It all started with an email from my brother, with a link, some quoted material, and a question.

"Do you remember this guy?"

I'm not going to quote it directly. After I contacted the poster, identified myself and asked if we might talk, I received a delightful message from the board administrator, reminding me in that all-too-familiar "master of my online turf" way that posts on his forum were protected by copyright and could not be used in my next book without permission.

I am actually aware of how that works, oddly enough. And yet, I was tempted to quote it here in its entirety just the same. I feel a certain amount of personal ownership over the information. Go read it yourself and see if you can figure out why.

If you can't go see that, or if it disappears for some reason (although I guess that might solve the whole copyright issue), here's a short paraphrase of the material, posted on an epilepsy support forum in a thread about personal heroes.

The poster, whom I'll call David since, well, that's his name, tells the story about the hard days he experienced in junior high school. In addition to his health issues, David didn't know anyone at his new school and got picked on a great deal. He was eventually taken under the wing of the ninth grade track coach, who made him the manager for the track team. David described this coach as a real friend. The coach taught him everything he needed to know about being a track manager, was patient with his mistakes, gave him advice and even paid for his meals on road trips. This coach, he said, "became my second father". David's story ends sadly, when the coach died halfway through the year. At the funeral, the coach's wife told David that her husband always spoke of him like a son, and made sure that the pastor talked about him during the eulogy. At the end of the year, David won an award for the student who had the most success in the ninth grade, thanks to the nomination of his track coach and surrogate father.

And that, he concluded, is why his personal hero is Coach Bobby Ray Hudson.

Well. I didn't see that coming.

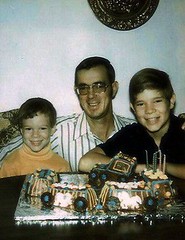

For the record, my answer to my brother's question was no, I didn't remember this guy, for a number of very good reasons. First of all, I was in college by this time. I hadn't seen my father in about four years; indeed, I wouldn't see him again until the funeral, which I don't suppose actually counts.

Furthermore, I didn't hear about my new little brother from my mother because she's not the wife that David is referring to. That would be the woman my dad married after he left my mom when I was in high school. None of us actually knew very much of what was going on in his life, because he had very intentionally and meticulously removed us all from his reality. After he died, we discovered just how true that was. His last will and testament stipulated that everything was to go to his new wife, which was hardly a surprise, but in the event that she did not survive him, everything would then go to her adult son, a police officer whom we didn't even meet until the the day before the funeral.

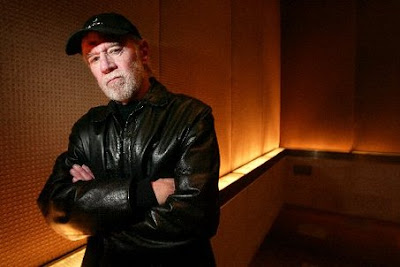

It's been eighteen years since my father died, and yet I find that he still has the power to confound me. After going to such great lengths to shed his family, why, at the very end of his life, did he suddenly feel compelled to be the kind of father that he never was before? Did he feel regret? A chance at some kind of redemption, but without the hard work it would have taken to make things right with us?

I never knew my father to be someone with a great deal of compassion, certainly not for the little six-year-old boy with whom he couldn't communicate except with the back of his hand. Had he found it at the end? I'd always wondered what my father would have thought of Schuyler. Judging from what I knew of him, I always suspected that he would have had a real problem dealing with a kid with a disability. Now? I'm not so sure. This chance encounter with a total stranger almost two decades after my father's death has changed everything.

I am acutely aware of the timing of this revelation, at a time when I am beginning work on a book about this very topic. Some writers search with great effort for their subjects. So far, mine seem to be finding me.

Schuyler is my weird and wonderful monster-slayer. Together we have many adventures.

August 27, 2008

August 20, 2008

Priorities

According to CNN, human rights organizations are reporting that more than 200,000 children were spanked or paddled in U.S. schools during the past year. My own state of Texas leads the pack, with 48,197 students. Well, of course it does.

Now, we can have the discussion about the morality and effectiveness of hitting kids if you like. I'm always ready for that topic, after all. I am very encouraged by the fact that the numbers are down, and that a number of states and school districts have outlawed corporal punishment altogether.

But one line in this report jumped out at me, hiding about halfway down.

In addition, special education students with mental or physical disabilities were more likely to receive corporal punishment, according to the ACLU and Human Rights Watch.

Even if you're one of the people who think that hitting a child is a good way to discipline and to educate, or perhaps especially if you believe that, I'd like you to stop for just a moment and think about that. I'd like for you to close your eyes and imagine how that scene might unfold.

Meanwhile, what's the topic of the most vocal outcry from disability advocates of late? The use of the word "retard" in a movie.

I don't know. To my thinking, those priorities seem sort of, well, you know. There's probably a word for it. I'm sure you can think of one.

Now, we can have the discussion about the morality and effectiveness of hitting kids if you like. I'm always ready for that topic, after all. I am very encouraged by the fact that the numbers are down, and that a number of states and school districts have outlawed corporal punishment altogether.

But one line in this report jumped out at me, hiding about halfway down.

In addition, special education students with mental or physical disabilities were more likely to receive corporal punishment, according to the ACLU and Human Rights Watch.

Even if you're one of the people who think that hitting a child is a good way to discipline and to educate, or perhaps especially if you believe that, I'd like you to stop for just a moment and think about that. I'd like for you to close your eyes and imagine how that scene might unfold.

Meanwhile, what's the topic of the most vocal outcry from disability advocates of late? The use of the word "retard" in a movie.

I don't know. To my thinking, those priorities seem sort of, well, you know. There's probably a word for it. I'm sure you can think of one.

August 19, 2008

Pet monsters are a lot of responsibility

Okay, so let's talk about People First Language.

I've seen it presented as a sort of universal truth, as if the rightness of People First Language is a given, with little room for argument. People First Language must be used, I read time and time again, like a moral imperative. The heartfelt and dedicated advocates of People First Language want very much for it to be accepted as a standard practice. Indeed, they often insist on it. But it's not universally accepted, although people who find it troubling are often nervous about discussing why. I'm a little nervous about writing this, to tell the truth, and we all know what an ass I can be.

The idea behind People First Language is simple, and inherent in the name of the concept. It puts the person first, allowing their basic existence to define them before their disability. People First Language describes what the person has, but not who that person is. By these rules, I am not a diabetic. I am a guy who has diabetes. The thinking behind People First Language says that identifying a person by their diagnosis can generate fear and pity, and works against the goal of inclusion. People First Language grants a person dignity, the thinking goes, by blunting the impact of their diagnosis on that person's self-image, and also in how they are perceived by the world.

"It's not 'political correctness,'" writes People First Language advocate Kathie Snow, "but good manners and respect."

Perhaps. I do see the point, and insofar as I think these kinds of perceptions are important issues, I can see some of the benefits of People First Language. I don't want Schuyler to be hurt by the world around her, and I certainly don't want her disability to make her feel like there's something wrong with her.

But here's the thing. As hard as it may be to admit this, there is something wrong with her. And admitting that she's broken on some level is difficult, and it feels harsh. But it's a harshness that comes from somewhere else, from whatever power you think hands out that kind of Very Special Gift. God if you believe in him, Fate if you don't, or just random shitty luck if that's how you roll. And the thing that it's easy to miss, because the idea breaks my heart too, is that no one is more aware of Schuyler's disability than Schuyler herself. When you think about it, that seems obvious, but for those of us who love her and care about her, it might be much easier to accept if we could adopt language that takes some of the sting out of her reality.

People First Language attempts to soften the language that we use to describe disability, and I understand why that's tempting. But in doing so, it doesn't blunt the monsters, not even a little. If you say, as People First Language instructs, that a paraplegic is NOT confined to a wheelchair or is NOT wheelchair-bound, but instead refer to them as "an individual who uses a wheelchair", you have taken away that wheelchair's power over that person in perception only. It even implies choice, at least in my opinion. I use things, and I use parts of myself, with intent. I don't think I'd say I use my heart, or my kidneys, because I am not given a choice, but I do use my legs. I choose to use them, and I can choose not to.

That sounds like I'm being obvious and glib, but it bothers me, and for some very real reasons. Because when you take away responsibility from the monster, who are you going to give it to? When you say that a person uses a wheelchair, you are setting up ownership of that disability. The monster doesn't have you. You have the monster.

But do we really want to hand ownership of that disability to a child who is struggling to understand their place in the world? Does handing responsibility for a disability over to the child give them an unreasonable sense of their own role in the possession of that disability? If you're using a wheelchair, then why not just stop? If that sounds silly to you, ask a now-grown child of divorced parents if they still, even if only in their secret hearts, take some measure of responsibility for their parents' breakup. Ask an adult with a disability if they ever wondered as kids what they did to deserve their situation. Ask them if they ever wonder that now.

If Schuyler isn't "non-verbal" but instead "communicates with an assistive technology device", then why? Why would she do that? If Schuyler doesn't feel like she is in the clutches of a monster to whom she brings the fight every day, that's great and my biggest dream made real. But if she then comes to the conclusion that she owns that lack of speech, then what can be the reason for its persistence? Is she not trying hard enough? Why isn't she fixing the issue herself? If she's not broken, then what's the problem? Lack of motivation? Is she simply not good enough? Not strong enough, or smart enough, or brave enough?

Schuyler as the victim (another word forbidden by People First Language) of Fate and its monster minion, as sad as that may sound, is infinitely preferable to Schuyler as the product of her own subtly-implied failure. I simply won't have it, any more than I'll have the idea of "acceptance" stand in the way of her hard work, and of ours. To my thinking, People First Language sets up an unreasonable expectation, taking the responsibility away from unfair forces at work in the world and instead laying it squarely at the feet of the very last people in the world who deserve to wonder if they somehow had this coming.

And don't even get me started on the ridiculous and unwieldy term "nondisabled" to describe neurotypical or "normal" people. That should offend anyone who loves the English language.

Listen. I get why people use People First Language. I understand the push to bring sensitivity to an often cold world. That's something I fight for as much as anyone else, after all. I wrote an entire goddamn book about it. But please try to understand, people. Don't just try to make it feel better. Don't blur the lens, don't make pretty words do the duty once performed by ugly ones.

"Retard" is an offensive term, I think we can all agree. But in its own way, I find "differently abled" or even "special" to be far worse, because they minimize the struggle. They allow the rest of us to sigh and wipe away a tear while we watch some very touching report on the Today Show, and then say "Wow, thank you Meredith, for showing me the story of that brave little trouper!" And then we go on with our lives, knowing that someone is watching out for that precious little angel. Someone like Jesus, perhaps, or one of his dedicated soldiers on earth.

Or someone like me. Or you. Or no one at all, no one except the person who lives their life confined to a wheelchair or suffering from a debilitating condition that makes a nightmare out of the things that you and I take for granted, the everyday tasks and activities that give us our humanity, and can rob us of it when they are taken away.

I helped Schuyler take a preliminary eye test today, in anticipation of an hour-long appointment later this week for the glasses that she'll apparently be getting soon. I held her device for her while she identified the letters on the wall that she could read. She did a great job, and I was incredibly proud of her. She's making her way in the world, and she'll continue to do so with determination and enthusiasm and even optimism, but she'll also do it with a big dose of "fuck you" when needed. And she's not going to get that from People First Language. Kind words aren't going to open any doors for her, not a one. They might simply make her feel like a failure for being unable to open them herself.

Ultimately, People First Language feels to me like it exists not so much to help broken children like Schuyler, most of whom I suspect are tougher and more pragmatic than the people who love them perhaps realize. I think it works mostly for the people around them, those of us who aren't afflicted and yet lead lives forever changed by disability.

People First Language probably makes that life a little easier for the rest of us to bear, but honestly, I'm not sure it should be easier for us. In that respect, I'm not convinced that People First Language is putting the right people first.

I've seen it presented as a sort of universal truth, as if the rightness of People First Language is a given, with little room for argument. People First Language must be used, I read time and time again, like a moral imperative. The heartfelt and dedicated advocates of People First Language want very much for it to be accepted as a standard practice. Indeed, they often insist on it. But it's not universally accepted, although people who find it troubling are often nervous about discussing why. I'm a little nervous about writing this, to tell the truth, and we all know what an ass I can be.

The idea behind People First Language is simple, and inherent in the name of the concept. It puts the person first, allowing their basic existence to define them before their disability. People First Language describes what the person has, but not who that person is. By these rules, I am not a diabetic. I am a guy who has diabetes. The thinking behind People First Language says that identifying a person by their diagnosis can generate fear and pity, and works against the goal of inclusion. People First Language grants a person dignity, the thinking goes, by blunting the impact of their diagnosis on that person's self-image, and also in how they are perceived by the world.

"It's not 'political correctness,'" writes People First Language advocate Kathie Snow, "but good manners and respect."

Perhaps. I do see the point, and insofar as I think these kinds of perceptions are important issues, I can see some of the benefits of People First Language. I don't want Schuyler to be hurt by the world around her, and I certainly don't want her disability to make her feel like there's something wrong with her.

But here's the thing. As hard as it may be to admit this, there is something wrong with her. And admitting that she's broken on some level is difficult, and it feels harsh. But it's a harshness that comes from somewhere else, from whatever power you think hands out that kind of Very Special Gift. God if you believe in him, Fate if you don't, or just random shitty luck if that's how you roll. And the thing that it's easy to miss, because the idea breaks my heart too, is that no one is more aware of Schuyler's disability than Schuyler herself. When you think about it, that seems obvious, but for those of us who love her and care about her, it might be much easier to accept if we could adopt language that takes some of the sting out of her reality.

People First Language attempts to soften the language that we use to describe disability, and I understand why that's tempting. But in doing so, it doesn't blunt the monsters, not even a little. If you say, as People First Language instructs, that a paraplegic is NOT confined to a wheelchair or is NOT wheelchair-bound, but instead refer to them as "an individual who uses a wheelchair", you have taken away that wheelchair's power over that person in perception only. It even implies choice, at least in my opinion. I use things, and I use parts of myself, with intent. I don't think I'd say I use my heart, or my kidneys, because I am not given a choice, but I do use my legs. I choose to use them, and I can choose not to.

That sounds like I'm being obvious and glib, but it bothers me, and for some very real reasons. Because when you take away responsibility from the monster, who are you going to give it to? When you say that a person uses a wheelchair, you are setting up ownership of that disability. The monster doesn't have you. You have the monster.

But do we really want to hand ownership of that disability to a child who is struggling to understand their place in the world? Does handing responsibility for a disability over to the child give them an unreasonable sense of their own role in the possession of that disability? If you're using a wheelchair, then why not just stop? If that sounds silly to you, ask a now-grown child of divorced parents if they still, even if only in their secret hearts, take some measure of responsibility for their parents' breakup. Ask an adult with a disability if they ever wondered as kids what they did to deserve their situation. Ask them if they ever wonder that now.

If Schuyler isn't "non-verbal" but instead "communicates with an assistive technology device", then why? Why would she do that? If Schuyler doesn't feel like she is in the clutches of a monster to whom she brings the fight every day, that's great and my biggest dream made real. But if she then comes to the conclusion that she owns that lack of speech, then what can be the reason for its persistence? Is she not trying hard enough? Why isn't she fixing the issue herself? If she's not broken, then what's the problem? Lack of motivation? Is she simply not good enough? Not strong enough, or smart enough, or brave enough?

Schuyler as the victim (another word forbidden by People First Language) of Fate and its monster minion, as sad as that may sound, is infinitely preferable to Schuyler as the product of her own subtly-implied failure. I simply won't have it, any more than I'll have the idea of "acceptance" stand in the way of her hard work, and of ours. To my thinking, People First Language sets up an unreasonable expectation, taking the responsibility away from unfair forces at work in the world and instead laying it squarely at the feet of the very last people in the world who deserve to wonder if they somehow had this coming.

And don't even get me started on the ridiculous and unwieldy term "nondisabled" to describe neurotypical or "normal" people. That should offend anyone who loves the English language.

Listen. I get why people use People First Language. I understand the push to bring sensitivity to an often cold world. That's something I fight for as much as anyone else, after all. I wrote an entire goddamn book about it. But please try to understand, people. Don't just try to make it feel better. Don't blur the lens, don't make pretty words do the duty once performed by ugly ones.

"Retard" is an offensive term, I think we can all agree. But in its own way, I find "differently abled" or even "special" to be far worse, because they minimize the struggle. They allow the rest of us to sigh and wipe away a tear while we watch some very touching report on the Today Show, and then say "Wow, thank you Meredith, for showing me the story of that brave little trouper!" And then we go on with our lives, knowing that someone is watching out for that precious little angel. Someone like Jesus, perhaps, or one of his dedicated soldiers on earth.

Or someone like me. Or you. Or no one at all, no one except the person who lives their life confined to a wheelchair or suffering from a debilitating condition that makes a nightmare out of the things that you and I take for granted, the everyday tasks and activities that give us our humanity, and can rob us of it when they are taken away.

I helped Schuyler take a preliminary eye test today, in anticipation of an hour-long appointment later this week for the glasses that she'll apparently be getting soon. I held her device for her while she identified the letters on the wall that she could read. She did a great job, and I was incredibly proud of her. She's making her way in the world, and she'll continue to do so with determination and enthusiasm and even optimism, but she'll also do it with a big dose of "fuck you" when needed. And she's not going to get that from People First Language. Kind words aren't going to open any doors for her, not a one. They might simply make her feel like a failure for being unable to open them herself.

Ultimately, People First Language feels to me like it exists not so much to help broken children like Schuyler, most of whom I suspect are tougher and more pragmatic than the people who love them perhaps realize. I think it works mostly for the people around them, those of us who aren't afflicted and yet lead lives forever changed by disability.

People First Language probably makes that life a little easier for the rest of us to bear, but honestly, I'm not sure it should be easier for us. In that respect, I'm not convinced that People First Language is putting the right people first.

August 9, 2008

Speechificationalismness

Okay, I put my keynote address to the Assistive Technology Cluster Conference online.

Please keep in mind that it was delivered to a gathering of special education teachers, speech pathologists, occupational and physical therapists, school administrators and some parents of kids using assistive technology. It was also written with the (probably safe) assumption that most of them had never read the book or this blog, so there's material that may obviously seem familiar to you.

Oh, and also, I had a time slot of over an hour, so if it seems long to you as a reader, imagine how I felt. That's a lot of jabbering for one old man.

Please keep in mind that it was delivered to a gathering of special education teachers, speech pathologists, occupational and physical therapists, school administrators and some parents of kids using assistive technology. It was also written with the (probably safe) assumption that most of them had never read the book or this blog, so there's material that may obviously seem familiar to you.

Oh, and also, I had a time slot of over an hour, so if it seems long to you as a reader, imagine how I felt. That's a lot of jabbering for one old man.

August 8, 2008

Monster Slayers' Ball

Do you want to know a moment when this whole fancy pants book thing felt a little extra real recently? When I made a joke and about five hundred people laughed.

I gave the keynote address at the 2008 Assistive Technology Cluster Conference in Richardson, Texas last week. This is something that has been in the works for a while, and I was excited about it, in a "they want me to speak for how long?" sort of way. Excited, with a "good thing a wore my brown pants" element of terror mixed in.

I don't want to sound like I am tooting my own horn here, but honestly, I think it went really well. They laughed at my jokes (Looking for an easy laugh when talking to special educators? Make fun of No Child Left Behind...), almost no one left while I was talking, no one booed or threw anything at me, and when it was over, some of the people who came up to talk to me had been crying. There's nothing like seeing someone's runny mascara to make you feel like you got it right as a writer. I was more concerned about my delivery than the actual text, but I got through it without stammering too much or dropping any random F-bombs, so all in all, I'm pleased with how it went. Perhaps I'll put it online.

(Edited to add: Done.)

As is usual with this book and the appearances we've made, however, the real star was Schuyler. I put together a PowerPoint presentation (actually, on Apple's very cool Keynote software; imagine Powerpoint's hotter, sluttier sister) that was heavy on the Schuyler images, and that was a wise, if not particularly unexpected, move on my part. When I mentioned Schuyler's ability to communicate her defiance without words, the image on the three big screens got what was probably the best reaction of the whole speech. As hard as I work to represent her in my writing and in my advocacy, Schuyler speaks for herself best of all.

When my speech was over, the organizer of the conference invited Schuyler to come up to the front. In this huge room full of adults, Schuyler looked tiny and fragile to me, but she strode to the front without hesitation in her little black dress and newly-reddened hair, took the microphone and said, with confidence and almost comprehensibly, "Hi everyone!"

And THAT, my friends, was the best part of my keynote address.

The conference itself was fantastic, and very eye-opening for us. They gave us a table in the too-small exhibitors' hall, where we signed books and met teachers and parents and, most importantly, other people who were using assistive technology like Schuyler's Big Box of Words. These were young people with disabilities much more severe than Schuyler's, to the point that they had to struggle many times just to put their words in order. And yet, I don't think I can adequately describe how powerfully affecting it was to watch them navigate on their devices and communicate in full sentences, with complexity and nuance and humor. It gave me, and Schuyler most of all, a lot to consider where her own device usage is concerned.

One of the most fascinating parts of the conference for us was seeing exactly how much work is being done by some very smart people to advance the technology that kids like Schuyler are using. Prentke Romich, makers of the Big Box of Words, were well-represented, as usual. I'm always amazed at the people who work for that company, not just by how smart and committed they are to their work, but also just by the humor and confidence they exude. Two of their reps were device users themselves, and they were kind enough to come talk to Schuyler from time to time on their devices. You can probably imagine how weepy I became, on more than one occasion.

There were other companies represented, and a lot of very innovative technology on display. I came away with a lot of ideas and thoughts, some of which I'm going to share with PRC soon. The whole thing made me think about this in whole new ways.

But most of all, the thing I took away from this conference was an appreciation for the work that all these people are doing. Teachers, therapists, administrators, parents, advocates, all of them. When I looked out at that audience, the thing I felt most of all was humbled (and how often does THAT happen?). I was standing in front of the people who have made it their life's work to help kids like Schuyler.

Early in my speech, I said:

I've learned so much over the past few years, most of it about myself and my own capabilities, and all of it from Schuyler. Being there in front of those amazing people and being able to share my perspective with them was one of the singular honors of my life. And that's the truth.

I gave the keynote address at the 2008 Assistive Technology Cluster Conference in Richardson, Texas last week. This is something that has been in the works for a while, and I was excited about it, in a "they want me to speak for how long?" sort of way. Excited, with a "good thing a wore my brown pants" element of terror mixed in.

I don't want to sound like I am tooting my own horn here, but honestly, I think it went really well. They laughed at my jokes (Looking for an easy laugh when talking to special educators? Make fun of No Child Left Behind...), almost no one left while I was talking, no one booed or threw anything at me, and when it was over, some of the people who came up to talk to me had been crying. There's nothing like seeing someone's runny mascara to make you feel like you got it right as a writer. I was more concerned about my delivery than the actual text, but I got through it without stammering too much or dropping any random F-bombs, so all in all, I'm pleased with how it went. Perhaps I'll put it online.

(Edited to add: Done.)

As is usual with this book and the appearances we've made, however, the real star was Schuyler. I put together a PowerPoint presentation (actually, on Apple's very cool Keynote software; imagine Powerpoint's hotter, sluttier sister) that was heavy on the Schuyler images, and that was a wise, if not particularly unexpected, move on my part. When I mentioned Schuyler's ability to communicate her defiance without words, the image on the three big screens got what was probably the best reaction of the whole speech. As hard as I work to represent her in my writing and in my advocacy, Schuyler speaks for herself best of all.

When my speech was over, the organizer of the conference invited Schuyler to come up to the front. In this huge room full of adults, Schuyler looked tiny and fragile to me, but she strode to the front without hesitation in her little black dress and newly-reddened hair, took the microphone and said, with confidence and almost comprehensibly, "Hi everyone!"

And THAT, my friends, was the best part of my keynote address.

The conference itself was fantastic, and very eye-opening for us. They gave us a table in the too-small exhibitors' hall, where we signed books and met teachers and parents and, most importantly, other people who were using assistive technology like Schuyler's Big Box of Words. These were young people with disabilities much more severe than Schuyler's, to the point that they had to struggle many times just to put their words in order. And yet, I don't think I can adequately describe how powerfully affecting it was to watch them navigate on their devices and communicate in full sentences, with complexity and nuance and humor. It gave me, and Schuyler most of all, a lot to consider where her own device usage is concerned.

One of the most fascinating parts of the conference for us was seeing exactly how much work is being done by some very smart people to advance the technology that kids like Schuyler are using. Prentke Romich, makers of the Big Box of Words, were well-represented, as usual. I'm always amazed at the people who work for that company, not just by how smart and committed they are to their work, but also just by the humor and confidence they exude. Two of their reps were device users themselves, and they were kind enough to come talk to Schuyler from time to time on their devices. You can probably imagine how weepy I became, on more than one occasion.

There were other companies represented, and a lot of very innovative technology on display. I came away with a lot of ideas and thoughts, some of which I'm going to share with PRC soon. The whole thing made me think about this in whole new ways.

But most of all, the thing I took away from this conference was an appreciation for the work that all these people are doing. Teachers, therapists, administrators, parents, advocates, all of them. When I looked out at that audience, the thing I felt most of all was humbled (and how often does THAT happen?). I was standing in front of the people who have made it their life's work to help kids like Schuyler.

Early in my speech, I said:

It might be the most striking difference between our experience with the world of broken children and yours. As special educators and experts in assistive technology, you have sought out the monsters. You’ve armed yourselves with the knowledge and the tools to fight them, and you’ve gone into battle with your armor in place. For parents, the monsters have found us, in most cases sitting by the campfire in ignorant bliss, totally unprepared.

There’s a transition that special needs parents go through, and it’s one that I suspect never completes itself entirely. We go from seeing sad stories about kids with disabilities on television and saying "I can’t even begin to imagine how those parents deal with that" to becoming the parents who face it with our kids and for our kids. We learn quickly to conceal our fear, which is very great, and our self-doubts, which are many. We take hold of whatever we need in order to find that extra strength, whether it’s God or friends and family or a good stiff drink, and we draw our rubber swords. When we get to the battlefield, we find… you. You’re already there, our generals and our scouts, and you know the lay of the land. We’re not ready when we get there, not quite, but we will be soon enough. Once we get past our denial and our mourning for the child we always thought we’d have, we devote ourselves to the complicated, broken but equally wonderful child in its place. No one in the world is a quicker study than the special needs parent.

I've learned so much over the past few years, most of it about myself and my own capabilities, and all of it from Schuyler. Being there in front of those amazing people and being able to share my perspective with them was one of the singular honors of my life. And that's the truth.

August 6, 2008

The girl in the window

The Girl in the Window (St. Petersberg Times)

I don't have much to say about this, really. I'm not sure what there is to say. But I thought this was important, and if you trust my judgment and if you have ever been touched by Schuyler and the strange, internal world that she sometimes occupies but now has the tools to leave when she wants, then please go read this story, of a little girl who lives in that world permanently, and the horrible reason she got there in the first place.

(via Dooce)

-----

UPDATE, 8/13 - They've posted a follow-up article.

I don't have much to say about this, really. I'm not sure what there is to say. But I thought this was important, and if you trust my judgment and if you have ever been touched by Schuyler and the strange, internal world that she sometimes occupies but now has the tools to leave when she wants, then please go read this story, of a little girl who lives in that world permanently, and the horrible reason she got there in the first place.

(via Dooce)

-----

UPDATE, 8/13 - They've posted a follow-up article.

August 3, 2008

Passing of a Perpetual Exile

(1918-2008)

I've always had a deep love of Russian culture and history, and I have always counted three great contemporary Russians among my own personal heroes. Dmitri Shostakovich died in 1975, and Mstislav Rostropovich died last year. News from Russia tonight; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn has died at the age of 89.

I won't go into the particulars of Solzhenitsyn's legacy. The New York Times obituary I linked yo above is a pretty exhaustive one, and if you're not familiar with Solzhenitsyn, I hope you'll take some time to read it. Neither A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich nor especially The Gulag Archipelago are easy summer reads; indeed, I can't imagine very many people outside of Russia have read Gulag in its entirety. But you don't have to read much; like Holocaust history, the story of Stalinism (which hardly died with Stalin, or is dead even now) and the Russian terror state is probably too big for one person to encapsulate it. But Solzhenitsyn must have come close.

For me, there are two great chroniclers of the cruelty of life in the Soviet Union. Shostakovich showed us how it felt, and Solzhenitsyn told us how it was. The world is infinitely the poorer for his passing.

July 30, 2008

That one percent feels like a universal truth

When I've got some time, I'm going to write about the conference at which I spoke yesterday, which was an amazing and eye-opening experience, for Julie and me both but particularly for Schuyler.

Until then, however, I wanted to share something exceptional that I read this morning, a post on Jennifer Groneberg's blog. It seemed especially appropriate, given recent sobering events in the special needs community.

Among other things, it addresses fear, and does so in an unblinking way that really resonated with me. I am always happy to have the discussion about gentle terminology and inclusive language (which has come up again, not surprisingly), but this is a good example of exactly why I prefer direct language. Sometimes the monster is just plain scary, and calling it something besides a monster just doesn't do the job.

Thanks, Jennifer, for posting this.

Until then, however, I wanted to share something exceptional that I read this morning, a post on Jennifer Groneberg's blog. It seemed especially appropriate, given recent sobering events in the special needs community.

Among other things, it addresses fear, and does so in an unblinking way that really resonated with me. I am always happy to have the discussion about gentle terminology and inclusive language (which has come up again, not surprisingly), but this is a good example of exactly why I prefer direct language. Sometimes the monster is just plain scary, and calling it something besides a monster just doesn't do the job.

Thanks, Jennifer, for posting this.

July 26, 2008

"Hard times give me your open arms..."

Sometimes sadness feels distant, like Third World suffering. And then there are the times when it hits close to home.

Noted writer and special needs advocate Vicki Forman unexpectedly lost her son Evan this week. The subsequent torrent of sorrow and shock that have been moving through the online community of special needs parents and advocates speaks to the immediacy of Vicki's writing and the positive effect that she and her son have had on others who are trying to make their way in a world of silent monsters.

It also speaks to the quiet fear that so many of us carry through our lives. After I left a heartfelt but probably inadequate message on Special Needs Mama expressing my condolences, Vicki was kind enough to write to me. In her message, she mentioned the thing that we both knew already, the thing that all parents of special needs children know but rarely speak of, even amongst ourselves. It exists behind the inspirational stories and the moments that allow everyone to believe that strong people who fight the good fight will always triumph in the end. She referred to it as "a vulnerability that is unmentionable," and in Evan's case, it became more than he could bear.

It lurks, the biggest monster of them all. It watches and it waits, and sometimes it takes advantage of that moment of vulnerability. What it leaves behind in the short term is chaos. It leaves fear and a cold truth for those of us who live our lives, even on the best of days, casting brief but troubled looks over our shoulders. And for parents like Vicki, it leaves a pain that I can't even begin to imagine, although of course I've imagined it plenty over the last five years.

The thing is, however, it doesn't end there. People who have known me for years can attest that I am not the same person I was before Schuyler came into my life. Most parents are changed by their kids, but I'll go out on a limb just a bit and say that the parents of broken children are changed even more profoundly than most. Evan was just about Schuyler's age, and the years that Vicki and her family had with him have undoubtedly left them all different people than when they began this trip together. In Vicki's case, her writing and her advocacy over the years have allowed Evan to change a lot of people as well. I hope that when the pain has dulled a little bit, she'll see just how much he left behind, and what a legacy she has allowed for him.

As cliched as it may sound, that's how kids like Evan never die. Small comfort today, but true nonetheless.

---

Contributions in memory of Evan Kamida may be made to:

The Pediatric Epilepsy Fund at UCLA

Division of Pediatric Neurology

Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

22-474 MDCC

10833 Le Conte Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1752

Noted writer and special needs advocate Vicki Forman unexpectedly lost her son Evan this week. The subsequent torrent of sorrow and shock that have been moving through the online community of special needs parents and advocates speaks to the immediacy of Vicki's writing and the positive effect that she and her son have had on others who are trying to make their way in a world of silent monsters.

It also speaks to the quiet fear that so many of us carry through our lives. After I left a heartfelt but probably inadequate message on Special Needs Mama expressing my condolences, Vicki was kind enough to write to me. In her message, she mentioned the thing that we both knew already, the thing that all parents of special needs children know but rarely speak of, even amongst ourselves. It exists behind the inspirational stories and the moments that allow everyone to believe that strong people who fight the good fight will always triumph in the end. She referred to it as "a vulnerability that is unmentionable," and in Evan's case, it became more than he could bear.

It lurks, the biggest monster of them all. It watches and it waits, and sometimes it takes advantage of that moment of vulnerability. What it leaves behind in the short term is chaos. It leaves fear and a cold truth for those of us who live our lives, even on the best of days, casting brief but troubled looks over our shoulders. And for parents like Vicki, it leaves a pain that I can't even begin to imagine, although of course I've imagined it plenty over the last five years.

The thing is, however, it doesn't end there. People who have known me for years can attest that I am not the same person I was before Schuyler came into my life. Most parents are changed by their kids, but I'll go out on a limb just a bit and say that the parents of broken children are changed even more profoundly than most. Evan was just about Schuyler's age, and the years that Vicki and her family had with him have undoubtedly left them all different people than when they began this trip together. In Vicki's case, her writing and her advocacy over the years have allowed Evan to change a lot of people as well. I hope that when the pain has dulled a little bit, she'll see just how much he left behind, and what a legacy she has allowed for him.

As cliched as it may sound, that's how kids like Evan never die. Small comfort today, but true nonetheless.

---

Contributions in memory of Evan Kamida may be made to:

The Pediatric Epilepsy Fund at UCLA

Division of Pediatric Neurology

Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

22-474 MDCC

10833 Le Conte Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1752

July 23, 2008

On Michael Savage and Other Monsters

Before I begin, let's look at what exactly was said last week by Michael Savage, talk radio host and celebrated caveman:

I had no intention of addressing the whole Michael Savage issue here or anywhere else, mostly because what he said was pretty clearly stupid, but also for the simple reason that autism isn't my issue. I occasionally have disagreements with parents of autistic children, and in most cases it boils down to the fact that Schuyler is not autistic. Her condition does not in any way manifest itself like autism, not even her lack of speech, and my beliefs in how she should be cared for, how I refer to her condition and my expectations for her future are completely different from theirs. I have the utmost respect for these parents, and I like to think that the fight I bring on Schuyler's behalf will benefit them just as much. But still. Not my fight, not directly, anyway.

But then I followed a link that was showing up in my stats, and I found a discussion of Savage's remarks on a parenting forum. I found the link back to my blog, and to my irritation, it was in a post by someone who, while disdaining the manner in which Savage expressed his opinion, nevertheless defended his point about how kids are supposedly being over-diagnosed with autism by pointing out that Schuyler was originally misdiagnosed as being on the autism spectrum. You may be reading this blog for the first time right now, as a result of following that link.

So let me say a few things briefly and clearly. First of all, yes, it is true that Schuyler was misdiagnosed, by the Child Study Center at the Yale Medical School, with Pervasive Developmental Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS, or as I liked to call it, for its vague and unhelpful description, "PDD-WTF"), an autism spectrum disorder.

But I also think it's important to note that Schuyler's actual condition, Bilateral Perisylvian Polymicrogyria, is extremely rare, with perhaps as few as a thousand identified cases worldwide, and without the MRI that Schuyler eventually received, there was no way to identify what her monster really was. It was unlikely, even at Yale, that anyone was going to immediately get it right, particularly without a brain scan. Furthermore, we pushed for more tests when that diagnosis felt unsatisfactory, and those tests were granted without any resistance because her doctors agreed with us. Her misdiagnosis only stood for a few months, and was suspect from the beginning.

In other words, I don't think Schuyler's misdiagnosis is very helpful anecdotally. Are children being diagnosed prematurely with autism spectrum conditions? I have no idea; my kid isn't autistic, and even when she received that diagnosis, I don't think anyone ever seriously thought she was. I can't speak to how autism is being identified by doctors.

I do think, however, that it is important to realize that yes, autism is a serious, legitimate medical condition and one that affects thousands of families in ways that I can't even begin to fathom. Furthermore, I can't imagine there are really non-deranged people out there who believe otherwise. If there are people out there ready to put forth an intelligent argument in defense of that position, Michael Savage is not one of them. He's a buffoon, and I'm pretty sure he knows it.

Having said that, I don't believe he should be silenced for expressing his opinion. Typically, free speech only truly requires our democracy's defense when it is denied to the assmonkeys of the world; logical or popular positions (and why are they so rarely one and the same?) can usually take care of themselves.

Still, it's nice to know that sometimes the marketplace responds appropriately.

SAVAGE: Now, you want me to tell you my opinion on autism, since I'm not talking about autism? A fraud, a racket. For a long while, we were hearing that every minority child had asthma. Why did they sudden -- why was there an asthma epidemic amongst minority children? Because I'll tell you why: The children got extra welfare if they were disabled, and they got extra help in school. It was a money racket. Everyone went in and was told [fake cough], "When the nurse looks at you, you go [fake cough], 'I don't know, the dust got me.' " See, everyone had asthma from the minority community. That was number one.

Now, the illness du jour is autism. You know what autism is? I'll tell you what autism is. In 99 percent of the cases, it's a brat who hasn't been told to cut the act out. That's what autism is.

What do you mean they scream and they're silent? They don't have a father around to tell them, "Don't act like a moron. You'll get nowhere in life. Stop acting like a putz. Straighten up. Act like a man. Don't sit there crying and screaming, idiot."

Autism -- everybody has an illness. If I behaved like a fool, my father called me a fool. And he said to me, "Don't behave like a fool." The worst thing he said -- "Don't behave like a fool. Don't be anybody's dummy. Don't sound like an idiot. Don't act like a girl. Don't cry." That's what I was raised with. That's what you should raise your children with. Stop with the sensitivity training. You're turning your son into a girl, and you're turning your nation into a nation of losers and beaten men. That's why we have the politicians we have.

I had no intention of addressing the whole Michael Savage issue here or anywhere else, mostly because what he said was pretty clearly stupid, but also for the simple reason that autism isn't my issue. I occasionally have disagreements with parents of autistic children, and in most cases it boils down to the fact that Schuyler is not autistic. Her condition does not in any way manifest itself like autism, not even her lack of speech, and my beliefs in how she should be cared for, how I refer to her condition and my expectations for her future are completely different from theirs. I have the utmost respect for these parents, and I like to think that the fight I bring on Schuyler's behalf will benefit them just as much. But still. Not my fight, not directly, anyway.

But then I followed a link that was showing up in my stats, and I found a discussion of Savage's remarks on a parenting forum. I found the link back to my blog, and to my irritation, it was in a post by someone who, while disdaining the manner in which Savage expressed his opinion, nevertheless defended his point about how kids are supposedly being over-diagnosed with autism by pointing out that Schuyler was originally misdiagnosed as being on the autism spectrum. You may be reading this blog for the first time right now, as a result of following that link.

So let me say a few things briefly and clearly. First of all, yes, it is true that Schuyler was misdiagnosed, by the Child Study Center at the Yale Medical School, with Pervasive Developmental Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS, or as I liked to call it, for its vague and unhelpful description, "PDD-WTF"), an autism spectrum disorder.

But I also think it's important to note that Schuyler's actual condition, Bilateral Perisylvian Polymicrogyria, is extremely rare, with perhaps as few as a thousand identified cases worldwide, and without the MRI that Schuyler eventually received, there was no way to identify what her monster really was. It was unlikely, even at Yale, that anyone was going to immediately get it right, particularly without a brain scan. Furthermore, we pushed for more tests when that diagnosis felt unsatisfactory, and those tests were granted without any resistance because her doctors agreed with us. Her misdiagnosis only stood for a few months, and was suspect from the beginning.

In other words, I don't think Schuyler's misdiagnosis is very helpful anecdotally. Are children being diagnosed prematurely with autism spectrum conditions? I have no idea; my kid isn't autistic, and even when she received that diagnosis, I don't think anyone ever seriously thought she was. I can't speak to how autism is being identified by doctors.

I do think, however, that it is important to realize that yes, autism is a serious, legitimate medical condition and one that affects thousands of families in ways that I can't even begin to fathom. Furthermore, I can't imagine there are really non-deranged people out there who believe otherwise. If there are people out there ready to put forth an intelligent argument in defense of that position, Michael Savage is not one of them. He's a buffoon, and I'm pretty sure he knows it.

Having said that, I don't believe he should be silenced for expressing his opinion. Typically, free speech only truly requires our democracy's defense when it is denied to the assmonkeys of the world; logical or popular positions (and why are they so rarely one and the same?) can usually take care of themselves.

Still, it's nice to know that sometimes the marketplace responds appropriately.

July 20, 2008

Big Box of Inappropriate

Has it really been almost two weeks? I apologize for the silence. I've been working on a lot of things and it's kept me busy. "What are you writing these days?" I get asked a lot. Well, I have not one, not two but three speeches to write this summer, including a keynote address for this conference on technology in special education in which I have an hour and a half allocated for whatever I plan to say. An hour and a half. I predict lots of Powerpoint and perhaps a puppet show.

Summer with Schuyler continues to be sort of hit and miss, to be honest, although it's still a vast improvement over previous summers when she was being watched by snotty know-it-all college student interns working for the school district. (I still remember the 19 year-old tool who, when told that Schuyler needed to be encouraged to use her device, disagreed and backed up his position with "I am a psychology major...")

As much as she must love hanging out in the office with her forty year-old father, she's missing her school friends and it's beginning to show. We keep trying to arrange play dates with some of her AAC classmates, but everyone's busy during the summer (what is this word "vacation" of which you speak?) so it's hard to put together. She's got her cousins and a few neurotypical kids that she sees now and then, but I think that as much fun as she has, it still serves as a reminder of her brokenness, and as an eight year-old, she's not as in love with being different as she might have been once.

We've been trying to learn a new word in sign language every day, and she's shown some excitement for that. I think part of her enthusiasm has come from the fact that I've been letting her choose the words, which has led to such useful words for everyday use as "robot" and "bat" (on the day The Dark Knight opened, and no, I didn't take her to see it). Now that she's beginning to enjoy learning new words, we may start trying to sneak some useful ones in from time to time. Not that "robot" isn't a solid daily vocabulary tool.

The Big Box of Words remains her primary form of communication, however, or at least our main focus. One way of firing up her enthusiasm for it has been to add things to it that she and I say when we're teasing each other, which is, well, pretty often. We already added a little rhyme from my childhood that I taught her a while back to say when people eyeball her in public, so her device will now say "Stare stare, booger bear. Take a picture, I don't care." (When she's old enough, perhaps she'll replace it with "What are you looking at, assmonkey?") At lunch yesterday (at a Mexican restaurant, naturally), she asked me to add "Beans, beans, the magical fruit. The more you eat, the more you toot." Clearly, I am a fine, fine influence on my child. Her teachers are going to be so proud.

Speaking of which, last week Schuyler wanted to use her device to call me a "monkey fart" (honestly, I don't know why Julie teaches her these horrible things), and lo and behold, the Big Box of Words did not have the word "fart" programmed into it. You can probably see where this is going.

Twenty minutes later, Schuyler had a new subdirectory on the BBoW listing words associated with, well, bodily functions. Say what you will about the beauty of language and creating an appropriate and enriching environment for a child, but come on. An eight year old who can't say "fart" or "burp" or "booger" is not a complete human.

And honestly, just assigning icons to her new words made it all worthwhile.

Did I mention that I'm the keynote speaker at a professional educators' conference? I did.

Summer with Schuyler continues to be sort of hit and miss, to be honest, although it's still a vast improvement over previous summers when she was being watched by snotty know-it-all college student interns working for the school district. (I still remember the 19 year-old tool who, when told that Schuyler needed to be encouraged to use her device, disagreed and backed up his position with "I am a psychology major...")

As much as she must love hanging out in the office with her forty year-old father, she's missing her school friends and it's beginning to show. We keep trying to arrange play dates with some of her AAC classmates, but everyone's busy during the summer (what is this word "vacation" of which you speak?) so it's hard to put together. She's got her cousins and a few neurotypical kids that she sees now and then, but I think that as much fun as she has, it still serves as a reminder of her brokenness, and as an eight year-old, she's not as in love with being different as she might have been once.

We've been trying to learn a new word in sign language every day, and she's shown some excitement for that. I think part of her enthusiasm has come from the fact that I've been letting her choose the words, which has led to such useful words for everyday use as "robot" and "bat" (on the day The Dark Knight opened, and no, I didn't take her to see it). Now that she's beginning to enjoy learning new words, we may start trying to sneak some useful ones in from time to time. Not that "robot" isn't a solid daily vocabulary tool.

The Big Box of Words remains her primary form of communication, however, or at least our main focus. One way of firing up her enthusiasm for it has been to add things to it that she and I say when we're teasing each other, which is, well, pretty often. We already added a little rhyme from my childhood that I taught her a while back to say when people eyeball her in public, so her device will now say "Stare stare, booger bear. Take a picture, I don't care." (When she's old enough, perhaps she'll replace it with "What are you looking at, assmonkey?") At lunch yesterday (at a Mexican restaurant, naturally), she asked me to add "Beans, beans, the magical fruit. The more you eat, the more you toot." Clearly, I am a fine, fine influence on my child. Her teachers are going to be so proud.

Speaking of which, last week Schuyler wanted to use her device to call me a "monkey fart" (honestly, I don't know why Julie teaches her these horrible things), and lo and behold, the Big Box of Words did not have the word "fart" programmed into it. You can probably see where this is going.

Twenty minutes later, Schuyler had a new subdirectory on the BBoW listing words associated with, well, bodily functions. Say what you will about the beauty of language and creating an appropriate and enriching environment for a child, but come on. An eight year old who can't say "fart" or "burp" or "booger" is not a complete human.

And honestly, just assigning icons to her new words made it all worthwhile.

Did I mention that I'm the keynote speaker at a professional educators' conference? I did.

July 8, 2008

No Blue Fairy

The Big Box of Words has been such a positive thing for Schuyler and her future that I think I usually fail to give a completely balanced picture of the ups and downs that accompany her experience with assistive technology.

Of late, she's had something of a rough time with the BBoW. There are times, especially during the school year, when Schuyler really seems to dig the device and the very unique place she has in the world because of it. Lately, though, I think it's just pissing her off.

Part of the issue is summer. No school, no peer group of device users, and no structured classroom environment. Just her smelly old parents and lots of activities that are not even remotely BBoW-friendly. She loves to swim, for example; she has never willingly left the pool without at least a grumble or a plea for five more minutes. She'd stay in her swim suit all summer if she could, her device hidden safely away on dry land. For the Fourth of July, we went camping with my brother's family, and I can count the times I saw her use the device on one finger. I know because I made her do it, and while it wasn't exactly under protest, she definitely did the bare minimum required.

We've decided to try to vary her techniques a little, stepping back up to the sign language plate again, for example, as a parallel technique alongside the device. Schuyler's condition limits her fine motor abilities in her hands and thus keeps her from being truly skilled at signing, but that never kept her from having real enthusiasm for it. She learned most of her signs from the early Signing Time videos, which I think I've discussed before, and now that they're on PBS, the DVR catches new episodes every now and then and we all sit down and learn them together. Her signing is limited by her own monster-stifled, clumsy fingers and by the limited number of people who can understand her. Nevertheless, signing still presents an elegant way to speak that the Big Box of Words simply can't match, at least at this point where she's still constructing sentences and thoughts at a necessarily slower, sometimes maddening pace. She understands the necessity of the device, but I think she sees the beauty of sign language in a way that I am only now appreciating myself.

Recently, Schuyler has begun to outwardly express her own awareness of her monster. She has this thing she does now to explain it, a whole story told in gestures and sign language. She gently touches her throat and shakes her head. She then touches her head with her finger (the sign for "think") and draws a line down to her mouth, signifying how the things she wants to say don't make the trip from her brain to her mouth. I like how she recognizes that her voice is broken, but her mind is working. It's important for her to know that her thoughts are there, and they are magnificent.

The thing about this little mimed explanation of Schuyler's condition, however, is that no one taught it to her. It's all hers. While some people worry about how to tell her what's wrong with her and how to explain it in gentle terms that won't bruise her delicate psyche ("Don't call her broken!"), Schuyler has figured out her own harsh reality by herself and expresses it without a hint of self-pity or trauma. Schuyler knows her monster better than any of us; it's presumptuous for anyone else, even me, to pretend we understand it, too, or to think that we can somehow tell her something about it that she doesn't already know on some visceral level.

Lately, Schuyler has balked a few times in public at using the Big Box of Words to answer other people's questions, and the sense that I get from her is that she may be starting to feel, if not embarrassed, at least self-conscious about it. Schuyler may delight in being a weird little girl, but only when it is on her terms. A speech output device still represents her very best (and possibly only) chance of being able to spontaneously communicate any kind of real expressive thought, but it remains an unnatural way for a little girl to speak. I suspect the day is coming, and soon, when her desire to be "normal" is going to cause some serious heartbreak for her.

There's one literary figure with whom I have always associated Schuyler, although to even say it aloud breaks my oft-broken old father's heart right in two.

In her own very unique way, Schuyler is Pinocchio.

Of late, she's had something of a rough time with the BBoW. There are times, especially during the school year, when Schuyler really seems to dig the device and the very unique place she has in the world because of it. Lately, though, I think it's just pissing her off.

Part of the issue is summer. No school, no peer group of device users, and no structured classroom environment. Just her smelly old parents and lots of activities that are not even remotely BBoW-friendly. She loves to swim, for example; she has never willingly left the pool without at least a grumble or a plea for five more minutes. She'd stay in her swim suit all summer if she could, her device hidden safely away on dry land. For the Fourth of July, we went camping with my brother's family, and I can count the times I saw her use the device on one finger. I know because I made her do it, and while it wasn't exactly under protest, she definitely did the bare minimum required.

We've decided to try to vary her techniques a little, stepping back up to the sign language plate again, for example, as a parallel technique alongside the device. Schuyler's condition limits her fine motor abilities in her hands and thus keeps her from being truly skilled at signing, but that never kept her from having real enthusiasm for it. She learned most of her signs from the early Signing Time videos, which I think I've discussed before, and now that they're on PBS, the DVR catches new episodes every now and then and we all sit down and learn them together. Her signing is limited by her own monster-stifled, clumsy fingers and by the limited number of people who can understand her. Nevertheless, signing still presents an elegant way to speak that the Big Box of Words simply can't match, at least at this point where she's still constructing sentences and thoughts at a necessarily slower, sometimes maddening pace. She understands the necessity of the device, but I think she sees the beauty of sign language in a way that I am only now appreciating myself.

Recently, Schuyler has begun to outwardly express her own awareness of her monster. She has this thing she does now to explain it, a whole story told in gestures and sign language. She gently touches her throat and shakes her head. She then touches her head with her finger (the sign for "think") and draws a line down to her mouth, signifying how the things she wants to say don't make the trip from her brain to her mouth. I like how she recognizes that her voice is broken, but her mind is working. It's important for her to know that her thoughts are there, and they are magnificent.

The thing about this little mimed explanation of Schuyler's condition, however, is that no one taught it to her. It's all hers. While some people worry about how to tell her what's wrong with her and how to explain it in gentle terms that won't bruise her delicate psyche ("Don't call her broken!"), Schuyler has figured out her own harsh reality by herself and expresses it without a hint of self-pity or trauma. Schuyler knows her monster better than any of us; it's presumptuous for anyone else, even me, to pretend we understand it, too, or to think that we can somehow tell her something about it that she doesn't already know on some visceral level.

Lately, Schuyler has balked a few times in public at using the Big Box of Words to answer other people's questions, and the sense that I get from her is that she may be starting to feel, if not embarrassed, at least self-conscious about it. Schuyler may delight in being a weird little girl, but only when it is on her terms. A speech output device still represents her very best (and possibly only) chance of being able to spontaneously communicate any kind of real expressive thought, but it remains an unnatural way for a little girl to speak. I suspect the day is coming, and soon, when her desire to be "normal" is going to cause some serious heartbreak for her.

There's one literary figure with whom I have always associated Schuyler, although to even say it aloud breaks my oft-broken old father's heart right in two.

In her own very unique way, Schuyler is Pinocchio.

July 1, 2008

"A Good Read"

(I swear to God, I thought I mentioned this already. I believe it was in the Father's Day post that got scrapped when I wrote about Tim Russert instead. My brain is apparently turning into pudding. Welcome to thirty-ten. Now get off my lawn.)

A few weeks ago, Naomi Shulman, research chief at Wondertime Magazine, wrote a very nice recommendation for Schuyler's Monster titled "A Good Read". I was of course happy to get a good review; it sure beats the alternative of a bad one or even worse, none at all.

I was especially touched to get yet another positive mention in Wondertime because they've been so supportive and great about my book. They featured a lengthy excerpt back in their March issue, which is nice online but looked absolutely breathtaking in its print layout. I was also interviewed by Naomi for a follow-up interview on the website. Wondertime has been a good friend to me and my family from the very beginning.

It's especially nice to have this coming from Naomi, who was an exceptionally pleasant and professional interviewer and who has been following Schuyler's story since before her diagnosis. I keep discovering over and over again how deeply Schuyler has touched so many people, and how the connections she's made through her story circle back around to us again and again.

So thank you, Naomi. This means the world to me, and that's the truth.

A few weeks ago, Naomi Shulman, research chief at Wondertime Magazine, wrote a very nice recommendation for Schuyler's Monster titled "A Good Read". I was of course happy to get a good review; it sure beats the alternative of a bad one or even worse, none at all.

I was especially touched to get yet another positive mention in Wondertime because they've been so supportive and great about my book. They featured a lengthy excerpt back in their March issue, which is nice online but looked absolutely breathtaking in its print layout. I was also interviewed by Naomi for a follow-up interview on the website. Wondertime has been a good friend to me and my family from the very beginning.

It's especially nice to have this coming from Naomi, who was an exceptionally pleasant and professional interviewer and who has been following Schuyler's story since before her diagnosis. I keep discovering over and over again how deeply Schuyler has touched so many people, and how the connections she's made through her story circle back around to us again and again.

So thank you, Naomi. This means the world to me, and that's the truth.

June 29, 2008

Vox monstrum

Sunday mornings are usually pretty relaxed around here. We don't go to church, the Baby Jesus keeps us from having Chick-fil-A and neither of us ever work on Sundays, so we usually get up late and have a lazy breakfast around the apartment. It's nice; even if we've got lots to do, it can all wait.

The three of us were sitting on the bed in our pjs, and Schuyler had her Big Box of Words with her so she could tell us about the beach in Connecticut. This naturally led to the topic of mermaids, as most conversations with Schuyler eventually do. When, in the midst of our discussion, we informed her that a boy mermaid was actually a merman, she asked me to add it to her device. Julie left us to our programming fun.

While we were adding words and making changes to the device, Schuyler and I ended up somehow on the voice settings, where the BBoW user can select the voice that she wants to represent her. There are maybe a dozen different voices, male and female, but there's only one (named "Kit") that sounds specifically like a child's voice.

Kit has been Schuyler's voice all along, and in a weird sort of way, it has become her recognizable voice to me. When we were being interviewed for public radio a few months ago, Schuyler thought it would be funny to reset the voice settings so that instead of little kid Kit's voice, the box suddenly sounded like some kind of menacing robot invader from Mars. She thought it was great fun, of course, and I found the experience surprisingly upsetting. Kit had become Schuyler's voice to me, and in some respects at least a part of who she really is on a fundamental level.

This morning, as I showed her the different voices and how they could be tweaked by changing the rate of speed, the pitch and the variance of pitch (ranging from robotic to Shatneresque), Schuyler grew very interested. She pointed to the device, and then to herself. Since we were in the settings mode, she had to speak with her hands.

She held her hands far apart ("big"), drew her thumb across her cheek ("girl") and then pointed to her throat ("voice").

Schuyler wanted a big girl voice.

We've been trying to push her to use the device this summer and have met with success, at least much of the time. We've always encouraged her her to take ownership of the BoW, adding words and changing pronunciations at her request. Now she was asking for a major change, and one that was very, very personal, both for her as a user and for the rest of us who interact with her every day.

We sat and spent a good half hour going through the different choices, and she finally chose "Ursula", which we then tweaked to bring the pitch up to a slightly more girlish sound and to add a bit of lilt to its patterns. What she ended up with was a voice completely customized to her wishes.

Broken children grow up like everyone else, although perhaps in ways and via paths we never anticipate. Schuyler has a big girl voice now. I only wish the rest of her big girl transformations were going to be that easy.

The three of us were sitting on the bed in our pjs, and Schuyler had her Big Box of Words with her so she could tell us about the beach in Connecticut. This naturally led to the topic of mermaids, as most conversations with Schuyler eventually do. When, in the midst of our discussion, we informed her that a boy mermaid was actually a merman, she asked me to add it to her device. Julie left us to our programming fun.

While we were adding words and making changes to the device, Schuyler and I ended up somehow on the voice settings, where the BBoW user can select the voice that she wants to represent her. There are maybe a dozen different voices, male and female, but there's only one (named "Kit") that sounds specifically like a child's voice.

Kit has been Schuyler's voice all along, and in a weird sort of way, it has become her recognizable voice to me. When we were being interviewed for public radio a few months ago, Schuyler thought it would be funny to reset the voice settings so that instead of little kid Kit's voice, the box suddenly sounded like some kind of menacing robot invader from Mars. She thought it was great fun, of course, and I found the experience surprisingly upsetting. Kit had become Schuyler's voice to me, and in some respects at least a part of who she really is on a fundamental level.

This morning, as I showed her the different voices and how they could be tweaked by changing the rate of speed, the pitch and the variance of pitch (ranging from robotic to Shatneresque), Schuyler grew very interested. She pointed to the device, and then to herself. Since we were in the settings mode, she had to speak with her hands.

She held her hands far apart ("big"), drew her thumb across her cheek ("girl") and then pointed to her throat ("voice").

Schuyler wanted a big girl voice.

We've been trying to push her to use the device this summer and have met with success, at least much of the time. We've always encouraged her her to take ownership of the BoW, adding words and changing pronunciations at her request. Now she was asking for a major change, and one that was very, very personal, both for her as a user and for the rest of us who interact with her every day.

We sat and spent a good half hour going through the different choices, and she finally chose "Ursula", which we then tweaked to bring the pitch up to a slightly more girlish sound and to add a bit of lilt to its patterns. What she ended up with was a voice completely customized to her wishes.

Broken children grow up like everyone else, although perhaps in ways and via paths we never anticipate. Schuyler has a big girl voice now. I only wish the rest of her big girl transformations were going to be that easy.

June 25, 2008

Summer monsters

It's been a while since I've really had much to say here. I haven't been staying away because of any great tragedy. I've just felt, I don't know. Quiet, I suppose.

The early days of summer have been different this year, for the simple reason that we've elected to keep Schuyler at home with us rather than handing her over to another summer program. I feel like I got adequate practice writing angry emails to administrators last summer, after all. The one thing her summer programs have had in common for some time has been the lack of progress she's made on her Big Box of Words. When she was at the YMCA, she never used it because they were constantly playing hard and swimming and having fun being feral kids on the go go go. Last summer, she didn't use it because the people taking care of her were too busy searching for a quarter for the clue bus.