Waiting two months to see a neurologist sounds like a long time, even though I'm told that it's really not. Well, it is a long time, but I guess I should say that it's not an unusual wait; it's actually pretty good compared to the wait that many parents and patients endure. Most people end up waiting months, and that's right here in America. I can't tell you how many times I've read conservatives disparaging the Canadian health care system's long waits when they are listing the failures of socialized medicine. As far as I can tell, the big difference between that system and the one we have here in God's Perfect Perfect Country is the fact that we'll get a gigantic bill for our trouble. Well, what are you going to do?

It's frustrating, in part because we're trying to catch a very elusive monster. Schuyler hasn't had consistent issues with this, after all. She had a few "incidents" back in January, and then again two weeks ago (and twice last week since I last wrote about this). This week? Nothing so far. What we'll be hoping for is IF she's having seizures, and we don't know that she is, she'll just happen to have one of them while she has wires connected to her head in about six weeks. If we could have gone to the neurologist's office when she was having these incidents, then we would have a better shot at catching one as it happens. Doing it this way is like finding evidence of some animal in the forest and then returning with a gun two months later, hoping it might come back. And not knowing if it's a rabbit or a bear. Or a Tyrannosaur.

Identifying absence seizures is hard because they are so hard to recognize, and in Schuyler's case, the evidence that she might have had one follows the actual seizure itself, IF she's having them. If if if if if if if. Fucking ifs rule our lives now.

I don't know if she's having seizures. We continue to rule out the other possibilities, such as UTIs and blood sugar issues, but that process of elimination isn't much help. From what I've read, it's not unusual for absence seizures to go unrecognized or unobserved for years. Do you know when some kids discover they're having them? When they start driving. Think about that. Spacing out for a few seconds in class or at home goes unnoticed for years, easily, but imagine your child having one at 70 mph on the freeway. Assuming your kid survives, congratulations! Now you know they're having seizures.

Well, Schuyler's eleven, and she still doesn't ride a bicycle, so that's a fun fear that I can put off for a while. It's good to pace yourself, after all.

When we learned of Schuyler's polymicrogyria almost eight years ago (God, I can't believe it's been that long), this wasn't what we expected. I suspect that's true for a lot of parents. You imagine the Big Event, you imagine that first seizure arriving like a hurricane or an earthquake. You don't think about the possibility that you just might not know, it might take years to discover the truth.

There's a lot I don't know. I don't know if Schuyler is having seizures. I don't know if she's significantly (and permanently) impaired intellectually. Will she ever catch up to her classmates? Will she graduate from high school one day? Will she drive a car and live in an apartment and have a job? Will she date boys and get married? Will she date girls and scandalize her grandparents? When I die, will she cry her tears and then move on with her independent life? Will the monster that holds her back now begin to gently release its grip on her as she gets older, or will it one day crush her in its hands? I don't know. I can't know.

Other parents worry about their neurotypical or otherwise unafflicted children's futures, I get that. But not like this. I wish I knew how to explain to those parents, the ones who try to cheer us up by telling us how they worry about their kids, too, just like us, that no, they don't. I wish I could make them see that the things that worry them, things like good grades or their daughters' first periods or their kids' lives after high school, these things terrify us. Even the usual stuff is hard, the stuff we can see coming. The thing you learn with a kid like Schuyler is that even the boring stuff goes down differently with her. You think you know how it'll play out, but you don't.

Sometimes I feel like the worst thing that happened to Schuyler was simply that she was our first born. After Schuyler, we made the decision not to risk more children, and while that has been a source of some sadness over the years, it was nevertheless exactly the correct choice to make. But if we'd had another child before Schuyler, if she had an older, neurotypical sibling, then at least she wouldn't be as alone as she is. I don't know, though. Maybe it wouldn't be any better. Schuyler is loved by a great many people, including members of her family, but the harsh truth is that the reality of her situation is understood by very very few. Our friends, our co-workers, and both our families want to get it, to get her, but they don't. And really, I don't know that they can.

Because honestly, I don't know that Julie or I do, either, although I know we get closer than anyone else. Some of her teachers have probably gotten close from time to time, too. The hope and the enthusiasm we all felt when we first moved to Plano has been replaced by some grey truths. Schuyler can be difficult to teach. Schuyler can be age-appropriate in some ways and astonishingly delayed in others. A world in which she can attend mainstream classrooms and learn alongside her neurotypical classmates seems more out of reach now than ever before. And she might be having seizures.

Sometimes when I write about Schuyler, I have a point that I'm trying to make. I take my topic and I use my skills as a writer to present it, sculpted and shaped into something that works as an essay, something that might have meaning and value to others. But every now and then, when I feel overwhelmed both by the way things are and the unknown and the unknowable, I just start writing, just let my anxieties flow out without shape or craft. No art, just "fuck".

Sorry, but yeah. Fuck.

Schuyler is my weird and wonderful monster-slayer. Together we have many adventures.

March 15, 2011

March 4, 2011

Polly

You watch for the big monsters. You brace for them, wait for them to come so you can wrestle with them, your feet firmly in place, set for the match. But the thing is, when they arrive, they never feel like big monsters. They don't even reveal themselves all at once. They quietly walk into the room, never in the light but rather in the shadows at the edges. It can take a long time to notice that they're even there, and to identify what they are.

Two years ago, we faced the possibility that Schuyler was beginning to have absence seizures. This was tough, but not unexpected; the majority of kids with polymicrogyria, as many as 85-90% of them, develop seizures. Over the next couple of months, we went trough the whole process of EEG evaluation, including a fun test where Schuyler had wires glued to her head for a whole weekend. That test was ultimately inconclusive. It didn't record any outright seizures, but it did show a "significant neurological event" occurring periodically on the left side of her brain while she slept. Her neurologist had no idea what it was, only what it wasn't. No seizures, not yet, but maybe... something.

I hate writing about something that might embarrass Schuyler one day, but it's kind of hard to avoid at this point, so I apologize in advance. A few weeks ago, out of the blue, Schuyler had an accident. She peed her pants. A few days later, it happened again. Both times she said she tried to get to the bathroom in time, but didn't make it. She explained, as best as she could, that it just happened. One minute she didn't have to go, and the next, it was too late.

Last night, at the house of a friend, it happened again, catching her completely by surprise. And then tonight, after we got home from school, one minute she was sitting down with her Happy Meal, and the next, she was running to the bathroom, in vain. Another accident.

On none of these occasions was anyone actively observing her in the exact moment. But we know the warning signs; we've known them for years, always kept them in the back of our minds.

So again we brace ourselves, not for that often-imagined moment when Schuyler falls to the floor in a grand mal seizure and suddenly It Has Come, but rather for the suspicion, the realization that something may already be happening, that the odds may have caught up with her at last. Last time, we wondered because Schuyler had been spacing out from time to time. This time, the signs are even more compelling. And again, we'll put Schuyler in the hands and the sensors of a neurology team in the hopes that they may have their crown of wires attached to her at an opportune moment so that we can finally know if this is beginning in earnest.

Schuyler is eleven now, and we believe that she's old enough for a little more adult conversation about this. She's known about her condition for a while. A number of people have written to me over the years, afraid that words like "broken" and "monster" were going to scar her somehow, but the fact is that we've had some version of this conversation going with her all along. People afraid of how Schuyler might feel if she read my words one day are missing the point. She's been hearing the words, she's been soaking up the concept. Hiding her reality from her would be wrong, and it would be pointless. She faces the big truths in her own way; she processes them in her own time.

She was feeling humiliated by her accident tonight, as she had the night before, so I sat down with her and explained that these accidents might not be her fault. I told her that the same thing in her brain that makes it hard for her to speak clearly, the thing that causes her to drool sometimes and keeps her from eating some foods, that thing might also be causing her to pee her pants every now and then. I explained how our brains run on electricity (which she thought was pretty cool), and that some brains use too much electricity sometimes, which causes them to overload. Those overloads are called seizures, I told her. Some of them are brief and small, so small that the person doesn't know that they had them, while others are bigger.

I told her that we will have to see a doctor again to be sure, but that she might be having those little seizures, and if she is, that might be causing her to pee her pants. I told her that these seizures were cause by the thing in her brain that made her different.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"What's what called?"

She pointed to her head. "The little monster in my brain."

It occurred to me that I might not have ever actually told her this part. "It's got a long name, it's called polymicrogyria."

She thought about that for a moment, and then laughed. "That's a funny name," she said.

"Do you want to call it something else?" I asked.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"Polymicrogyria."

She laughed. "I know, I know!" (She says "I know, I know!" a lot when she gets excited.) "It's Polly the Monster!"

I see a monster that may finally be giving my little girl seizures, might be delivering on the ugly promise we'd been made when Schuyler was diagnosed almost eight years ago, and I feel my heart drop again.

Schuyler sees that monster, and she nicknames it Polly.

As we drove to pick up Julie at work, Schuyler sat quietly in the passenger seat, processing. Finally she turned to me.

"Daddy? I don't want a little monster in my brain."

She said it seriously but not somberly, sad but not crushed. I told her that I didn't want her to have it, either, but there was nothing we could do but make the very best of it, the same as we always had.

She shrugged a little and said, "I know."

Later, she asked Julie if she was sad. She said it with concern for her mother, but I didn't get the sense that she was terribly sad herself. I mean, she wasn't thrilled by this new situation, but she was processing it already, moving faster than we were, perhaps sensing that some very hard stuff may be waiting in the near future but already impatient with the sad.

"I know." She knows.

Two years ago, we faced the possibility that Schuyler was beginning to have absence seizures. This was tough, but not unexpected; the majority of kids with polymicrogyria, as many as 85-90% of them, develop seizures. Over the next couple of months, we went trough the whole process of EEG evaluation, including a fun test where Schuyler had wires glued to her head for a whole weekend. That test was ultimately inconclusive. It didn't record any outright seizures, but it did show a "significant neurological event" occurring periodically on the left side of her brain while she slept. Her neurologist had no idea what it was, only what it wasn't. No seizures, not yet, but maybe... something.

I hate writing about something that might embarrass Schuyler one day, but it's kind of hard to avoid at this point, so I apologize in advance. A few weeks ago, out of the blue, Schuyler had an accident. She peed her pants. A few days later, it happened again. Both times she said she tried to get to the bathroom in time, but didn't make it. She explained, as best as she could, that it just happened. One minute she didn't have to go, and the next, it was too late.

Last night, at the house of a friend, it happened again, catching her completely by surprise. And then tonight, after we got home from school, one minute she was sitting down with her Happy Meal, and the next, she was running to the bathroom, in vain. Another accident.

On none of these occasions was anyone actively observing her in the exact moment. But we know the warning signs; we've known them for years, always kept them in the back of our minds.

Typical absence seizures are primary generalized seizures characterized by brief staring episodes, lasting two to 15 seconds (generally less than 10 seconds), with impaired consciousness and responsiveness. They begin without warning (no aura) and end suddenly, leaving the person alert and without postictal confusion. Often, the person will resume preattack activities, as if nothing had happened. Simple absence seizures are characterized by staring spells alone. In complex absence seizures, which are more common, staring is accompanied by automatisms, such as eye blinks or lip smacking; they may include mild clonic, atonic, or autonomic components involving the facial muscles. There may also be a slight nod of the head or semi-purposeful movements of the mouth or hands. The automatisms tend to be stereotyped, with the same behaviors occurring during each seizure. Penry et al observed automatisms in 63% of all absence seizures. However, the automatisms are less elaborate than those observed with complex partial seizures. There may also be autonomic manifestations, such as pupil dilation, flushing, tachycardia, piloerection, salivation, or urinary incontinence.

"Absence Seizures and Syndromes: An Overview", from Perspectives in Pediatric Neurology

So again we brace ourselves, not for that often-imagined moment when Schuyler falls to the floor in a grand mal seizure and suddenly It Has Come, but rather for the suspicion, the realization that something may already be happening, that the odds may have caught up with her at last. Last time, we wondered because Schuyler had been spacing out from time to time. This time, the signs are even more compelling. And again, we'll put Schuyler in the hands and the sensors of a neurology team in the hopes that they may have their crown of wires attached to her at an opportune moment so that we can finally know if this is beginning in earnest.

Schuyler is eleven now, and we believe that she's old enough for a little more adult conversation about this. She's known about her condition for a while. A number of people have written to me over the years, afraid that words like "broken" and "monster" were going to scar her somehow, but the fact is that we've had some version of this conversation going with her all along. People afraid of how Schuyler might feel if she read my words one day are missing the point. She's been hearing the words, she's been soaking up the concept. Hiding her reality from her would be wrong, and it would be pointless. She faces the big truths in her own way; she processes them in her own time.

She was feeling humiliated by her accident tonight, as she had the night before, so I sat down with her and explained that these accidents might not be her fault. I told her that the same thing in her brain that makes it hard for her to speak clearly, the thing that causes her to drool sometimes and keeps her from eating some foods, that thing might also be causing her to pee her pants every now and then. I explained how our brains run on electricity (which she thought was pretty cool), and that some brains use too much electricity sometimes, which causes them to overload. Those overloads are called seizures, I told her. Some of them are brief and small, so small that the person doesn't know that they had them, while others are bigger.

I told her that we will have to see a doctor again to be sure, but that she might be having those little seizures, and if she is, that might be causing her to pee her pants. I told her that these seizures were cause by the thing in her brain that made her different.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"What's what called?"

She pointed to her head. "The little monster in my brain."

It occurred to me that I might not have ever actually told her this part. "It's got a long name, it's called polymicrogyria."

She thought about that for a moment, and then laughed. "That's a funny name," she said.

"Do you want to call it something else?" I asked.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"Polymicrogyria."

She laughed. "I know, I know!" (She says "I know, I know!" a lot when she gets excited.) "It's Polly the Monster!"

I see a monster that may finally be giving my little girl seizures, might be delivering on the ugly promise we'd been made when Schuyler was diagnosed almost eight years ago, and I feel my heart drop again.

Schuyler sees that monster, and she nicknames it Polly.

As we drove to pick up Julie at work, Schuyler sat quietly in the passenger seat, processing. Finally she turned to me.

"Daddy? I don't want a little monster in my brain."

She said it seriously but not somberly, sad but not crushed. I told her that I didn't want her to have it, either, but there was nothing we could do but make the very best of it, the same as we always had.

She shrugged a little and said, "I know."

Later, she asked Julie if she was sad. She said it with concern for her mother, but I didn't get the sense that she was terribly sad herself. I mean, she wasn't thrilled by this new situation, but she was processing it already, moving faster than we were, perhaps sensing that some very hard stuff may be waiting in the near future but already impatient with the sad.

"I know." She knows.

February 15, 2011

Helicopters

There's been a recurring theme recently in disability blogs and other online forums. Writers, mostly parents, are making lists of "Things You Shouldn't Say to Parents of Kids with Disabilities". I'm not usually a joiner in this sort of thing, but the other day I realized that apparently I do have something to contribute to these lists.

We met the band director at Schuyler's new middle school, and it went pretty well. She didn't roll her eyes at us, she seemed genuinely interested in learning more about Schuyler and was very willing to set up a meeting with us. It was a very promising start. This band thing has the potential to really make a difference in Schuyler's life, so we are taking it very seriously. We were looking forward to attending the demonstration concert with Schuyler and her class this week until we received a note from the elementary school music teacher who is organizing Schuyler's school's part of this trip. In the middle of the note (sent home to everyone, I should add, not just us), it said simply "Due to limited space, parents are not invited to attend."

I'm not sure if it was the way the note was worded or our past experience with previous schools where parents weren't encouraged to attend classroom events. But something about that note made us dig in our heels a bit. And when I wrote to the teacher and explained why we felt it was important and appropriate for us to be there, her reply demonstrated a certain amount of dug in heels as well. The field trip is on Wednesday; perhaps I will have stories to share with you then. We are planning to attend and have informed the school of this. So there you go.

Now, this isn't a story about why this is or isn't an appropriate position for us to take. I'm sure I'll hear from some of you anyway, but I'm pretty solid with this. I think that with the exception of tests being administered or the like, any school function should be open to attendance by interested parents. That's just a given to me. Saying that there's limited space is frankly just weak.

No, this is a story about me writing a short note about this on Facebook and having someone respond that the schools wisely limit parent involvement to these things because of "helicopter parents" who hover and try to influence their kids and interfere with their independence. It was then that I mentally caught something that had tweaked me for years but I was only now able to identify. It became my "Thing Not to Say to the Parents of a Special Needs Kid."

The term "helicopter parents" is meaningless, inappropriate and insulting to parents of kids with disabilities. Don't say it to us. Don't even think it about us. Save it for Toddlers & Tiaras.

As parents of special needs kids, we hover because integration into school programs like band is incredibly important to our children. It is the thing that can release them from the gentle ghetto of special education classes that can become their parking place until they are old enough for the public schools to relinquish responsibility and return them to "Your Problem" status. We hover because we've seen what happens when we don't. We've seen what happens in even the best programs when a child is difficult to teach and no one is looking. We hover because we can remember past schools in past towns where our child was forgotten in the corner because she was a broken child, but a polite and quietly broken one who didn't require constant attention and protection. We hover, not because we don't want our kids to become independent, but because we desperately want them to be, and we know the paths that are most likely to lead them there. We hover because history has shown all of us that if we don't watch out for our kids, sometimes they don't get watched out for.

We don't just hover. We monitor, we observe, we interfere when necessary, and we educate ourselves so that we are able to identify those times when it becomes necessary. Our complete and total involvement with our kids' school experience is not negotiable. Special needs parents are experts in the one thing that even the best schools will never master. We know our kids. More to the point, we know their monsters. And if we believe that we need more information on how a program works or how it is going to affect our child, it is inappropriate to tell us that we're not invited, we're not needed, they've got a handle on this, there's nothing for us to worry about.

Are we a pain in the ass to the schools where Schuyler has attended? If we are, then it's because someone has forgotten that we are part of her team. Someone has let themselves be fooled into thinking that they know what's best for her and that she is like any other kid they've taught. Any time a teacher thinks that past experience tells them all they need to know about teaching a child, they have already failed. This is true of any student, but it is true a hundred times over for a child with a disability. Every broken child is broken in their own way. Every single one of them.

So special needs parents become helicopter moms and dads, if that's how you want to look at it. But if that's how you see us, I hope that you'll keep that opinion to yourself. Unless you are one of our kids' teachers. In that case, I hope you will keep that opinion to yourself, AND get the hell out of the way.

February 11, 2011

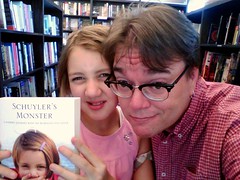

Pimpage

Both this blog and my book have made it to the finals of the About.com Readers' Choice Awards. It would be extra super swell if you'd go vote. You can do so once a day, every day through March 8. The winners will be announced on March 15.

Thank you kindly for your support, yo.

February 6, 2011

January 30, 2011

“Is it better to out-monster the monster or to be quietly devoured?”

I got a reasonable, respectfully worded comment (God, how refreshing) regarding my terminology which I felt deserved an equally reasonable and respectfully response. By the time I was finished, it had gotten far too long for a comment. And while I've written about this before, at length, it's an important point and probably deserves to be revisited from time to time. I felt like it certainly deserved its own post. So here we go...

---

Of course you are entitled to your opinion and your disagreement, and I thank you for posting. A few thoughts:

You're absolutely right, there is no predicting how Schuyler will feel about anything I've written about her and her condition. That point has been made in countless "How is she going to feel one day when she reads...?" posts and emails and criticisms. It's a valid point. You have to remember, however, that our feelings and opinions and reactions to Schuyler's situation aren't happening in a vacuum. I'm not writing one thing and saying another to her. From the very beginning, she has been raised to understand that no, she's not like other kids and yes, she has to work hard to overcome the obstacles that are in her way.

Schuyler knows that there's something wrong with her brain, she understands better than you or me or anyone else how true that is. She may choose to see it differently as she gets older, but she'll make that determination on her own. And she'll do so knowing that her parents love her and are inspired by her. The idea that she will one day read something I wrote and suddenly she'll know some dark secret about how I visualized her disorder is absurd. She already knows what the title of the book refers to; it was her metaphor originally, after all. We don't keep anything from her regarding her condition. THAT would be offensive, wildly so. Schuyler's not a delicate flower. She's a tough kid, because she has to be, and she's also a realistic one.

People acting out of concern for Schuyler are certainly within their rights to do so. Concern that she will be somehow wounded by an acknowledgement of her very real, very hard condition is frankly insulting to her, though. It sells her short. It denies her very real ability to face her condition head on.

"I do feel it is important to hear the experiences and opinions of adults who have grown up with disabilities or differences (whatever they may be). I think theirs is the most relevant voice in this debate."

Their voices are both absolutely relevant, and at the same time completely beside the point. I hope you don't think that after all this time, I haven't been listening to the opinions of persons with disabilities, along with their families and caregivers. But the thing you might not understand is that if I've heard from a hundred people, I've heard about a hundred different opinions and perspectives. There is no consensus. Well, of course there isn't.

For every person who is inspired by the Holland poem, there are equal numbers who find it to be condescending and ridiculous. For every person who depends on their faith in God to sustain them, there's an equal number who feel like that God has turned his back on their loved ones, or who have lost their faith altogether. For every person with a disability who finds comfort in People First Language, there are equal numbers who self-identify with terms like "cripple". Which of these voices should dictate how my family and I deal with Schuyler's disability?

"I personally disagree with your use of the term "monster" to describe something that your child cannot separate from herself. This goes against every instinct I have. I am an educator but not a parent."

I think this is an important point. I respect that my philosophy goes against your instincts. I am going to have to insist, however, that you likewise respect the fact that those educator's instincts are very different from those of a parent, particularly if you don't have children of your own. And I don't mean to condescend, either. But no matter how dedicated of an educator you may be, no matter how much time and energy and personal emotional investment you put into your work with our kids, there is a very real difference between our worlds.

You get to go home at the end of the day. You get to watch our kids grow older and leave your care. No matter how challenging or how impressive our kids' disabilities may seem to you, the fact remains that we live with them in ways that you simply don't. From the moment our kids' disabilities revealed themselves to us, entirely unanticipated, we live with the reality of those disabilities every minute of every day, and not for a year, or a few years, but for the rest of our lives. We don't just worry about whether our kids are going to successfully complete the school year. If our kids survive their hard childhoods, we then get to wonder who is going to take care of them when we die.

I hope you'll understand how something that is a part of our beloved, beautiful child can still be monstrous, for her and for me. In the end, Schuyler will come to her own conclusions about that word and about her condition. But she won't be surprised, and I seriously doubt she'll be offended. I don't give Schuyler sugar-coating or soft language. I will always give her love, and the truth. Those may actually be the two most valuable things that I have for her.

---

"I personally disagree with your use of the term "monster" to describe something that your child cannot separate from herself. This goes against every instinct I have. I am an educator but not a parent.

"I don't think most people (with the always exceptional minority of crazies) would argue this point with you out of spite or with the goal of proving you wrong but rather out of concern for your daughter and a hope that sharing one's own experience can make a difference in the life of another child and family going through a familiar struggle.

"However, there is no point arguing about it as only time will tell how your daughter will feel about it. I do feel it is important to hear the experiences and opinions of adults who have grown up with disabilities or differences (whatever they may be). I think theirs is the most relevant voice in this debate."

Of course you are entitled to your opinion and your disagreement, and I thank you for posting. A few thoughts:

You're absolutely right, there is no predicting how Schuyler will feel about anything I've written about her and her condition. That point has been made in countless "How is she going to feel one day when she reads...?" posts and emails and criticisms. It's a valid point. You have to remember, however, that our feelings and opinions and reactions to Schuyler's situation aren't happening in a vacuum. I'm not writing one thing and saying another to her. From the very beginning, she has been raised to understand that no, she's not like other kids and yes, she has to work hard to overcome the obstacles that are in her way.

Schuyler knows that there's something wrong with her brain, she understands better than you or me or anyone else how true that is. She may choose to see it differently as she gets older, but she'll make that determination on her own. And she'll do so knowing that her parents love her and are inspired by her. The idea that she will one day read something I wrote and suddenly she'll know some dark secret about how I visualized her disorder is absurd. She already knows what the title of the book refers to; it was her metaphor originally, after all. We don't keep anything from her regarding her condition. THAT would be offensive, wildly so. Schuyler's not a delicate flower. She's a tough kid, because she has to be, and she's also a realistic one.

People acting out of concern for Schuyler are certainly within their rights to do so. Concern that she will be somehow wounded by an acknowledgement of her very real, very hard condition is frankly insulting to her, though. It sells her short. It denies her very real ability to face her condition head on.

"I do feel it is important to hear the experiences and opinions of adults who have grown up with disabilities or differences (whatever they may be). I think theirs is the most relevant voice in this debate."

Their voices are both absolutely relevant, and at the same time completely beside the point. I hope you don't think that after all this time, I haven't been listening to the opinions of persons with disabilities, along with their families and caregivers. But the thing you might not understand is that if I've heard from a hundred people, I've heard about a hundred different opinions and perspectives. There is no consensus. Well, of course there isn't.

For every person who is inspired by the Holland poem, there are equal numbers who find it to be condescending and ridiculous. For every person who depends on their faith in God to sustain them, there's an equal number who feel like that God has turned his back on their loved ones, or who have lost their faith altogether. For every person with a disability who finds comfort in People First Language, there are equal numbers who self-identify with terms like "cripple". Which of these voices should dictate how my family and I deal with Schuyler's disability?

"I personally disagree with your use of the term "monster" to describe something that your child cannot separate from herself. This goes against every instinct I have. I am an educator but not a parent."

I think this is an important point. I respect that my philosophy goes against your instincts. I am going to have to insist, however, that you likewise respect the fact that those educator's instincts are very different from those of a parent, particularly if you don't have children of your own. And I don't mean to condescend, either. But no matter how dedicated of an educator you may be, no matter how much time and energy and personal emotional investment you put into your work with our kids, there is a very real difference between our worlds.

You get to go home at the end of the day. You get to watch our kids grow older and leave your care. No matter how challenging or how impressive our kids' disabilities may seem to you, the fact remains that we live with them in ways that you simply don't. From the moment our kids' disabilities revealed themselves to us, entirely unanticipated, we live with the reality of those disabilities every minute of every day, and not for a year, or a few years, but for the rest of our lives. We don't just worry about whether our kids are going to successfully complete the school year. If our kids survive their hard childhoods, we then get to wonder who is going to take care of them when we die.

I hope you'll understand how something that is a part of our beloved, beautiful child can still be monstrous, for her and for me. In the end, Schuyler will come to her own conclusions about that word and about her condition. But she won't be surprised, and I seriously doubt she'll be offended. I don't give Schuyler sugar-coating or soft language. I will always give her love, and the truth. Those may actually be the two most valuable things that I have for her.

January 21, 2011

"Beneath those stars is a universe of gliding monsters."

"...Heaven have mercy on us all - Presbyterians and Pagans alike - for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending." -- Melville (Moby-Dick)

-----

(Note to parents of kids with polymicrogyria: While I'm not normally one who worries a great deal about so-called "triggers", and while I'm writing this in large part on your behalf, I nevertheless feel like I should give you a heads up that I'm going to be talking about stuff that you are all-too-aware of but might not particularly enjoy reading about.)

I know I recently pledged to focus on the positive, and this post might not seem to honor that. But I actually think it does, because I believe clarity and respect are positive attributes, and I need to speak about those topics today.

I received a comment on this blog recently, from someone who has left critical comments before, and that's fine. I've posted them in the past because I really don't believe that it serves anyone, least of all me, to sanitize the comments left here. I've mentioned before that I will reject a comment if it is threatening or disparages anyone besides myself, or if it is clearly part of a coordinated campaign to dump on me for whatever reason. I think my comments become boring if they're all "go Rob" or "me too". But this comment I ultimately decided not to publish, because I felt like it could be offensive or hurtful to other family members of persons suffering from polymicrogyria, aka "Schuyler's monster".

But the remark stayed with me, if only because it's not even remotely the first time I've been confronted by the idea it contained. If I thought it represented one crank's opinion, then I would let it go. But the fact is, it doesn't, not by a long shot. So I guess I've changed my mind about posting it.

"What will become of your life when Schuyler's monster becomes her identity? Maybe she will grow to resent that you call what makes her a unique individual a 'monster' as if were a bad thing."Like I said, the idea of Schuyler's polymicrogyria as a kind of unique personality trait rather than a serious and potentially dangerous affliction is hardly a new one. And I'm sure that I've made it even easier to make that claim. I recently said the following, after all:

Schuyler's polymicrogyria isn't her greatest challenge, not any more. Her life doesn't seem to be in any real danger, with no apparent seizures yet, and her monster doesn't impede her everyday life with the ferocity that it does for so many other PMG kids. For that, I am grateful.I further explained that Schuyler's difference, her uniqueness, is something that I'm still thrilled by, and I consider it my distinct honor to be the person who gets to help lead her through a world that might not understand her difference, but which is nevertheless a much better, more vibrant place because of it.

So let me make this as clear as I can. I love Schuyler wildly, and I find her to be fascinating. I think she is by far the most interesting person I've ever known, and she's only eleven. And while I acknowledge that a huge part of that comes from the fact that I am her father, I am also aware that my fascination with the strange and wonderful person she is stems in no small part to the fact that I get to see into her unique world more than most people, more than anyone with the exception of Julie.

I think I've made that pretty clear in the past, in what, like 90% of what I write?

Here's the other thing, however. If I could have a chance to experience life with a Schuyler who was born free of her polymicrogyria, if I could go back in time and spend the past eleven years with a neurotypical version of Schuyler, I would do it in a heartbeat.

Because here's the thing that a statement like "you call what makes her a unique individual a 'monster' as if were a bad thing" is sugarcoating:

Polymicrogyria is a bad thing.

Polymicrogyria, in its many forms, affects the lives of its victims in various ways, and all of them are bad things. The difficulties with swallowing that consign some PMG kids to a lifetime of liquified foods and bouts with choking and life-threatening pneumonia are bad things. The lack of speech that robs PMG patients of significant early communication and stunts their development both intellectually and socially for the rest of their lives, that is a bad thing. The accompanying cerebral palsy that many patients experience, the difficulty in walking, that is a bad thing. The cognitive issues that can range from a developmental delay to severe intellectual disability, those issues are very bad things indeed, no matter how you spin them.

And the seizures, the ones that Schuyler is still in danger of developing, those terrifying episodes that strike some PMG patients at birth, those powerful electrical hurricanes swirling in those young, innocent brains that rob many very young polymicrogyria patients of their very lives before they reach their first birthdays, those are very very bad things. I follow polymicrogyria discussion boards, I see the notices that some young person has been killed by that thing that makes these kids such "unique individuals". I haven't experienced the pain that so many polymicrogyria families and those who battle other similar disorders like microcephaly and Angelman Syndrome have gone through, but I've witnessed the devastation that many of them endure.

And I never let myself forget, because it would be a crime of hubris to do so, that at any time, especially now as Schuyler's body and brain begin to undergo a whole new world of changes, our own world could be rocked, and that Schuyler's monster could grow some very big teeth.

So yeah. I feel comfortable calling it a monster, and while I celebrate Schuyler's individuality and always will, I also recognize that it has come with a price, one that she pays and will continue to pay all by herself. And I call it unfair, because it IS unfair, that she will not have the opportunity to choose her own individuality, her own path, without the unfeeling hand of that monster writing much of her narrative for her.

I understand how many people in the disability community choose to embrace disability rather than fight it. I get the Holland poem, and I understand that it means a lot to many people, even if I reject it. But I do reject it, as I reject the embrace of disability as just another thing that makes our kids and our loved ones who they are. It feels wrong to me, almost like a kind of fetishization of disease or disability.

I am not moved either way if you feel that way about your own afflicted family or your own disability. Everyone makes their own way as best as they can, and I respect that. But I find it offensive if you suggest that I should do the same, and that I should embrace the thing that, yes, breaks my child and which torments so many of her neuro-atypical brothers and sisters with such ferocity. It is a bad thing, as far as I am concerned, and I will call it a monster.

I started using the monster metaphor (stolen from Schuyler, if I'm being honest) long before I wrote a memoir, but it wasn't until an interviewer asked me about it during the press attention that the book generated after its release that I gave it much thought. I realized that it was a metaphor that I embraced, not for literary purposes but for personal ones. Like Schuyler, I needed to imagine polymicrogyria as a monster, because I can't fight a little girl's broken brain. But I can fight a monster. I can imagine myself going into battle against one of those.

And I don't even envision that fight as something heroic, either. Maybe I did, in the beginning, but not now. I'm not Perseus, heroically outsmarting and killing archaic beasts. I'm not St. George slaying the dragon.

If anything, I am more like Captain Ahab, fighting obsessively against a monster that I can never defeat. Like Ahab, I am aware of the futility, but I am also unable to turn away.

Schuyler's affliction, the one that hurts and kills other children, the one that touches her more gently than some but still colors her life so completely, it is a monster. If someone comes here to try to make a case that it's not, and that it is simply one of the innocent, beautiful little parts of her personality that make her the purple snowflake that she is, they should do so knowing that I will disagree, and I will find their disrespect for this bad thing to be offensive.

Melville's description of the sea ("...this velvet paw but conceals a remorseless fang") works pretty well for Schuyler's manifestation of polymicrogyria. It's not cute. It makes Schuyler's life hard, and moreover it devastates and even takes away the lives of others. I'm with Ahab on this one. I'll never quit.

Thus, I give up the spear.

January 19, 2011

"Hear angel trumpets and devil trombones..."

All parents have a narrative for their children. Some are blatant and perhaps a little horrible, like the ones on a television show that Julie and I have recently become addicted to, about the parents of kids who play sports and who live out their own past failures or glory days through their own children. The rest of us watch them and say, "How awful!" and "My little girl is going to chart her own course, she’ll decide what her future's going to be all about, not me." But in our secret hearts, we whisper, "I hope she plays the trombone...." (No, I really do. I suspect Julie's secret heart and mine are whispering different things.)

-- excerpt from Schuyler's Monster

I'm not usually so prescient...

The photographic evidence is a little misleading, I hasten to add here. Schuyler is not in fact playing the trombone, and I am realistic enough to admit that we might be over-reaching, or at the very least reaching in the wrong direction. But we're giving it a try.

In a few weeks, Schuyler and the rest of her fifth grade class will pile on buses and travel the roughly five hundred feet to the middle school (which sits on the other side of a soccer field from her elementary school) for their introduction to the middle school music programs.

(Note to school: When you're done putting the kids on the bus, perhaps after feeding them fried burritos, go to your office and Google "childhood obesity".)

(Note to readers, regarding my own raging hypocrisy and delivered in a Homer Simpson voice: Mmmmmmm. Fried burritos. Do they even serve those to kids anymore? Do I have to drive to a rural gas station to find one?)

But I digress.

Being the busybody parents that we are, Julie and I will be attending this field trip. Schuyler will be introduced to the music ensemble programs, including the orchestra and choir, both of which are areas poorly suited for her particular monster-affected abilities. String instruments require a level of finger dexterity that she would find extremely frustrating.

And choir? Well, yeah. Moving on.

Schuyler will also be visiting the band program, and this is an area where we think she just might find some possibilities. A couple of months ago, Schuyler and I drove down to San Antonio to visit with two of my closest friends. (You might remember the last time we went to visit them.) Jim is a band director, and an excellent one at that, at a high school in the area, and Kimberly directs the color guard for his program. We spent the day doing band stuff. I taught the trombones a master class in the morning (don't laugh, haters), and then we accompanied the band to a marching competition, followed by a football game that evening.

Schuyler had a fantastic time. She bonded with members of the color guard, referring to them as her sisters (she's actually stayed in touch with one of them via email), and she made friends with a young lady who played the tuba, which planted in Schuyler's head the fun (and appropriately Schuyler-weird) idea of playing the tuba one day. We carefully noted how the kids responded to Schuyler, and how lasting her impression of that day has been. The experience made us realize that beyond our own musical aspirations for Schuyler, which may or may not be reasonable, joining the band could very well provide Schuyler with a whole level of support, protection and most of all acceptance far beyond what she is likely to find amongst the general student population.

It's tricky, though, for a few reasons. For Schuyler, there are physical limitations from her polymicrogyria that present some daunting challenges. Her limited finger dexterity probably rules out woodwind instruments, for example, as does the issue she has with weak facial muscle tone. But that very weakness might also benefit from the techniques required to build a brass embouchure, and the trombone requires hand and wrist coordination, but not so much fingers. Her weak facial muscles probably rule out trumpet or horn, but tuba or trombone might be workable.

And I can teach those instruments to her. She already has a trombone. And Julie has a degree in music. If it works out, it feels like a natural fit.

Less within our control is the band program itself. I have, in my years as a trombonist, performed with a great many conductors. I've worked with and known some amazing directors who inspire me to this day, but I've also worked with some, well, you know. There's an old joke that sums up the rare but memorable experiences that many of us had from time to time. ("What's the difference between a bull and an orchestra? On a bull, the horns are in the front and the asshole is in the back.") As far as public school band directors go, there are a lot of them, I'd say most of them in fact, who love working with kids and who take their work as educators extremely seriously. But it's always that nasty handful, the ones who mostly cared about winning competitions and impressing their peers at the expense of students who needed more help, that former band nerds tell stories about years later. A great band director can change a kid's life; I had several who did just that for me. But the opposite is true as well.

I have no idea how Plano will shake out in this regard. The Plano schools are deeply committed to their special education students. And the Plano bands are extremely competitive. It really could go either way.

It's early to worry about that sort of thing now, though. For the time being, Schuyler is trying the trombone, contemplating her choices (percussion is high on her list as well), and dreaming of joining her sisters in the color guard.

As for me, I'm just imagining Schuyler surrounded by people who care for her and who would fiercely defend and encourage her. Because if there is one thing I've seen consistently from band kids, it is how they treat their peers with disabilities. It might be that band doesn't ultimately work out for Schuyler. But I can't tell you how much I hope it does, for reasons that mostly have very little to do with music.

January 10, 2011

Style Monster

One of the enduring mysteries of Schuyler is also one of the most interesting, and least quantifiable. How does Schuyler see herself? The little peeks through the curtains that we get from time to time show a little girl who simultaneously wants to be like every other little girl her age and yet is deeply in touch with her own beautiful strangeness.

Over the weekend, before the Wall of Wintery Death descended on North Texas (it is admittedly a short wall, but still), Schuyler asked me to take pictures of her. In eleven years on this planet, I do think this might actually be the first time she's ever done this. I've taken literally thousands of photographs of Schuyler, but her attitude toward me and my camera have always been ambivalent at best. One day she'll learn how to get a restraining order against me, and that will be that.

But this weekend, she wanted me to take photographs of her, and she had a very specific look that she wanted to capture, including the green wig resulting from her love of a character in the movie Scott Pilgrim vs. The World and the fingerless skater gloves that have become an indispensable part of her wardrobe. This was the look she wanted to capture, and I'll be damned if she didn't look awesome. Rather odd, and rather cool.

Schuyler had to make a college logo banner for school, for an assignment tying in with "College Week". (I'd make a remark about Plano parents already worrying about college for their fifth graders, except I suspect that is now the norm everywhere. Back in the day, I started worrying about college about halfway through my senior year, but that was probably a lack of planning and ambition all my own.) Schuyler hasn't had much interest in college, aside from the campuses where she has appeared for conferences like Vanderbilt and Auburn, so we had to explain some possibilities to her.

She eventually chose Yale ("because they helped me with my brain"), but she also decided, out of nowhere, that she wanted to go to school in China, because "it would be fun!" It was hard to argue with her logic, and she never wavered from this great idea, even after I told her that she might end up working in a factory making plastic Spongebobs for Happy Meals. She is immune to my cynicism.

Schuyler is building a very interesting and diverse self-image, one that emerges in her art and her stories and, I think most of all, in the dreams that she describes to us. It is, as it has been from the beginning, a view of herself constructed equally out of parts of this world and her own. We have a game we play now sometimes called "Real or Pretend", where I name something and she tells me whether it's real or imaginary, and her answers are surprisingly pragmatic. I was surprised to hear "pretend" when I mentioned mermaids and dragons and zombies and vampires (four of her favorites). She was delighted to learn that dinosaurs WEREN'T pretend, except when they are shown walking around in the modern world. But some of her answers were exactly what I expected, and secretly hoped for. Santa is real. Fairies are real. King Kong is definitely real.

The piece that fascinates me the most is how Schuyler incorporates her disability into her self-image. She's always identified with Ariel from The Little Mermaid, perhaps unsurprisingly; when asked why she loves this character so much, Schuyler touches her throat and then mimes the throwing away of her voice. But it's hard to know sometimes how much she wants to acknowledge her monster. She's reached a stage in her life when she doesn't want to use her speech device any more than she absolutely needs to, and when she does, she often insists on spelling out her words rather than using the icon sets.

But then she'll surprise us. The other day, while walking through a store, Schuyler saw a piece of pop art that she insisted she wanted for her room. When asked why, she mimed her wordlessness again. The art wasn't about being unable to speak. It wasn't an artistic treatise on mutism, not at all. But that was how Schuyler interpreted it, and now that it's hanging in her room, she goes back to look at it over and over. She seems very pleased with it, and with her own interpretation of its significance.

Schuyler is smart enough, and pragmatic enough, to understand that her disability is an integral part of who she is, and every now and then, she takes total ownership over it. But like everything else, she does it with style. Her own weird, wonderful style.

Over the weekend, before the Wall of Wintery Death descended on North Texas (it is admittedly a short wall, but still), Schuyler asked me to take pictures of her. In eleven years on this planet, I do think this might actually be the first time she's ever done this. I've taken literally thousands of photographs of Schuyler, but her attitude toward me and my camera have always been ambivalent at best. One day she'll learn how to get a restraining order against me, and that will be that.

But this weekend, she wanted me to take photographs of her, and she had a very specific look that she wanted to capture, including the green wig resulting from her love of a character in the movie Scott Pilgrim vs. The World and the fingerless skater gloves that have become an indispensable part of her wardrobe. This was the look she wanted to capture, and I'll be damned if she didn't look awesome. Rather odd, and rather cool.

Schuyler had to make a college logo banner for school, for an assignment tying in with "College Week". (I'd make a remark about Plano parents already worrying about college for their fifth graders, except I suspect that is now the norm everywhere. Back in the day, I started worrying about college about halfway through my senior year, but that was probably a lack of planning and ambition all my own.) Schuyler hasn't had much interest in college, aside from the campuses where she has appeared for conferences like Vanderbilt and Auburn, so we had to explain some possibilities to her.

She eventually chose Yale ("because they helped me with my brain"), but she also decided, out of nowhere, that she wanted to go to school in China, because "it would be fun!" It was hard to argue with her logic, and she never wavered from this great idea, even after I told her that she might end up working in a factory making plastic Spongebobs for Happy Meals. She is immune to my cynicism.

Schuyler is building a very interesting and diverse self-image, one that emerges in her art and her stories and, I think most of all, in the dreams that she describes to us. It is, as it has been from the beginning, a view of herself constructed equally out of parts of this world and her own. We have a game we play now sometimes called "Real or Pretend", where I name something and she tells me whether it's real or imaginary, and her answers are surprisingly pragmatic. I was surprised to hear "pretend" when I mentioned mermaids and dragons and zombies and vampires (four of her favorites). She was delighted to learn that dinosaurs WEREN'T pretend, except when they are shown walking around in the modern world. But some of her answers were exactly what I expected, and secretly hoped for. Santa is real. Fairies are real. King Kong is definitely real.

The piece that fascinates me the most is how Schuyler incorporates her disability into her self-image. She's always identified with Ariel from The Little Mermaid, perhaps unsurprisingly; when asked why she loves this character so much, Schuyler touches her throat and then mimes the throwing away of her voice. But it's hard to know sometimes how much she wants to acknowledge her monster. She's reached a stage in her life when she doesn't want to use her speech device any more than she absolutely needs to, and when she does, she often insists on spelling out her words rather than using the icon sets.

But then she'll surprise us. The other day, while walking through a store, Schuyler saw a piece of pop art that she insisted she wanted for her room. When asked why, she mimed her wordlessness again. The art wasn't about being unable to speak. It wasn't an artistic treatise on mutism, not at all. But that was how Schuyler interpreted it, and now that it's hanging in her room, she goes back to look at it over and over. She seems very pleased with it, and with her own interpretation of its significance.

Schuyler is smart enough, and pragmatic enough, to understand that her disability is an integral part of who she is, and every now and then, she takes total ownership over it. But like everything else, she does it with style. Her own weird, wonderful style.

January 7, 2011

My Year of Golden Bees

So, 2011. What have you got?

I'm not going to lie. 2010 was a rough year for us, in ways too numerous and depressing to list. For me personally, it was a year of things that I desperately wanted to work out ultimately NOT working out, in dramatic failures. For Schuyler, I suspect 2010 was even worse, a year in which her understanding of her own real differentness coincided with her classmates beginning to pull away from her and her strange, childlike ways. It was the year that I felt like her school might have begun to give up on her in some small ways, too. I'll always remember that 2010 was the year that we were asked to allow Schuyler's school to classify her as retarded.

I guess this year was the first time I realized that there are situations in which Schuyler attending school in a district with such a strong special education program might actually work against her from time to time. I have come to believe that there's a mindset that can take place in a strong program, one that suggests that they've seen it all before and know what will work for just about any kid, so if a kid is still difficult to reach, it must be because she simply CAN'T be reached. Schuyler is a very different kid, as I believe every special needs kid is wildly and perhaps sometimes tragically individualistic. Subsequently, I believe it's a mistake for any professional educator or therapist (or parent, for that matter) to believe that the past is always going to inform the present.

But I'm not a professional teacher. I'm a parent, and if I'm once again overbelieving in Schuyler, it is right and appropriate for me to do so. I don't think 2011 is going to see any change there.

It's hard, because one thing has truly changed this past year. Schuyler has a wish, although I'm not sure it's one that she would ever put directly into words, and it is the one thing that she can probably never have. Schuyler wants to be like everyone else. She wants to fit into a grey world of interchangeable children where no one strains to understand her. She wants to choose and build her weirdness for herself. The fact that she is unique in the whole world is not a very very special fact that thrills her now.

It still thrills me, though. It scares me and it haunts me, true, but it also thrills me. Most of all it makes me grateful that I am the one who gets to be her father and her guide in a world that doesn't exactly know what to do with a little girl like Schuyler and her monster. It's a full-time job, it's what I am supposed to do, it's who I am supposed to be, and while it precludes a lot of other things that I can't do or be because of it, it also makes me unique in the whole world, too.

Schuyler's polymicrogyria isn't her greatest challenge, not any more. Her life doesn't seem to be in any real danger, with no apparent seizures yet, and her monster doesn't impede her everyday life with the ferocity that it does for so many other PMG kids. For that, I am grateful.

Schuyler's challenges in this world, every last one of them, now involve her attempts and the attempts of her family and teachers and therapists to integrate her into our world. She doesn't fit, not entirely and sometimes not even mostly, but it is required for her to fit, so we struggle to make that happen. I am not at all sure, I am in fact entirely UNsure, that we are doing her a service by even trying, but there aren't viable alternatives and so we do it. I get the sense that this year will be a crucial one in this questionable but necessary work.

For myself, 2011 must be a year of changes, and the aspects that I can control are the ones within myself. When I go back and read the things I wrote over the past year, I saw a subtle change. I've always been sarcastic, and I've always engaged in dark humor, but this year I think I saw real bitterness in my writing, and a real loss of hope. I need to let go of that, this year more than ever before, because Schuyler is going to need a positive father as she makes some very difficult transitions. I'm going to need to be ready to fight harder than before, and to help her navigate school with a whole new crop of teachers and a whole new set of preconceived notions about what a kid like Schuyler might be capable of.

I need to find my positive center and hold onto it. If you want to call that a New Year's resolution, then fine. That works for me. I will clean my emotional house. I will let go of the things in my life that have been bumming me out, I will simplify my existence, and I will face my failures unblinkingly and then let them fall behind me. I found a quote from a poem by Antonio Machado that I love, a few lines that speak to what I need to do:

More than anything else, 2011 is going to be about working to integrate Schuyler into this grey, mean, dumb world. But I need to make sure that I never lose sight of my greater challenge, which is to make this world, by force if necessary, a little bigger and a little more accommodating to her, too. Because I envision a universe that has a place for Schuyler, a world where she can be exactly who she is, and her fellow earthlings will watch her with wonder, and they will say "Holy fuck, that is an extraordinary person."

I like that world. It's the one I live in every day, and I need to remember how lucky I am to do so.

I'm not going to lie. 2010 was a rough year for us, in ways too numerous and depressing to list. For me personally, it was a year of things that I desperately wanted to work out ultimately NOT working out, in dramatic failures. For Schuyler, I suspect 2010 was even worse, a year in which her understanding of her own real differentness coincided with her classmates beginning to pull away from her and her strange, childlike ways. It was the year that I felt like her school might have begun to give up on her in some small ways, too. I'll always remember that 2010 was the year that we were asked to allow Schuyler's school to classify her as retarded.

I guess this year was the first time I realized that there are situations in which Schuyler attending school in a district with such a strong special education program might actually work against her from time to time. I have come to believe that there's a mindset that can take place in a strong program, one that suggests that they've seen it all before and know what will work for just about any kid, so if a kid is still difficult to reach, it must be because she simply CAN'T be reached. Schuyler is a very different kid, as I believe every special needs kid is wildly and perhaps sometimes tragically individualistic. Subsequently, I believe it's a mistake for any professional educator or therapist (or parent, for that matter) to believe that the past is always going to inform the present.

But I'm not a professional teacher. I'm a parent, and if I'm once again overbelieving in Schuyler, it is right and appropriate for me to do so. I don't think 2011 is going to see any change there.

It's hard, because one thing has truly changed this past year. Schuyler has a wish, although I'm not sure it's one that she would ever put directly into words, and it is the one thing that she can probably never have. Schuyler wants to be like everyone else. She wants to fit into a grey world of interchangeable children where no one strains to understand her. She wants to choose and build her weirdness for herself. The fact that she is unique in the whole world is not a very very special fact that thrills her now.

It still thrills me, though. It scares me and it haunts me, true, but it also thrills me. Most of all it makes me grateful that I am the one who gets to be her father and her guide in a world that doesn't exactly know what to do with a little girl like Schuyler and her monster. It's a full-time job, it's what I am supposed to do, it's who I am supposed to be, and while it precludes a lot of other things that I can't do or be because of it, it also makes me unique in the whole world, too.

Schuyler's polymicrogyria isn't her greatest challenge, not any more. Her life doesn't seem to be in any real danger, with no apparent seizures yet, and her monster doesn't impede her everyday life with the ferocity that it does for so many other PMG kids. For that, I am grateful.

Schuyler's challenges in this world, every last one of them, now involve her attempts and the attempts of her family and teachers and therapists to integrate her into our world. She doesn't fit, not entirely and sometimes not even mostly, but it is required for her to fit, so we struggle to make that happen. I am not at all sure, I am in fact entirely UNsure, that we are doing her a service by even trying, but there aren't viable alternatives and so we do it. I get the sense that this year will be a crucial one in this questionable but necessary work.

For myself, 2011 must be a year of changes, and the aspects that I can control are the ones within myself. When I go back and read the things I wrote over the past year, I saw a subtle change. I've always been sarcastic, and I've always engaged in dark humor, but this year I think I saw real bitterness in my writing, and a real loss of hope. I need to let go of that, this year more than ever before, because Schuyler is going to need a positive father as she makes some very difficult transitions. I'm going to need to be ready to fight harder than before, and to help her navigate school with a whole new crop of teachers and a whole new set of preconceived notions about what a kid like Schuyler might be capable of.

I need to find my positive center and hold onto it. If you want to call that a New Year's resolution, then fine. That works for me. I will clean my emotional house. I will let go of the things in my life that have been bumming me out, I will simplify my existence, and I will face my failures unblinkingly and then let them fall behind me. I found a quote from a poem by Antonio Machado that I love, a few lines that speak to what I need to do:

"Last night as I was sleeping, I dreamt -- marvelous error! -- that I had a beehive here inside my heart. And the golden bees were making white combs and sweet honey from my old failures."

I like that world. It's the one I live in every day, and I need to remember how lucky I am to do so.

December 24, 2010

December 21, 2010

December 20, 2010

Eleven

Schuyler wasn't due until January of 2000. When she was born two weeks early, we tossed out the middle name we had chosen (Helena, in honor of the grandmother I never met; we decided to save that name for a future daughter, but Fate and its monster had different plans) and instead chose Noelle, the feminine form of a French word meaning simply "Christmas".

For the past eleven years, Christmas and Schuyler have always been inextricably connected to me. We're not Christians, but we have our own miracle baby to celebrate this time of the year. (Let the indignant emails begin.) To me, Schuyler is Christmas.

Tomorrow is Schuyler's eleventh birthday, and while it's true that every year brings a level of surprise at how much she has grown, this year feels even more change-filled than usual. She seems more complex, more understanding of the world around her, particularly the rough and ugly parts of it. And yet, when I watch Schuyler move through that world, I can see a young lady who possesses a quiet sort of confidence, and a strength that surprises me sometimes.

Two days ago, Schuyler returned to the dentist to finish the root canal from a month ago. Once he got into the tooth, however, he realized that he couldn't finish it. Schuyler apparently has a weird tooth, and will require the services of an endodontist to finish the job. Ultimately, she had endured another morning in the dentist's chair and another root canal session for nothing. It was frustrating.

But here's the thing. She didn't care. She didn't cry at all, didn't fuss or resist, and she kept a cheerful disposition the whole time. (The gas might have helped in that regard; it turns out that nitrous oxide makes her extremely chatty, the irony of which does not escape me.) The next day, for her birthday, she got the thing she's been requesting for about two years now: pierced ears. When they punched through her earlobes, a dark expression crossed her face for a few moments, but when she looked in the mirror, she smiled broadly and that was that.

This is the person Schuyler is becoming. She's more aware than ever of the pain and the clouds in her life, but she's also acutely in touch with the moments of joy, the pieces of beauty that are lying around waiting to be picked up.

In watching Schuyler grow into this extraordinary person, I myself am changed. It's ridiculous to say that I 'm a better person because of her. I don't even know the person I would be without her. I would be less, much much less. I would be a smaller, more shallow human being, and I would walk through the world largely unaware of those beautiful pieces waiting to be discovered. I have Schuyler to thank for that.

Happy birthday, little girl.

December 13, 2010

A conversation I'm not sure I know how to have

Conversation in the car, earlier tonight.

And there's a whole conversation to be had after that, the one about how being different is hard, but it's also the thing that makes you special, etc., the whole "purple snowflake" thing.

But Schuyler doesn't always buy it, not entirely, and while she was able to put it behind her by the time she went to bed, I know that it sticks with her now, in ways it didn't before. And all the pep talks and all the Sesame Street sentiments in the world don't change the fact that for a little girl like Schuyler, self-aware and a week away from her eleventh birthday, being different just sucks.

I can (and did) tell her that everyone is different in their own way and that's okay, but she knows that she is very different indeed. And sometimes it is very much not okay.

Me: Are you okay?

Schuyler: Yeah.

Me: You seem like you're sad.

Schuyler, shrugging: A little.

Me: Why are you a little sad?

Schuyler: Two mean girls at school.

Me: What did they do?

Schuyler: They made fun of me. "You're stupid. We're not friends at all!"

Me: Oh no! Why did they say that?

Schuyler: They don't like me because I can't talk. I'm different.

Me: You are different, but that's not a bad thing, you know.

Schuyler: I don't want to be different anymore.

And there's a whole conversation to be had after that, the one about how being different is hard, but it's also the thing that makes you special, etc., the whole "purple snowflake" thing.

But Schuyler doesn't always buy it, not entirely, and while she was able to put it behind her by the time she went to bed, I know that it sticks with her now, in ways it didn't before. And all the pep talks and all the Sesame Street sentiments in the world don't change the fact that for a little girl like Schuyler, self-aware and a week away from her eleventh birthday, being different just sucks.

I can (and did) tell her that everyone is different in their own way and that's okay, but she knows that she is very different indeed. And sometimes it is very much not okay.

December 11, 2010

December 6, 2010

Letting Go

Schuyler is growing up so quickly, and while I know that's something that every parent feels, I'm not sure they all feel it with quite the fear that I do. Well, perhaps they do at that. In just a few weeks, Schuyler will turn eleven, although just typing that word feels wrong under my fingers. Eleven? That's impossible. Babies aren't eleven. Don't be stupid.

Becoming the young woman that she is to be one day means letting go of the little girl she has been, and that's difficult, for Schuyler and, I suppose, for me as well. Lately it seems like there's been too much change, too many pieces of a childhood to put away at one time, too many grownup truths to face at once. Some of those truths are especially hard for me, the ones about myself and my own shortcomings in particular. It hasn't been an easy time lately.

The day after Thanksgiving, and on my birthday even, Schuyler received a rude awakening into a part of adulthood that has been particularly troubling during my own life. Out of nowhere, she suddenly began to cry, and hard. She indicated that a tooth was bothering her, and pointed to a part of her mouth where one of her baby teeth had been signaling its intent to jump ship for some time. But when I looked in her mouth, I instantly identified the problem, not with the baby tooth but rather with the permanent molar behind it. My stomach tightened when I saw it.

About half the tooth was missing. I was looking at the tissue inside the tooth.

So it was that after a night of Tylenol and lots of tears and Orajel, Schuyler experienced her very first root canal. I have to say, she was a total champ about it. There were some tears, but nothing hysterical. I sat next to her while she had it done, holding her hand the whole time, and while I don't think she had a great time, she was surprisingly resilient about the whole thing. We even had some fun laughing and taking pictures as one side of her face stopped working. But yeah, a ten year-old getting an emergency root canal. There have been a lot of little-girl-growing-up experiences we've been bracing ourselves for. This one caught us completely by surprise.

That surprise has been reverberating, too. Even with dental insurance, the crown is going to cost us a lot, and we were still trying to figure out how to get caught up as it was. That tooth is going to make for some changes around here, that much is clear. In the short term, we're going to become a one car family for a while. I simply can't make payments on my stupidly excessive car and still purchase The World's Fanciest Tooth. So we face some new realities, ones that plenty of families face, and I'm sure we'll get through it okay.

There's a hard truth to face. I'm not providing for my daughter the way I should. I have a good job, one that I'm frankly lucky to have, but I don't make enough money and I don't see any prospects for making more any time soon. We've been living an existence where one bad medical emergency (like, say, an emergency root canal) could torpedo us. It was only a matter of time, I guess.

Anyway, we'll make it, because that's what people do when things get tough. But the whole thing has amplified that nagging feeling I have. No, I'm going to just say it. It's not a feeling, it's a fact, one that I've stated on a number of occasions.