family has been along for the ride. I'm not sure how much Julie enjoys living in the light now, although she's been fantastic about the whole thing, but for Schuyler, it's been an amazing trip. She's developed into an even more confident and sociable little girl, if that's possible.

More importantly, I believe the attention from the book has shown Schuyler that she really is unique and different, but far from being a freak, she's a rare creature of beauty and spark. She knows she's broken, but she's also learning that people love her not just despite that, but because of how she deals with it. She understands that she has a monster; suggesting or pretending otherwise is an insult to her, as far as I'm concerned. But because of the book and the attention she's received from it, I like to believe that she also sees that it is in taming that monster and making it small that she has become her own kind of perfect.

And that's really why I wrote the book, and why I wanted to get it out in the world, even if it had only sold 500 copies and gotten remaindered in six months. (Note: It's doing a little better than that, I'm happy to report.) It was my love letter to Schuyler. It was my insurance policy, the thing that would stand for me if I ever got hit by a bus or killed by internet stalkers. She will always have the book, and so in that respect, 2008 was the best year of my life with Schuyler. No matter what, she'll always have that, and will always know what she meant to me, and how much I admire her.

This was a good year for me for making new friends and reconnecting with old ones, mostly because of the book. It hasn't been perfect, of course. I believe resentment is probably responsible for finally killing off at least one friendship, albeit one that was admittedly on tottering legs anyway. I think that's too bad; it's not as if I took someone else's shot at publication away in achieving mine. But for the most part, I've met some really amazing writers over the past year, and I've reconnected with old friends from high school who saw the articles in People and Good Housekeeping. (And just why are people my age reading Good Housekeeping, anyway? Oh, yeah, we're the target demographic now. Time, you suck.) Best of all, I've watched some old but casual friendships deepen and flourish. My friendships are a little like a garden, I suppose. The weeding's not much fun, but it's the new blossoms that take my breath away and remind me of what's good in the world.

I have no idea what to expect from 2009. The year begins with the paperback release of my book, but the day before, it also sees Schuyler's return to the world of doctors and specialists and questions. The other day, Julie very quietly said, "I think Schuyler's PMG is starting to manifest itself more," and I think she might be right. We've both seen more of her little spells, and she's starting to have a slight increase in difficulties with her fine motor skills. She's only signing with her left hand now, for example, and her handwriting seems to be challenging her a little more, too. If I had to sit down and face this thing head-on, I might be forced to admit that when I think of this new year, I am filled with a dread, a persistent feeling that something's coming, and not something nice. I'm Schuyler's father, and I'm prone to considering all the worst-case scenarios, I know. But I also know Schuyler, better than anyone else in the world save one. When she starts to experience changes, we see it. I think we've already done more than enough to convince the world that we know what we're talking about, and yet I suspect we're about to be right back in that swamp again, the one where we're the idiot parents and someone else is The Expert. This time, I think we'll be ready.

Most of all, however, I think that no matter how rough 2009 might turn out to be or how big the monster grows, once again it will be Schuyler who will show me the way. She continues to be the strong one, and the smart one, and most of all the tenacious fighter. I see the monster again after so much quiet time, and I despair. Schuyler sees an ass that she needs to cheerfully kick. That will always be the difference between us, and perhaps it's the way it's supposed to be.

I think about that a lot. How Things Are Supposed To Be. I've never thought this was it, of course. So many people see Schuyler through their own prism, and so she becomes and angel or a savior or whatever she needs to be for them. As she steps into a new year as a nine year-old, Schuyler is everything she is perceived to be, and much more. She's a broken yet priceless doll, sadly incomplete and yet more perfect and beautiful because of it. She's an otherworldly being who speaks in a beautiful but foreign tongue, but she's also the quintessential nine year-old girl who lives in Chuck Taylors and wants to be Kim Possible. She's a chaotic tornado of energy who bristles at authority and thrives on change. Schuyler doesn't need anyone to teach her about God or Jesus or anyone else who has failed her, and yet she's a child of God, like the rest of us. She's a child who deserves an explanation from that Divine Bully, but to whom it will probably never even occur to ask.

As the new year dawns, it's Schuyler whom I'll be watching, and following, and if she can make her way through this grand rough world, one that both fails her and thrills her at ever turn, then I suppose the rest of us can, too.

Besides, she's the only person who likes my moustache, even if just as an object of amusement.

For last year's words belong to last year's language

And next year's words await another voice.

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

~T.S. Eliot

December 24, 2008

"Hoping it might be so..."

It being Christmas Eve, Schuyler and I went to see Santa this afternoon. This year, we continued our streak of good Santas. After she sat down with him and introduced herself with her device, Schuyler handed him her carefully handwritten note, which he was actually able to decipher. They spoke softly for a while (he reminded her to leave him some cookies, and then flashed me a quick smile as if to say "Dude, you owe me one"), and then, as she was getting up to leave, he held up his hand and stopped her.

"Now, Schuyler," Santa said, "because you've been so good this year, and because you're such a unique little girl, I'm going to give you something that no other child is getting today." He reached down into a chest next to his chair and pulled out a large red sleighbell, ala Polar Express. He gave it to her and then whispered something in her ear. She smiled hugely and hopped away, ringing her little bell.

As we left the little stage area, I saw one of the helpers watching the whole scene. She was actually crying a little, and when she saw me looking at her, she smiled at me and wiped her eyes. "I'm sorry, she said, "but that was just so sweet! He hasn't done that for anyone else that I know of."

As we left, Schuyler was obsessed with the bell. She rang it and peered at it carefully. She seemed to be working something out in her head. Finally she said, "Daddy?"

I looked down at her. "Why?" she asked, indicating the bell.

"Why did Santa give that to you, and no one else?" I asked, making sure I understood the question. She nodded. I thought about it for a moment.

"Well, Santa said you were 'unique'. That means there's not another little girl in the whole world like you, and that's true. Did you know there's no one else anywhere who talks like you do, Schuyler?"

"Really?" she asked.

"Really. That's why you have to use your device to tell us all things. Your words are so special that no one else is smart enough to understand them. That's why he called you 'unique'. You're the most special little girl in the world. There's only one Schuyler anywhere, and I've got you. That makes me pretty unique, too."

She liked that answer.

I know my answer sort of flies in the face of what I'm always saying, about how I don't like People First Language because it sugarcoats disability and blinks when facing the monster head on. But I don't know, I guess on Christmas Eve of all days, I permit myself to believe that perhaps Schuyler's strange words aren't necessarily broken, but from some other world that I'll never be able to visit but which, through her, I get to glimpse.

In 1 Corinthians, St. Paul describes the tongues of angels, unintelligible to us. Maybe, just maybe, this is what he meant. On today of all days, even in my deeply held agnosticism, I'm like Thomas Hardy in his poem "The Oxen". I'm not inclined to believe in miracles, but that doesn't mean I don't pay attention to the things around me, like Schuyler, that sometimes seem miraculous.

I don't necessarily believe, but sometimes I hope, and that might just be enough.

The Oxen

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock,

"Now they are all on their knees",

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

"Come; see the oxen kneel

"In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know",

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

"Now, Schuyler," Santa said, "because you've been so good this year, and because you're such a unique little girl, I'm going to give you something that no other child is getting today." He reached down into a chest next to his chair and pulled out a large red sleighbell, ala Polar Express. He gave it to her and then whispered something in her ear. She smiled hugely and hopped away, ringing her little bell.

As we left the little stage area, I saw one of the helpers watching the whole scene. She was actually crying a little, and when she saw me looking at her, she smiled at me and wiped her eyes. "I'm sorry, she said, "but that was just so sweet! He hasn't done that for anyone else that I know of."

As we left, Schuyler was obsessed with the bell. She rang it and peered at it carefully. She seemed to be working something out in her head. Finally she said, "Daddy?"

I looked down at her. "Why?" she asked, indicating the bell.

"Why did Santa give that to you, and no one else?" I asked, making sure I understood the question. She nodded. I thought about it for a moment.

"Well, Santa said you were 'unique'. That means there's not another little girl in the whole world like you, and that's true. Did you know there's no one else anywhere who talks like you do, Schuyler?"

"Really?" she asked.

"Really. That's why you have to use your device to tell us all things. Your words are so special that no one else is smart enough to understand them. That's why he called you 'unique'. You're the most special little girl in the world. There's only one Schuyler anywhere, and I've got you. That makes me pretty unique, too."

She liked that answer.

I know my answer sort of flies in the face of what I'm always saying, about how I don't like People First Language because it sugarcoats disability and blinks when facing the monster head on. But I don't know, I guess on Christmas Eve of all days, I permit myself to believe that perhaps Schuyler's strange words aren't necessarily broken, but from some other world that I'll never be able to visit but which, through her, I get to glimpse.

In 1 Corinthians, St. Paul describes the tongues of angels, unintelligible to us. Maybe, just maybe, this is what he meant. On today of all days, even in my deeply held agnosticism, I'm like Thomas Hardy in his poem "The Oxen". I'm not inclined to believe in miracles, but that doesn't mean I don't pay attention to the things around me, like Schuyler, that sometimes seem miraculous.

I don't necessarily believe, but sometimes I hope, and that might just be enough.

The Oxen

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock,

"Now they are all on their knees",

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

"Come; see the oxen kneel

"In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know",

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

-- Thomas Hardy

A good review from some brain people

An article about Schuyler's Monster appeared in the December 18, 2008 edition of Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology. It's a positive review and analysis of the book and its place in the ongoing discussion of the complicated relationship between physicians and the patients in their care.

The article, by Mary Jo Harbert, MD and Doris Trauner, MD, is titled "What We As Physicians Can Learn From Our Patients". The thing I like about this article is that it comes from a new perspective for me. This article is written by, and for, neurologists and physicians, and getting their stamp of approval means a great deal to me. More importantly, Drs. Harbert and Trauner understand one of the more important points I was hoping to make with the book.

The article, by Mary Jo Harbert, MD and Doris Trauner, MD, is titled "What We As Physicians Can Learn From Our Patients". The thing I like about this article is that it comes from a new perspective for me. This article is written by, and for, neurologists and physicians, and getting their stamp of approval means a great deal to me. More importantly, Drs. Harbert and Trauner understand one of the more important points I was hoping to make with the book.

"For doctors, this book reminds us that children with developmental disabilities also need to be challenged, just as neurotypical children do, so that they can maximize their potential."That makes me happy.

December 21, 2008

December 18, 2008

9

This Sunday is Schuyler's ninth birthday. Yeah, that's right. Nine. I'm not sure how that happened. I still remember her as a little baby, all fat and hairy and weird. At some point, someone replaced her with a little girl. I'd like an explanation for that, because it has left me feeling quite befuddled.

Anyway, instead of more deep dark scary talk about the monster, I thought I'd share some random observations about Schuyler, in no particular order and not of any earth-shattering importance. Really, I just like thinking about all the weird little things she does. She's a weird kid, "my weird and wondrous monster-slayer", as I call her in the dedication of my book.

So, some quick facts about Schuyler, at nine:

---

Schuyler still loves fairies and dinosaurs and mermaids. She likes princesses, but her favorite book right now is about princesses who kick ass in various nontraditional ways, so I'm not too worried.

Schuyler's brief interest in Hannah Montana appears to be over.

Schuyler's Martian is becoming easier to understand, and yet, there are still intriguing gaps. When she sees a Mini Cooper, for example, she gets excited (she got accustomed to watching for them back when I was going to get one over the summer), and she points and says "Mini!" But it doesn't sound like "mini", not even close. It's a word that she gets the vowels wrong on, too. Martian is a more complicated language than I thought, apparently.

Schuyler can go on a six hour car ride with me, and the return ride a few days later, without a word of complaint. As long as I play my cool "Atomo Mix" in the car, she's all good. But only if I start with the Ali Dee and The Deekompressors version of the Speed Racer theme.

Schuyler is now 4 feet, five inches tall. When the nurse told us that, I thought it had to be a mistake. Babies aren't that tall. I am clearly not dealing well with the passage of time.

For all her height, Schuyler only weighs sixty-eight pounds. She is all arms, legs, ears and front teeth. And giant hypnotic eyes. She's like an anime character.

Schuyler still loves fairies and dinosaurs and mermaids. She likes princesses, but her favorite book right now is about princesses who kick ass in various nontraditional ways, so I'm not too worried.

Schuyler's brief interest in Hannah Montana appears to be over.

Schuyler's Martian is becoming easier to understand, and yet, there are still intriguing gaps. When she sees a Mini Cooper, for example, she gets excited (she got accustomed to watching for them back when I was going to get one over the summer), and she points and says "Mini!" But it doesn't sound like "mini", not even close. It's a word that she gets the vowels wrong on, too. Martian is a more complicated language than I thought, apparently.

Schuyler can go on a six hour car ride with me, and the return ride a few days later, without a word of complaint. As long as I play my cool "Atomo Mix" in the car, she's all good. But only if I start with the Ali Dee and The Deekompressors version of the Speed Racer theme.

Schuyler is now 4 feet, five inches tall. When the nurse told us that, I thought it had to be a mistake. Babies aren't that tall. I am clearly not dealing well with the passage of time.

For all her height, Schuyler only weighs sixty-eight pounds. She is all arms, legs, ears and front teeth. And giant hypnotic eyes. She's like an anime character.

Schuyler's lost glasses mysteriously appeared in the teacher's lounge at her school a few weeks after they vanished. They were even still in the case. Not sure what to make of that. We decided just to accept it as a gift from the universe and move on.

Schuyler's love of Chuck Taylors has not abated at all.

Schuyler is now wearing women's size six shoes. She is one shoe size behind her mother now. Adult sized Chuck Taylors are twice as expensive as the identical kid sizes.

Schuyler makes up names for her toy friends, names that are strange and kind of wonderful. Her new triceratops from the Field Museum, for example, is named Yliksa. At first I thought she was just randomly stringing letters together, but no. When quizzed about it repeatedly, she always gets the spelling the same, and gets upset if we get it wrong. I sometimes wonder if these are popular names on Mars.

Schuyler loves soccer and baseball, but hates football so much that she boos when she sees it on tv or being played by other kids. I'm pretty sure she does that for my benefit. She is truly a coach's grand-daughter.

Schuyler met a friend of mine via videoconferencing a few weeks ago, and now refers to my "friend in the computer". She's going to lose her mind when they meet in person in a few weeks.

When she signs books now, Schuyler has taken to writing things like "Love, Schuyler!" (Always with the exclamation point.) It slows down the line at book signings, but I don't think anyone minds.

If you can catch her without her noticing, Schuyler is an amazing and beautiful photographic subject. If you ask her to smile, however, she will squint and make what she thinks is a smile but which looks more like a pained grimace. It looks more like a painful pooping face than a smile. For two years in a row, the school photographer has apparently told her to smile.

Schuyler still spots police cars for me. "The fuzz! The fuzz!"

If Schuyler turns out to be having seizures, we'll have to get rid of her cool loft bed. It would be far too difficult for one of us to get up to her if she had a seizure up there. I'm not sure why, but lately, this is the thing that has been making me the saddest about the possibility of seizures.

Schuyler will try any food, and she's not afraid of spicy things.

Schuyler is transfixed by ballet. She was watching the San Francisco Ballet's Nutcracker on tv, and you would have thought there were dinosaurs, eating princesses and chocolate ice cream at the Purple Cow. She was mesmerized. Afterwards, she danced around on her toes for the rest of the night.

Schuyler lost that little kid belly that she always had when she was young, the one that all little kids have. She is tall and slender and has an actual girl butt. I find this to be very troubling, and it only gets worse from here on out.

Schuyler did a paper on leopards this semester. She presented it while wearing a leopard print skirt that she picked out herself for the occasion.

Schuyler picks almost all her own clothes. She puts the outfits together, too, although we exercise veto rights. Well, you would, too.

Schuyler and my mother have a very close and sort of wordless bond that is unlike any other in her life. It's hard to describe, but it makes me happy.

When Schuyler looks sad, she looks like my grandmother, who has the saddest story in all my family. But she doesn't look sad very often.

Schuyler loves babies. She would have been an amazing big sister.

Schuyler is my best friend and the finest daughter a father could ever dream of having. I'm not sure where she comes from and what that other world is like, the one that she visits us from, but I'm inexpressibly happy that she spends time in my world, too.

Happy birthday, Chubbin.

Schuyler's love of Chuck Taylors has not abated at all.

Schuyler is now wearing women's size six shoes. She is one shoe size behind her mother now. Adult sized Chuck Taylors are twice as expensive as the identical kid sizes.

Schuyler makes up names for her toy friends, names that are strange and kind of wonderful. Her new triceratops from the Field Museum, for example, is named Yliksa. At first I thought she was just randomly stringing letters together, but no. When quizzed about it repeatedly, she always gets the spelling the same, and gets upset if we get it wrong. I sometimes wonder if these are popular names on Mars.

Schuyler loves soccer and baseball, but hates football so much that she boos when she sees it on tv or being played by other kids. I'm pretty sure she does that for my benefit. She is truly a coach's grand-daughter.

Schuyler met a friend of mine via videoconferencing a few weeks ago, and now refers to my "friend in the computer". She's going to lose her mind when they meet in person in a few weeks.

When she signs books now, Schuyler has taken to writing things like "Love, Schuyler!" (Always with the exclamation point.) It slows down the line at book signings, but I don't think anyone minds.

If you can catch her without her noticing, Schuyler is an amazing and beautiful photographic subject. If you ask her to smile, however, she will squint and make what she thinks is a smile but which looks more like a pained grimace. It looks more like a painful pooping face than a smile. For two years in a row, the school photographer has apparently told her to smile.

Schuyler still spots police cars for me. "The fuzz! The fuzz!"

If Schuyler turns out to be having seizures, we'll have to get rid of her cool loft bed. It would be far too difficult for one of us to get up to her if she had a seizure up there. I'm not sure why, but lately, this is the thing that has been making me the saddest about the possibility of seizures.

Schuyler will try any food, and she's not afraid of spicy things.

Schuyler is transfixed by ballet. She was watching the San Francisco Ballet's Nutcracker on tv, and you would have thought there were dinosaurs, eating princesses and chocolate ice cream at the Purple Cow. She was mesmerized. Afterwards, she danced around on her toes for the rest of the night.

Schuyler lost that little kid belly that she always had when she was young, the one that all little kids have. She is tall and slender and has an actual girl butt. I find this to be very troubling, and it only gets worse from here on out.

Schuyler did a paper on leopards this semester. She presented it while wearing a leopard print skirt that she picked out herself for the occasion.

Schuyler picks almost all her own clothes. She puts the outfits together, too, although we exercise veto rights. Well, you would, too.

Schuyler and my mother have a very close and sort of wordless bond that is unlike any other in her life. It's hard to describe, but it makes me happy.

When Schuyler looks sad, she looks like my grandmother, who has the saddest story in all my family. But she doesn't look sad very often.

Schuyler loves babies. She would have been an amazing big sister.

Schuyler is my best friend and the finest daughter a father could ever dream of having. I'm not sure where she comes from and what that other world is like, the one that she visits us from, but I'm inexpressibly happy that she spends time in my world, too.

Happy birthday, Chubbin.

December 15, 2008

Monster hunt

In real life, events do not wait for the proper moments in perfect chapter order.

There are really two things going on right now that are taking most of my attention. On one hand, my book will be released in trade paperback on January 6th, followed shortly by new author appearances at a number of locations. For the paperback, I'm trying to focus on independent bookstores and want to visit different parts of the country where so many of you who have asked might actually be able to attend. (I'm looking at you, San Francisco.) Two days after the book release, I'll be at the amazing new Legacy Books here in Plano.

(If you live in the area, you should really come. The store is huge and beautiful and has a liquor license. And as an additional bonus, my lovely friend Monique van den Berg will be there. She's an exceptional and popular writer who was kind enough to contribute study guide questions for the paperback edition of Schuyler's Monster. I suspect that between Monique and Schuyler, I will be the third biggest audience draw to my own signing. I can live with that.)

So that's the week of the paperback release.

The day before the book release, Schuyler has an EEG, to determine if she is having absence seizures.

Okay, so let's talk about the seizures.

The test itself should be interesting. It's called a "Sleep Deprived EEG", and that's exactly what it is. The night before, Schuyler is not allowed to sleep more than four hours (and preferably not at all), which of course means that someone will have to stay up with her. Given my regular insomnia, the job will fall to me. Julie will sleep and be ready to do all the driving (and listening, and thinking, really) the next day, and I will be up with Schuyler all night, probably watching monster movies and whatever else I can think of. When she's a zombie the next day, I'll be there with her, hungering for brains.

The next morning, neurologists will glue little sensors all over Schuyler's head, flash some lights in her face and then send her off to sleep for an hour or so. The idea is that the lack of sleep and the fancy light show will trigger seizures that will then be recorded by the EEG. (Remind me to add Speed Racer to the all-night film line-up; it's one of her favorites, and if anything will trigger seizures, it's that movie.)

The problem with this test is that it can only prove a positive, not provide a conclusive negative. If she has a seizure during that hour or so, then we know she's having them. But if not, all it means is that she didn't have a seizure during that time period. After that, if nothing was seen, I believe the next step is an ambulatory EEG, in which she is wired up to a portable sensor unit like a little laboratory capuchin monkey and sent into the gawking world for twenty-four hours. I have no doubt that Schuyler would love that. She flies her freak flag higher and more proudly than anyone I know.

So that's what's next. If there's a little monster waiting, we will flush it out. Well, I shouldn't be overly dramatic about this. We don't actually know that she's even having absence seizures at all. She turns nine this coming Sunday, after all; there's a condition that that causes an inability to focus that many nine-year-olds suffer from. It's called being nine.