Schuyler invited me into her room to hear a story she was going to tell some of her toy friends. I grabbed the Flip camera and just started shooting.

What you have here is basically about ten minutes of Schuyler being Schuyler, assembling her rogue's gallery of monsters and monkeys and making up stories about dinosaurs and sock monkeys. She didn't actually tell much of a story, aside from an exciting sock monkey fight sequence towards the end, but it's still a good example of what it is like to listen to Schuyler express herself without much in the way of prompting or direction.

I thought about trying to do subtitles, since Julie and I together can decipher most of it, but I don't know. Part of the reality of visiting Schuyler's world, both the charm and the frustration, is the work that you as the listener must do to understand and follow her.

So instead I give you the first line of her story. It makes sense, if you think like Schuyler, which I try to do every day, in my own way.

"One thousand years ago, dinosaurs were dead. They were SO white, like this dinosaur."

Schuyler is my weird and wonderful monster-slayer. Together we have many adventures.

April 26, 2011

April 24, 2011

April 20, 2011

Spring

I have a love/hate relationship with spring in Texas.

I love it for the storms that roll in during the late afternoons, setting off a flurry of emailed warnings and text messages and little tornado icons in the corner of every local television broadcast. Giant walls of clouds shamble in from the west, flashing lightning and setting off car alarms with great grumbles of thunder. The tornado sirens wail in the distance, cranking up a few seconds apart as they're triggered in town after town, running from Frisco and Allen to the north, down through Plano and Richardson, slightly out of sync so that they sound like a choir of tormented ghosts. After a while, the wailing stops, and for a brief moment I am disappointed that the danger is over.

But no, the siren has stopped so that the monstrous voice can intone, clearly and with divine authority, "Seek shelter immediately! Seek shelter immediately!" And suddenly I am thrilled again, feeling that tingle that suggests that the world might still be an exciting place, and it might carry danger and death, or it might just be full of lightning and thunder and waves of horizontal rain from time to time. I ignore the mathematics of tornados, because if I think about the incredibly remote chances of actually experiencing one, even in Texas, then I'll be aware that it really is just rain, and thunder and lightning, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

I love the storms, as only a renter can.

I kind of hate spring, too.

Spring is the season of IEP meetings, where we stretch Schuyler's monster out on a table and examine it, looking for signs of weakness that might be exploited, places where its hide might be pierced, even though every year we find that it is as inpenetrable as ever. Every spring, I find the enthusiasm and the "Why not?" of Schuyler's school has diminished just a little more, and the pragmatism and the downturned eyes and the "Here's why not..." has grown a little stronger in the passing year.

No one's talking about graduation anymore.

Spring is the season of the TAKS test, the Texas manifestation of No Child Left Alive, which for special needs kids invariably means "the test that you spend weeks preparing for even though you are probably going to fail it and no one believes you can pass it anyway, but Jesus Howard Christ, we are going to be ready for this motherfucker anyway, and sorry all your typical friends passed it but you didn't, but then again, you're DIFFERENT, and this is one more solid illustration of exactly how much that ISN'T a good thing, because you're not in Holland, you're in a place where you are measured against neurotypical kids, and it's not fair but it's the law, so let's take this shitty test, shall we?"

Schuyler did not pass the reading or math portions of the TAKS, we learned today. She didn't even come close.

I didn't tell her. I'm not sure if I ever will.

Well, I'm not so much worried about what comes next. Julie called the school principal (because we are Those Parents) a few minutes after I got the call from Schuyler's home room teacher telling me the bad TAKS news, in tones suggesting that the very best moment she could imagine in her future might be the one in which this phone call was over. The principal was supportive and reassuring, as she has always been.

I don't believe the school would try to hold Schuyler back from moving on to the next grade level, especially since I believe that their goals for her have shifted subtly from "she's going to graduate one day" to something more like "we're going to do the very best we can to teach her by exposing her as much information as we can, and maybe, just maybe, she'll absorb enough that her future will be, well, we don't know exactly, but maybe something good". They've become realists, in ways that we as Schuyler's Official Designated Overbelievers cannot.

I hate the test because it re-enforces something that Schuyler already knows. It tells her not to overbelieve. It tells her, and her teachers, and us, and I hope she refuses to listen but I wonder.

Spring is the season when we talk about all these things, and so in a very real sense, it's the season in which I despair.

This spring has been harder than most, with the added factor of possible seizures, the ones I've written about so much that I just don't want to anymore, and which will hopefully get THEIR spring portrait taken soon by Schuyler's neurologist. It's been hard for Schuyler because she's scared and frustrated and confused, she doesn't understand what is (maybe) happening to her body and her brain, which she thinks is mad at her. But her anxiety passes, and she finds joy in the world around her. She is anxiety-free ninety percent of the time, which I find comforting, even though last year it was probably ninety-five percent. I try not to project what next spring's percentage might be.

Of my own percentages, I dare not stop and take measure. Over the past six months or so, I have found that if I keep moving, if I just focus on Schuyler and try to toss the occasional bone to the dogs in my head so they don't bark so much, I'm okay. And that's enough for now.

One thing I love about spring is how it promises summer. Schuyler becomes impatient with school in a way that is extremely typical, I suspect. She begins asking about the pool, which inexplicably won't open for another few weeks, and when we walk through Target, she gravitates toward the swim suits, begging for a new one even though she simply cannot choose just one that she likes. Her skin already starts tanning, although this year she is left with strange little pale rings on her arms from the wristbands that she wears to discreetly address her drooling. She sees commercials on television for the newest roller coaster at Six Flags and says "Oh yeah!" before breathlessly begging to go, soon, tomorrow, now.

Schuyler's feelings about spring are pretty simple. She experiences spring and she thinks of the future. Unlike me, it doesn't scare the hell out of her. In that respect, I envy her, deeply.

April 12, 2011

Quiet Girl

April 10, 2011

Waiting for Polly

This is what we do now. We watch Schuyler, and we wait for signs that she's having absence seizures, or not having seizures, we wait to know if she's going to be okay, or in what ways she's not. This is who we are now, both of us. I'm not an author, I'm not a father or a husband or a friend or whatever else. I am a watcher. It feels like it's all I do now. And honestly, at least for the past few months, it really sort of is.

Tonight, I saw Schuyler have an absence seizure, I think. I don't know, because without an EEG being administered, and administered at the right moment, we can't know for sure. But tonight, as we shopped at Target, I looked down and noticed Schuyler staring in front of her, mostly motionless except for a very very slight movement of her mouth that I may very well have imagined. I only observed her staring for maybe five or ten seconds, but she could have been doing it for a little longer. After she came back from whatever place she was visiting, she was drooly and crabby and seemed confused for a few minutes. Then she shook it off. Shortly after that, she suddenly needed to go to the bathroom. She went again before we left the store.

Later, after we got home, she suddenly ran to the bathroom again, this time having a very small accident before she got there. Neither of us were watching her that time, but based on her behavior after, I suspect she probably had another absence seizure.

Schuyler is confused by the ways that her body is suddenly betraying her. She doesn't understand it. Just the early puberty stuff alone is blowing her mind, after all. Add to that the further loss of control that she seems to be having, and you end up with a little girl who is frustrated and frightened, and who, when pressed for information on what she perceives, lacks the descriptive language to explain.

"My head feels weird."

"It's my little monster."

"My brain is mad at me."

Well, I don't know. Perhaps she does a fine job of explaining, in her own way.

In a few weeks, Schuyler will visit her neurologist, and hopefully she'll get another EEG, perhaps another extended weekend one where they glue a bunch of wires to her head and wait, like a hunter watching a trap from a blind. That's the best we can hope for, that something will happen during this tight window of opportunity. An author friend who has experience with absence seizures brilliantly described it as "like trying to take a polaroid of a ghost". That's perfect.

And it may all be nothing. It's feeling less and less like nothing, but then, watching for this particular phantom is making us twitchy and paranoid. We find ourselves falling into the oldest cliche, repeated endlessly by countless parents of broken children.

"We just want an answer, even if it's bad."

We said that before, when we had no idea of the severity of Schuyler's monster, and ultimately we didn't end up feeling quite that relieved once we got that answer. If this new monster introduces itself one day with a full blown grand mal seizure, I guarantee we won't be grateful to KNOW then, either. But the uncertainty wears you down. The watching, and the waiting.

Do you know what I miss? I miss being a funny writer. There was a time, long before all this, long before I discovered what I would be writing about and worrying about for the remainder of my life, when I just wrote funny stuff. Jesus Howard Christ, I miss those days.

Tonight, I saw Schuyler have an absence seizure, I think. I don't know, because without an EEG being administered, and administered at the right moment, we can't know for sure. But tonight, as we shopped at Target, I looked down and noticed Schuyler staring in front of her, mostly motionless except for a very very slight movement of her mouth that I may very well have imagined. I only observed her staring for maybe five or ten seconds, but she could have been doing it for a little longer. After she came back from whatever place she was visiting, she was drooly and crabby and seemed confused for a few minutes. Then she shook it off. Shortly after that, she suddenly needed to go to the bathroom. She went again before we left the store.

Later, after we got home, she suddenly ran to the bathroom again, this time having a very small accident before she got there. Neither of us were watching her that time, but based on her behavior after, I suspect she probably had another absence seizure.

Schuyler is confused by the ways that her body is suddenly betraying her. She doesn't understand it. Just the early puberty stuff alone is blowing her mind, after all. Add to that the further loss of control that she seems to be having, and you end up with a little girl who is frustrated and frightened, and who, when pressed for information on what she perceives, lacks the descriptive language to explain.

"My head feels weird."

"It's my little monster."

"My brain is mad at me."

Well, I don't know. Perhaps she does a fine job of explaining, in her own way.

In a few weeks, Schuyler will visit her neurologist, and hopefully she'll get another EEG, perhaps another extended weekend one where they glue a bunch of wires to her head and wait, like a hunter watching a trap from a blind. That's the best we can hope for, that something will happen during this tight window of opportunity. An author friend who has experience with absence seizures brilliantly described it as "like trying to take a polaroid of a ghost". That's perfect.

And it may all be nothing. It's feeling less and less like nothing, but then, watching for this particular phantom is making us twitchy and paranoid. We find ourselves falling into the oldest cliche, repeated endlessly by countless parents of broken children.

"We just want an answer, even if it's bad."

We said that before, when we had no idea of the severity of Schuyler's monster, and ultimately we didn't end up feeling quite that relieved once we got that answer. If this new monster introduces itself one day with a full blown grand mal seizure, I guarantee we won't be grateful to KNOW then, either. But the uncertainty wears you down. The watching, and the waiting.

Do you know what I miss? I miss being a funny writer. There was a time, long before all this, long before I discovered what I would be writing about and worrying about for the remainder of my life, when I just wrote funny stuff. Jesus Howard Christ, I miss those days.

April 6, 2011

Pretend and not pretend

The past seven days have been... well, up and down.

Last week, the three of us flew to Nashville for the Second Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Workshop at the Kennedy Center at Vanderbilt University. Julie and I were fortunate enough to speak on a panel of some extraordinary parents, and once again the conference was transformative for us all. We left feeling enlightened, valued, and perhaps even daring to be hopeful.

The day after we returned, Schuyler had another accident at school. She had yet another one today.

"I felt weird," she told me today as I asked her about it.

"You felt weird?" I repeated back to her, which is how you communicate verbally with Schuyler.

"Yeah," she said. "I felt weird in my head." She paused for a moment, considering. Finally she said, "I think it was Polly. The little monster in my head."

I have no idea what's going on, or how much her issues are related to her polymicrogyria or absence seizures that may or may not be happening. Before the end of the month, she will have seen a doctor and a neurologist. Maybe we'll have some answers. Perhaps not. Probably we'll have different questions.

Schuyler admitted to me that she is a little scared by this. She said she was a little scared, but also that she is Drummer Girl, and Drummer Girl isn't afraid of anything, so I guess that's her new talisman. We drove around listening to loud drum music (mostly music from Bear McCreary's score to Battlestar Galactica, which contains some of the coolest and most fearless percussion music I've ever heard) and picked up Tron from the RedBox so Schuyler could watch the cool girl with her same haircut who kicks ass. We didn't talk about her accident or her fear any further. Because Drummer Girl isn't afraid of tiny monsters that make her wet her pants.

I find it interesting that she has latched on to this idea of Polly. Schuyler does pretty well with metaphors, maybe because so much of what she experiences in her world is hard to explain. It's a little less confusing when she can believe in the invisible and the imaginary, even though she will also tell you that fairies and monsters are pretend. ("Dinosaurs were real, but they are pretend now," she informed me the other day.) She is comforted by them even as she knows they aren't real. Schuyler doesn't need Jesus. She's got Tinkerbell, and King Kong, and she's got Polly, who is the enemy but also her constant companion.

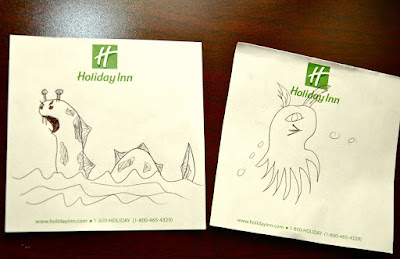

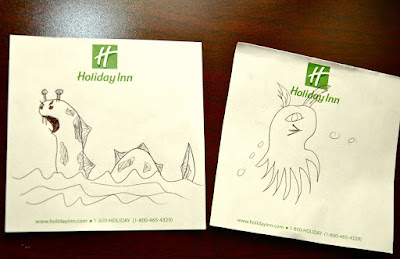

While we were in Nashville, Schuyler asked Julie and I to draw monsters for us. Julie drew something like an octopus with a chicken beak and antennas that shoot lightning, while I opted for the old school grumpy sea monster. Schuyler liked them both and displayed them prominently in the hotel room the whole weekend.

She liked them for what they were, but of course, they weren't her monsters. Hers is invisible, pretend and yet not pretend, and ultimately unknowable. We know it by its footprints, by the chaos it leaves behind.

Last week, the three of us flew to Nashville for the Second Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Workshop at the Kennedy Center at Vanderbilt University. Julie and I were fortunate enough to speak on a panel of some extraordinary parents, and once again the conference was transformative for us all. We left feeling enlightened, valued, and perhaps even daring to be hopeful.

The day after we returned, Schuyler had another accident at school. She had yet another one today.

"I felt weird," she told me today as I asked her about it.

"You felt weird?" I repeated back to her, which is how you communicate verbally with Schuyler.

"Yeah," she said. "I felt weird in my head." She paused for a moment, considering. Finally she said, "I think it was Polly. The little monster in my head."

I have no idea what's going on, or how much her issues are related to her polymicrogyria or absence seizures that may or may not be happening. Before the end of the month, she will have seen a doctor and a neurologist. Maybe we'll have some answers. Perhaps not. Probably we'll have different questions.

Schuyler admitted to me that she is a little scared by this. She said she was a little scared, but also that she is Drummer Girl, and Drummer Girl isn't afraid of anything, so I guess that's her new talisman. We drove around listening to loud drum music (mostly music from Bear McCreary's score to Battlestar Galactica, which contains some of the coolest and most fearless percussion music I've ever heard) and picked up Tron from the RedBox so Schuyler could watch the cool girl with her same haircut who kicks ass. We didn't talk about her accident or her fear any further. Because Drummer Girl isn't afraid of tiny monsters that make her wet her pants.

I find it interesting that she has latched on to this idea of Polly. Schuyler does pretty well with metaphors, maybe because so much of what she experiences in her world is hard to explain. It's a little less confusing when she can believe in the invisible and the imaginary, even though she will also tell you that fairies and monsters are pretend. ("Dinosaurs were real, but they are pretend now," she informed me the other day.) She is comforted by them even as she knows they aren't real. Schuyler doesn't need Jesus. She's got Tinkerbell, and King Kong, and she's got Polly, who is the enemy but also her constant companion.

While we were in Nashville, Schuyler asked Julie and I to draw monsters for us. Julie drew something like an octopus with a chicken beak and antennas that shoot lightning, while I opted for the old school grumpy sea monster. Schuyler liked them both and displayed them prominently in the hotel room the whole weekend.

She liked them for what they were, but of course, they weren't her monsters. Hers is invisible, pretend and yet not pretend, and ultimately unknowable. We know it by its footprints, by the chaos it leaves behind.

April 4, 2011

The Season for Overbelieving

Today, Schuyler began taking the TAKS test. (This is the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills, our version of the No Child Left Behind nonsense.)

I've talked about this before.

If you want to know my feelings about kids with disabilities and standardized testing, follow that link and read what I wrote two years ago. I don't think my outlook has changed on this at all; indeed, they didn't change even after Schuyler passed part of the test.

It's a cliche, perhaps, but this week, I feel like my child is being left behind. At least she won't have a lot of homework. More time for self-esteem repair, I suppose. Since everyone involved in education is bitching about NCLB this time of year, I'll leave it at that.

I've sort of come to dread the spring as far as Schuyler's school experience is concerned. It's a one-two punch of TAKS testing (and all its accompanying anxiety) and the following meeting to discuss Schuyler's IEP for the following year. Last year, the school district's educational diagnostician asked for (and was denied) our permission to administer a new cognition measurement test (basically, an IQ test) to Schuyler. She even admitted, without hesitation, that she believed such a test would reveal Schuyler to fall within the range associated with mental retardation (or whatever she calls it now, post-Rosa's Law).

That wasn't a good IEP.

I wrote about this last year, in a post titled "Truth can be a monster, too", and looking back on it now, I think it was probably one of the more important things I've written publicly about Schuyler's academic situation. It certainly paints a more accurate picture than what I wrote in my book as I tried to look into her future.

At that time, I was talking about Schuyler being mainstreamed at an age-appropriate level and one day joining her typical classmates and graduating from high school with them. But all of that was a lie, albeit an unintentional one. Schuyler's inclusion was something of a Potemkin village, and we happily allowed ourselves to buy into the fiction for far too long. We believed what we wanted to believe, to our utter shame.

"Truth can be a monster, too" ended like this, with some of the hardest words I think I ever had to write, hardest of all because they might have been loaded with frustration and sadness, but they were fat with truth, too:

A year later, I'm not sure how much has changed. I never made peace with the idea that Schuyler might be MR, and in fact I believe more than ever that she is not. Am I overbelieving in her, as I also expressed last spring? Perhaps, but I still think that as her father and one of her two chief advocates, overbelieving in Schuyler is exactly appropriate. Furthermore, and this is where there is perhaps the potential for disagreement amongst the members of the IEP team, I believe that overbelieving is right and appropriate for every single teacher and therapist who works with her. Every single one of them. Period.

I've already met with someone who will, I hope, be key to some success for Schuyler. A couple of weeks ago, I picked her up from school and took her to meet the band director at her new middle school, and after evaluating Schuyler's abilities on a few different possible choices, it was decided that percussion will be the best choice. Schuyler the drummer girl. Just imagine it.

I've talked about this before.

If you want to know my feelings about kids with disabilities and standardized testing, follow that link and read what I wrote two years ago. I don't think my outlook has changed on this at all; indeed, they didn't change even after Schuyler passed part of the test.

It's a cliche, perhaps, but this week, I feel like my child is being left behind. At least she won't have a lot of homework. More time for self-esteem repair, I suppose. Since everyone involved in education is bitching about NCLB this time of year, I'll leave it at that.

I've sort of come to dread the spring as far as Schuyler's school experience is concerned. It's a one-two punch of TAKS testing (and all its accompanying anxiety) and the following meeting to discuss Schuyler's IEP for the following year. Last year, the school district's educational diagnostician asked for (and was denied) our permission to administer a new cognition measurement test (basically, an IQ test) to Schuyler. She even admitted, without hesitation, that she believed such a test would reveal Schuyler to fall within the range associated with mental retardation (or whatever she calls it now, post-Rosa's Law).

That wasn't a good IEP.

I wrote about this last year, in a post titled "Truth can be a monster, too", and looking back on it now, I think it was probably one of the more important things I've written publicly about Schuyler's academic situation. It certainly paints a more accurate picture than what I wrote in my book as I tried to look into her future.

At that time, I was talking about Schuyler being mainstreamed at an age-appropriate level and one day joining her typical classmates and graduating from high school with them. But all of that was a lie, albeit an unintentional one. Schuyler's inclusion was something of a Potemkin village, and we happily allowed ourselves to buy into the fiction for far too long. We believed what we wanted to believe, to our utter shame.

"Truth can be a monster, too" ended like this, with some of the hardest words I think I ever had to write, hardest of all because they might have been loaded with frustration and sadness, but they were fat with truth, too:

For all my fancy book events and all my inspirational speeches and all my "gee, what a dad!" accolades, in the end I might be just like any other parent of a disabled child who has convinced themselves that the future is going to be easier, not harder, than the past and the present. I've looked at families with kids who sit solidly within that MR diagnosis and I've counted myself fortunate that my daughter has future options unavailable to them, but that might not really be true after all. It's entirely possible that I've stupidly and arrogantly pitied my own people.

My love for Schuyler has made me a believer and an unwavering advocate, but it might also be making me into a fool. And that's hard to face.

So how do I feel? I'm tired. It's exhausting, trying to build a fantasy world in which you child's disability isn't going to hold her back forever. It's a full-time job, convincing myself that everything's going to work out somehow and that one day she'll tell people "Why, there was a time when my teachers thought I was retarded, and look at me now! My parents believed in me, and they were right. I'd like to dedicate this Pulitzer to them."

And it requires a constant, unblinking effort to convince myself of the very very pretty lie that my little girl is going to be okay.

A year later, I'm not sure how much has changed. I never made peace with the idea that Schuyler might be MR, and in fact I believe more than ever that she is not. Am I overbelieving in her, as I also expressed last spring? Perhaps, but I still think that as her father and one of her two chief advocates, overbelieving in Schuyler is exactly appropriate. Furthermore, and this is where there is perhaps the potential for disagreement amongst the members of the IEP team, I believe that overbelieving is right and appropriate for every single teacher and therapist who works with her. Every single one of them. Period.

I've already met with someone who will, I hope, be key to some success for Schuyler. A couple of weeks ago, I picked her up from school and took her to meet the band director at her new middle school, and after evaluating Schuyler's abilities on a few different possible choices, it was decided that percussion will be the best choice. Schuyler the drummer girl. Just imagine it.

I like this band director; I'm hopeful that she will operate in a spot somewhere between the two extremes of "I have contest coming up, I don't have time to coddle a special ed student" (there's some of that out there, I'm sorry to say) on one hand, and on the other, a brand of "inclusion" that involves parking the kid with the disability in the corner with a chair and a rubber triangle. I think this director is going to be demanding of Schuyler and is going to help her learn how to focus. I think she's going to give Schuyler a chance. She might even overbelieve just a little.

At this year's IEP, we'll be changing Schuyler's team dramatically. This will be her last IEP meeting at the school that has, for all our recent disagreement, taken better care of Schuyler than most broken children ever experience. But after last year's attempt to stamp Schuyler as MR by the diagnostician, with the tacit agreement of other members of the team, there has been a serious divergence between the school's philosophy for Schuyler and ours.

Will that continue with next year's team? Or can we assemble a team of overbelievers, a group that will be less interested in trying to determine what Schuyler is incapable of doing and instead try to determine what she already knows and how to build from there?

I live in hope. As Shakespeare says, all men, I hope, live so.

At this year's IEP, we'll be changing Schuyler's team dramatically. This will be her last IEP meeting at the school that has, for all our recent disagreement, taken better care of Schuyler than most broken children ever experience. But after last year's attempt to stamp Schuyler as MR by the diagnostician, with the tacit agreement of other members of the team, there has been a serious divergence between the school's philosophy for Schuyler and ours.

Will that continue with next year's team? Or can we assemble a team of overbelievers, a group that will be less interested in trying to determine what Schuyler is incapable of doing and instead try to determine what she already knows and how to build from there?

I live in hope. As Shakespeare says, all men, I hope, live so.

March 25, 2011

Have you ever seen Office Space?

Here's an embarrassing but perhaps amusing story for you. (Before you ask, no, Schuyler was not home for this incident. It would not have happened if she had been.)

This afternoon, I lost my shit. Julie was on the phone trying to accomplish an important task with a customer service rep who seemed to be doing everything in her power to obstruct said task. She was in full-on "There's nothing I can do" mode, with that tone that suggests she wished our names were Mr. and Mrs. GoFuckYourself since that's clearly what she wanted to say. At the conclusion of the conversation, when the person had succeeded in making Julie actually cry, I needed to print something off, and at this tense, unhappy moment, our printer decided that it was no longer in the business of printing.

It was a very poorly timed print error.

So yeah, I lost it. I cursed at the printer, and I hit it. Okay, I may have hit it a couple of times, but when the flimsy shelf on which it sat suddenly gave way, that was it. Swearing dramatically and creatively, I proceeded to stomp on the printer, repeatedly, feeling it crunch beneath my feet, hearing it make a sound that, while not as satisfying as the sound of printing might have been a few moments before, was nevertheless a wonderful guilty pleasure. I lost my temper in the most ridiculous, over-the-top way, and that was that for the printer.

When I got my sudden flash of anger under control, I looked over at Julie sheepishly. "Want to join in?" I asked weakly. Without a word and with a stoic expression, she quietly stood and walked into the other room without answering.

I started to get up to follow her, to apologize for my shameful, destructive outburst, but before I could take more than a step or two, she returned from the bedroom.

With a softball bat. Which she put to astonishingly effective use.

Anyway, our printer most definitely doesn't work now. But I think we both feel much, much better.

March 23, 2011

The Dad Zone

Well, here we are. This morning saw an event that has loomed in the future, not as a bad thing, but just a thing. Today, Schuyler reached an important milestone in every pre-teen girl's life. You know what I'm talking about. Her crazy ride into young womanhood has begun.

(Note: Before the Corps of Righteous Indignation fires up the eFinger of Scoldage, yes, I did ask Schuyler if I could talk about this.)

When I mentioned this on Facebook, I got some interesting reactions. One was that they couldn't believe I was talking about it on Facebook, even after I pointed out that Schuyler knew I was doing so.

(Note: Before the Corps of Righteous Indignation fires up the eFinger of Scoldage, yes, I did ask Schuyler if I could talk about this.)

When I mentioned this on Facebook, I got some interesting reactions. One was that they couldn't believe I was talking about it on Facebook, even after I pointed out that Schuyler knew I was doing so.

You can disagree with my choice to write in such detail about Schuyler's life; that's a valid discussion, and one that I've had from time to time.

But if I am going to write about the milestones in her life, why wouldn't I include the positive, non-disability ones as well? It's personal, to be sure, but I'm not sure it's more personal than the things that she has no choice but to expose every day, just by virtue of the fact that she attends a special education class and talks with an electronic device and a robot voice. And really, I think the reason she didn't mind was simply that from the moment we figured out what was going on, we presented it to her as something positive, something cool, to be celebrated. She told us that she was scared, but also that she was excited.

Schuyler is always very concerned about being taken seriously as a Big Girl, and once we explained what this meant, she stood a little taller and embraced the positives of the moment. I realize that will probably fade in a hurry, especially as the reality of the experience sinks in, but she's starting off from a place of celebration, not shame, and while I admit that we've gotten some things wrong in the past, I think we got this moment right. High fives, Team RumHud.

The other reaction I got, one that I suppose I should have seen coming, could be expressed along the lines of "Ooo, do you think you'll be able to handle this, Dad? Just wait until you have to deal with feminine hygiene products!" (Cue sinister music.)

Sigh.

So let me make this clear. No, I don't love the fact that Schuyler's entering this phase of her life, not least of all because for her, the hormonal changes that bring her first period may also be causing seizures or otherwise stirring her neurological processes in a way that no one can predict or prevent. Puberty's a lot less amusing when it bares a monster's tooth and claw.

But for me, the anxiety I felt this morning mostly grew out of the unavoidable reality that Schuyler is growing up, quickly and wildly, and the days when her otherworldliness is cute are rapidly running out. And more narcissistically, it makes me feel old. REALLY old. That's a universal Dad experience, I guess, with or without a disability. My little girl isn't going to be a little girl much longer. Perhaps she already isn't, and hasn't been for a while.

So yeah, this makes me twitch a little. Maybe more than a little. But it's not because I have some inexplicable fear of icky girl stuff. Is that really supposed to be my reaction? "Ew ew ew, stop talkin' about it and turn on the ball game already! Jesus Christ, woman..." Someone asked if I would be capable of going to the store and buying "supplies" if Julie couldn't. Really? Why wouldn't I? Someone else pointed out that as a man, I wouldn't necessarily know what to get. Which is very true. Which is why I would ask. I don't drink coffee, either, but I still buy it for Julie when I go to the store. I can read a shopping list. I can absorb information when presented to me. Honestly, I'm baffled that this would even come up, and yet part of me understands perfectly. But it's still bullshit.

So let me ask you, Society. Do you want fathers to be involved in the lives of their daughters? Then you have to let go of the Big Dumb American Dad narrative. You have to forget about Fred Flintstone, Homer Simpson, and the cast of every stupid "Tyler Perry Presents..." show on TBS. Because I do whatever Schuyler needs me to do, and in the past that has included taking her to buy new bras. Yes, I realize that everyone's comfort level will obviously be higher when Julie takes the lead on this particular issue (there's progressive, and then there's pragmatic), but this isn't something that's permanently outside The Dad Zone. It's ALL in The Dad Zone. When Schuyler needs help with this, if I'm the one here, then I'll be the one to help her.

And here's the thing. That's true of every other father I know. The only fathers I know of whom this might not be true are a generation apart, maybe two generations, and honestly, I suspect most of them would step up when the situation called for it, too. I'll make a big, overly generalized statement here, while I'm at it. If you're a father here in the year 2011 and you're NOT comfortable helping your daughter with "girl stuff"? You need to GET comfortable with it. It's your goddamn job. You're not being cute if you run away from it. You're being a shitty dad. And you're kind of a shitty mom if you let him get away with that.

Sorry, but that's my snotty opinion. You know where to send the hate mail.

But if I am going to write about the milestones in her life, why wouldn't I include the positive, non-disability ones as well? It's personal, to be sure, but I'm not sure it's more personal than the things that she has no choice but to expose every day, just by virtue of the fact that she attends a special education class and talks with an electronic device and a robot voice. And really, I think the reason she didn't mind was simply that from the moment we figured out what was going on, we presented it to her as something positive, something cool, to be celebrated. She told us that she was scared, but also that she was excited.

Schuyler is always very concerned about being taken seriously as a Big Girl, and once we explained what this meant, she stood a little taller and embraced the positives of the moment. I realize that will probably fade in a hurry, especially as the reality of the experience sinks in, but she's starting off from a place of celebration, not shame, and while I admit that we've gotten some things wrong in the past, I think we got this moment right. High fives, Team RumHud.

The other reaction I got, one that I suppose I should have seen coming, could be expressed along the lines of "Ooo, do you think you'll be able to handle this, Dad? Just wait until you have to deal with feminine hygiene products!" (Cue sinister music.)

Sigh.

So let me make this clear. No, I don't love the fact that Schuyler's entering this phase of her life, not least of all because for her, the hormonal changes that bring her first period may also be causing seizures or otherwise stirring her neurological processes in a way that no one can predict or prevent. Puberty's a lot less amusing when it bares a monster's tooth and claw.

But for me, the anxiety I felt this morning mostly grew out of the unavoidable reality that Schuyler is growing up, quickly and wildly, and the days when her otherworldliness is cute are rapidly running out. And more narcissistically, it makes me feel old. REALLY old. That's a universal Dad experience, I guess, with or without a disability. My little girl isn't going to be a little girl much longer. Perhaps she already isn't, and hasn't been for a while.

So yeah, this makes me twitch a little. Maybe more than a little. But it's not because I have some inexplicable fear of icky girl stuff. Is that really supposed to be my reaction? "Ew ew ew, stop talkin' about it and turn on the ball game already! Jesus Christ, woman..." Someone asked if I would be capable of going to the store and buying "supplies" if Julie couldn't. Really? Why wouldn't I? Someone else pointed out that as a man, I wouldn't necessarily know what to get. Which is very true. Which is why I would ask. I don't drink coffee, either, but I still buy it for Julie when I go to the store. I can read a shopping list. I can absorb information when presented to me. Honestly, I'm baffled that this would even come up, and yet part of me understands perfectly. But it's still bullshit.

So let me ask you, Society. Do you want fathers to be involved in the lives of their daughters? Then you have to let go of the Big Dumb American Dad narrative. You have to forget about Fred Flintstone, Homer Simpson, and the cast of every stupid "Tyler Perry Presents..." show on TBS. Because I do whatever Schuyler needs me to do, and in the past that has included taking her to buy new bras. Yes, I realize that everyone's comfort level will obviously be higher when Julie takes the lead on this particular issue (there's progressive, and then there's pragmatic), but this isn't something that's permanently outside The Dad Zone. It's ALL in The Dad Zone. When Schuyler needs help with this, if I'm the one here, then I'll be the one to help her.

And here's the thing. That's true of every other father I know. The only fathers I know of whom this might not be true are a generation apart, maybe two generations, and honestly, I suspect most of them would step up when the situation called for it, too. I'll make a big, overly generalized statement here, while I'm at it. If you're a father here in the year 2011 and you're NOT comfortable helping your daughter with "girl stuff"? You need to GET comfortable with it. It's your goddamn job. You're not being cute if you run away from it. You're being a shitty dad. And you're kind of a shitty mom if you let him get away with that.

Sorry, but that's my snotty opinion. You know where to send the hate mail.

March 20, 2011

Enough

That night, we quietly talked about how we wanted to raise our kid, a child who was both completely theoretical in our minds and yet sitting right there in the room with us, floating serenely a world away and at the same time no distance from us at all, just Not-Yet-Schuyler and the little secret monster inside her tiny, forming head.

We talked about conversations we would have with our child one day, decisions we'd make with that kid, the things we thought she would do, the rules on which we would stand firm and the rules we'd never even lay down in the first place. We wondered what our kid would call us (Mom? Dad? Mommy? Rob and Julie? Did we care?), what kind of half-Midwestern, half-Texas accent she might develop. We talked about our ridiculous ideas for what would make a kid succeed. I was steadfast that ours would be a Disney-free home (ha); Julie declared that she would only give Schuyler hand-crafted toys. (She actually tried this, but Schuyler hated them. To this day, there are few toys that excite Schuyler as much as a crappy piece of My Little Pony plastic from a Happy Meal.)

That night, in the dark, we tried to push back some of the uncertainty of what lay ahead of us by constructing a little pretend future. It didn't matter if things turned out the way we imagined. We didn't know if things were going to be okay, although we had no reason to think they wouldn't. We simply had to believe they might, and that was enough.

-----

Tonight we step into Schuyler's room to turn off the tiny pink lights that we hung in her room at Christmas, the lights that she asks us to leave on every night when she goes to bed. I can't imagine she wants them on because she's scared. She wants them on, I think, because they give her the light she requires as she has her quiet conversations with her dolls and her animals and her monsters and dinosaurs before she goes to sleep. She wants them on because they are pink, and pink is still cool, the coolest thing there is.

We turn off the lights, and Julie says, "She's sleeping with her witch." Sure enough, Schuyler has dug out her little Groovy Girl witch and is holding it close to her chest. Julie leaves the room, but I stay for a while. I lay down beside Schuyler and we sit in the dark together. She wakes just enough to talk with me, about her witch and Supermoon and what she's going to dream about. She curls up beside me and goes to sleep again, her witch still clutched tight, and doesn't wake when I leave.

And it strikes me tonight, as it does on many nights, on most nights, even, that more than ever, I still don't know if things are going to be okay. Unlike that night almost twelve years ago, I have reasons to believe they won't be.

And like way back then, I just have to believe, with a little more desperation and a lot fewer threads to grasp than before, that things just might be okay. And like that long ago night, it might just be enough.

March 15, 2011

The Ifs and the I Don't Knows

Waiting two months to see a neurologist sounds like a long time, even though I'm told that it's really not. Well, it is a long time, but I guess I should say that it's not an unusual wait; it's actually pretty good compared to the wait that many parents and patients endure. Most people end up waiting months, and that's right here in America. I can't tell you how many times I've read conservatives disparaging the Canadian health care system's long waits when they are listing the failures of socialized medicine. As far as I can tell, the big difference between that system and the one we have here in God's Perfect Perfect Country is the fact that we'll get a gigantic bill for our trouble. Well, what are you going to do?

It's frustrating, in part because we're trying to catch a very elusive monster. Schuyler hasn't had consistent issues with this, after all. She had a few "incidents" back in January, and then again two weeks ago (and twice last week since I last wrote about this). This week? Nothing so far. What we'll be hoping for is IF she's having seizures, and we don't know that she is, she'll just happen to have one of them while she has wires connected to her head in about six weeks. If we could have gone to the neurologist's office when she was having these incidents, then we would have a better shot at catching one as it happens. Doing it this way is like finding evidence of some animal in the forest and then returning with a gun two months later, hoping it might come back. And not knowing if it's a rabbit or a bear. Or a Tyrannosaur.

Identifying absence seizures is hard because they are so hard to recognize, and in Schuyler's case, the evidence that she might have had one follows the actual seizure itself, IF she's having them. If if if if if if if. Fucking ifs rule our lives now.

I don't know if she's having seizures. We continue to rule out the other possibilities, such as UTIs and blood sugar issues, but that process of elimination isn't much help. From what I've read, it's not unusual for absence seizures to go unrecognized or unobserved for years. Do you know when some kids discover they're having them? When they start driving. Think about that. Spacing out for a few seconds in class or at home goes unnoticed for years, easily, but imagine your child having one at 70 mph on the freeway. Assuming your kid survives, congratulations! Now you know they're having seizures.

Well, Schuyler's eleven, and she still doesn't ride a bicycle, so that's a fun fear that I can put off for a while. It's good to pace yourself, after all.

When we learned of Schuyler's polymicrogyria almost eight years ago (God, I can't believe it's been that long), this wasn't what we expected. I suspect that's true for a lot of parents. You imagine the Big Event, you imagine that first seizure arriving like a hurricane or an earthquake. You don't think about the possibility that you just might not know, it might take years to discover the truth.

There's a lot I don't know. I don't know if Schuyler is having seizures. I don't know if she's significantly (and permanently) impaired intellectually. Will she ever catch up to her classmates? Will she graduate from high school one day? Will she drive a car and live in an apartment and have a job? Will she date boys and get married? Will she date girls and scandalize her grandparents? When I die, will she cry her tears and then move on with her independent life? Will the monster that holds her back now begin to gently release its grip on her as she gets older, or will it one day crush her in its hands? I don't know. I can't know.

Other parents worry about their neurotypical or otherwise unafflicted children's futures, I get that. But not like this. I wish I knew how to explain to those parents, the ones who try to cheer us up by telling us how they worry about their kids, too, just like us, that no, they don't. I wish I could make them see that the things that worry them, things like good grades or their daughters' first periods or their kids' lives after high school, these things terrify us. Even the usual stuff is hard, the stuff we can see coming. The thing you learn with a kid like Schuyler is that even the boring stuff goes down differently with her. You think you know how it'll play out, but you don't.

Sometimes I feel like the worst thing that happened to Schuyler was simply that she was our first born. After Schuyler, we made the decision not to risk more children, and while that has been a source of some sadness over the years, it was nevertheless exactly the correct choice to make. But if we'd had another child before Schuyler, if she had an older, neurotypical sibling, then at least she wouldn't be as alone as she is. I don't know, though. Maybe it wouldn't be any better. Schuyler is loved by a great many people, including members of her family, but the harsh truth is that the reality of her situation is understood by very very few. Our friends, our co-workers, and both our families want to get it, to get her, but they don't. And really, I don't know that they can.

Because honestly, I don't know that Julie or I do, either, although I know we get closer than anyone else. Some of her teachers have probably gotten close from time to time, too. The hope and the enthusiasm we all felt when we first moved to Plano has been replaced by some grey truths. Schuyler can be difficult to teach. Schuyler can be age-appropriate in some ways and astonishingly delayed in others. A world in which she can attend mainstream classrooms and learn alongside her neurotypical classmates seems more out of reach now than ever before. And she might be having seizures.

Sometimes when I write about Schuyler, I have a point that I'm trying to make. I take my topic and I use my skills as a writer to present it, sculpted and shaped into something that works as an essay, something that might have meaning and value to others. But every now and then, when I feel overwhelmed both by the way things are and the unknown and the unknowable, I just start writing, just let my anxieties flow out without shape or craft. No art, just "fuck".

Sorry, but yeah. Fuck.

It's frustrating, in part because we're trying to catch a very elusive monster. Schuyler hasn't had consistent issues with this, after all. She had a few "incidents" back in January, and then again two weeks ago (and twice last week since I last wrote about this). This week? Nothing so far. What we'll be hoping for is IF she's having seizures, and we don't know that she is, she'll just happen to have one of them while she has wires connected to her head in about six weeks. If we could have gone to the neurologist's office when she was having these incidents, then we would have a better shot at catching one as it happens. Doing it this way is like finding evidence of some animal in the forest and then returning with a gun two months later, hoping it might come back. And not knowing if it's a rabbit or a bear. Or a Tyrannosaur.

Identifying absence seizures is hard because they are so hard to recognize, and in Schuyler's case, the evidence that she might have had one follows the actual seizure itself, IF she's having them. If if if if if if if. Fucking ifs rule our lives now.

I don't know if she's having seizures. We continue to rule out the other possibilities, such as UTIs and blood sugar issues, but that process of elimination isn't much help. From what I've read, it's not unusual for absence seizures to go unrecognized or unobserved for years. Do you know when some kids discover they're having them? When they start driving. Think about that. Spacing out for a few seconds in class or at home goes unnoticed for years, easily, but imagine your child having one at 70 mph on the freeway. Assuming your kid survives, congratulations! Now you know they're having seizures.

Well, Schuyler's eleven, and she still doesn't ride a bicycle, so that's a fun fear that I can put off for a while. It's good to pace yourself, after all.

When we learned of Schuyler's polymicrogyria almost eight years ago (God, I can't believe it's been that long), this wasn't what we expected. I suspect that's true for a lot of parents. You imagine the Big Event, you imagine that first seizure arriving like a hurricane or an earthquake. You don't think about the possibility that you just might not know, it might take years to discover the truth.

There's a lot I don't know. I don't know if Schuyler is having seizures. I don't know if she's significantly (and permanently) impaired intellectually. Will she ever catch up to her classmates? Will she graduate from high school one day? Will she drive a car and live in an apartment and have a job? Will she date boys and get married? Will she date girls and scandalize her grandparents? When I die, will she cry her tears and then move on with her independent life? Will the monster that holds her back now begin to gently release its grip on her as she gets older, or will it one day crush her in its hands? I don't know. I can't know.

Other parents worry about their neurotypical or otherwise unafflicted children's futures, I get that. But not like this. I wish I knew how to explain to those parents, the ones who try to cheer us up by telling us how they worry about their kids, too, just like us, that no, they don't. I wish I could make them see that the things that worry them, things like good grades or their daughters' first periods or their kids' lives after high school, these things terrify us. Even the usual stuff is hard, the stuff we can see coming. The thing you learn with a kid like Schuyler is that even the boring stuff goes down differently with her. You think you know how it'll play out, but you don't.

Sometimes I feel like the worst thing that happened to Schuyler was simply that she was our first born. After Schuyler, we made the decision not to risk more children, and while that has been a source of some sadness over the years, it was nevertheless exactly the correct choice to make. But if we'd had another child before Schuyler, if she had an older, neurotypical sibling, then at least she wouldn't be as alone as she is. I don't know, though. Maybe it wouldn't be any better. Schuyler is loved by a great many people, including members of her family, but the harsh truth is that the reality of her situation is understood by very very few. Our friends, our co-workers, and both our families want to get it, to get her, but they don't. And really, I don't know that they can.

Because honestly, I don't know that Julie or I do, either, although I know we get closer than anyone else. Some of her teachers have probably gotten close from time to time, too. The hope and the enthusiasm we all felt when we first moved to Plano has been replaced by some grey truths. Schuyler can be difficult to teach. Schuyler can be age-appropriate in some ways and astonishingly delayed in others. A world in which she can attend mainstream classrooms and learn alongside her neurotypical classmates seems more out of reach now than ever before. And she might be having seizures.

Sometimes when I write about Schuyler, I have a point that I'm trying to make. I take my topic and I use my skills as a writer to present it, sculpted and shaped into something that works as an essay, something that might have meaning and value to others. But every now and then, when I feel overwhelmed both by the way things are and the unknown and the unknowable, I just start writing, just let my anxieties flow out without shape or craft. No art, just "fuck".

Sorry, but yeah. Fuck.

March 4, 2011

Polly

You watch for the big monsters. You brace for them, wait for them to come so you can wrestle with them, your feet firmly in place, set for the match. But the thing is, when they arrive, they never feel like big monsters. They don't even reveal themselves all at once. They quietly walk into the room, never in the light but rather in the shadows at the edges. It can take a long time to notice that they're even there, and to identify what they are.

Two years ago, we faced the possibility that Schuyler was beginning to have absence seizures. This was tough, but not unexpected; the majority of kids with polymicrogyria, as many as 85-90% of them, develop seizures. Over the next couple of months, we went trough the whole process of EEG evaluation, including a fun test where Schuyler had wires glued to her head for a whole weekend. That test was ultimately inconclusive. It didn't record any outright seizures, but it did show a "significant neurological event" occurring periodically on the left side of her brain while she slept. Her neurologist had no idea what it was, only what it wasn't. No seizures, not yet, but maybe... something.

I hate writing about something that might embarrass Schuyler one day, but it's kind of hard to avoid at this point, so I apologize in advance. A few weeks ago, out of the blue, Schuyler had an accident. She peed her pants. A few days later, it happened again. Both times she said she tried to get to the bathroom in time, but didn't make it. She explained, as best as she could, that it just happened. One minute she didn't have to go, and the next, it was too late.

Last night, at the house of a friend, it happened again, catching her completely by surprise. And then tonight, after we got home from school, one minute she was sitting down with her Happy Meal, and the next, she was running to the bathroom, in vain. Another accident.

On none of these occasions was anyone actively observing her in the exact moment. But we know the warning signs; we've known them for years, always kept them in the back of our minds.

So again we brace ourselves, not for that often-imagined moment when Schuyler falls to the floor in a grand mal seizure and suddenly It Has Come, but rather for the suspicion, the realization that something may already be happening, that the odds may have caught up with her at last. Last time, we wondered because Schuyler had been spacing out from time to time. This time, the signs are even more compelling. And again, we'll put Schuyler in the hands and the sensors of a neurology team in the hopes that they may have their crown of wires attached to her at an opportune moment so that we can finally know if this is beginning in earnest.

Schuyler is eleven now, and we believe that she's old enough for a little more adult conversation about this. She's known about her condition for a while. A number of people have written to me over the years, afraid that words like "broken" and "monster" were going to scar her somehow, but the fact is that we've had some version of this conversation going with her all along. People afraid of how Schuyler might feel if she read my words one day are missing the point. She's been hearing the words, she's been soaking up the concept. Hiding her reality from her would be wrong, and it would be pointless. She faces the big truths in her own way; she processes them in her own time.

She was feeling humiliated by her accident tonight, as she had the night before, so I sat down with her and explained that these accidents might not be her fault. I told her that the same thing in her brain that makes it hard for her to speak clearly, the thing that causes her to drool sometimes and keeps her from eating some foods, that thing might also be causing her to pee her pants every now and then. I explained how our brains run on electricity (which she thought was pretty cool), and that some brains use too much electricity sometimes, which causes them to overload. Those overloads are called seizures, I told her. Some of them are brief and small, so small that the person doesn't know that they had them, while others are bigger.

I told her that we will have to see a doctor again to be sure, but that she might be having those little seizures, and if she is, that might be causing her to pee her pants. I told her that these seizures were cause by the thing in her brain that made her different.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"What's what called?"

She pointed to her head. "The little monster in my brain."

It occurred to me that I might not have ever actually told her this part. "It's got a long name, it's called polymicrogyria."

She thought about that for a moment, and then laughed. "That's a funny name," she said.

"Do you want to call it something else?" I asked.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"Polymicrogyria."

She laughed. "I know, I know!" (She says "I know, I know!" a lot when she gets excited.) "It's Polly the Monster!"

I see a monster that may finally be giving my little girl seizures, might be delivering on the ugly promise we'd been made when Schuyler was diagnosed almost eight years ago, and I feel my heart drop again.

Schuyler sees that monster, and she nicknames it Polly.

As we drove to pick up Julie at work, Schuyler sat quietly in the passenger seat, processing. Finally she turned to me.

"Daddy? I don't want a little monster in my brain."

She said it seriously but not somberly, sad but not crushed. I told her that I didn't want her to have it, either, but there was nothing we could do but make the very best of it, the same as we always had.

She shrugged a little and said, "I know."

Later, she asked Julie if she was sad. She said it with concern for her mother, but I didn't get the sense that she was terribly sad herself. I mean, she wasn't thrilled by this new situation, but she was processing it already, moving faster than we were, perhaps sensing that some very hard stuff may be waiting in the near future but already impatient with the sad.

"I know." She knows.

Two years ago, we faced the possibility that Schuyler was beginning to have absence seizures. This was tough, but not unexpected; the majority of kids with polymicrogyria, as many as 85-90% of them, develop seizures. Over the next couple of months, we went trough the whole process of EEG evaluation, including a fun test where Schuyler had wires glued to her head for a whole weekend. That test was ultimately inconclusive. It didn't record any outright seizures, but it did show a "significant neurological event" occurring periodically on the left side of her brain while she slept. Her neurologist had no idea what it was, only what it wasn't. No seizures, not yet, but maybe... something.

I hate writing about something that might embarrass Schuyler one day, but it's kind of hard to avoid at this point, so I apologize in advance. A few weeks ago, out of the blue, Schuyler had an accident. She peed her pants. A few days later, it happened again. Both times she said she tried to get to the bathroom in time, but didn't make it. She explained, as best as she could, that it just happened. One minute she didn't have to go, and the next, it was too late.

Last night, at the house of a friend, it happened again, catching her completely by surprise. And then tonight, after we got home from school, one minute she was sitting down with her Happy Meal, and the next, she was running to the bathroom, in vain. Another accident.

On none of these occasions was anyone actively observing her in the exact moment. But we know the warning signs; we've known them for years, always kept them in the back of our minds.

Typical absence seizures are primary generalized seizures characterized by brief staring episodes, lasting two to 15 seconds (generally less than 10 seconds), with impaired consciousness and responsiveness. They begin without warning (no aura) and end suddenly, leaving the person alert and without postictal confusion. Often, the person will resume preattack activities, as if nothing had happened. Simple absence seizures are characterized by staring spells alone. In complex absence seizures, which are more common, staring is accompanied by automatisms, such as eye blinks or lip smacking; they may include mild clonic, atonic, or autonomic components involving the facial muscles. There may also be a slight nod of the head or semi-purposeful movements of the mouth or hands. The automatisms tend to be stereotyped, with the same behaviors occurring during each seizure. Penry et al observed automatisms in 63% of all absence seizures. However, the automatisms are less elaborate than those observed with complex partial seizures. There may also be autonomic manifestations, such as pupil dilation, flushing, tachycardia, piloerection, salivation, or urinary incontinence.

"Absence Seizures and Syndromes: An Overview", from Perspectives in Pediatric Neurology

So again we brace ourselves, not for that often-imagined moment when Schuyler falls to the floor in a grand mal seizure and suddenly It Has Come, but rather for the suspicion, the realization that something may already be happening, that the odds may have caught up with her at last. Last time, we wondered because Schuyler had been spacing out from time to time. This time, the signs are even more compelling. And again, we'll put Schuyler in the hands and the sensors of a neurology team in the hopes that they may have their crown of wires attached to her at an opportune moment so that we can finally know if this is beginning in earnest.

Schuyler is eleven now, and we believe that she's old enough for a little more adult conversation about this. She's known about her condition for a while. A number of people have written to me over the years, afraid that words like "broken" and "monster" were going to scar her somehow, but the fact is that we've had some version of this conversation going with her all along. People afraid of how Schuyler might feel if she read my words one day are missing the point. She's been hearing the words, she's been soaking up the concept. Hiding her reality from her would be wrong, and it would be pointless. She faces the big truths in her own way; she processes them in her own time.

She was feeling humiliated by her accident tonight, as she had the night before, so I sat down with her and explained that these accidents might not be her fault. I told her that the same thing in her brain that makes it hard for her to speak clearly, the thing that causes her to drool sometimes and keeps her from eating some foods, that thing might also be causing her to pee her pants every now and then. I explained how our brains run on electricity (which she thought was pretty cool), and that some brains use too much electricity sometimes, which causes them to overload. Those overloads are called seizures, I told her. Some of them are brief and small, so small that the person doesn't know that they had them, while others are bigger.

I told her that we will have to see a doctor again to be sure, but that she might be having those little seizures, and if she is, that might be causing her to pee her pants. I told her that these seizures were cause by the thing in her brain that made her different.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"What's what called?"

She pointed to her head. "The little monster in my brain."

It occurred to me that I might not have ever actually told her this part. "It's got a long name, it's called polymicrogyria."

She thought about that for a moment, and then laughed. "That's a funny name," she said.

"Do you want to call it something else?" I asked.

"What's it called?" she asked.

"Polymicrogyria."

She laughed. "I know, I know!" (She says "I know, I know!" a lot when she gets excited.) "It's Polly the Monster!"

I see a monster that may finally be giving my little girl seizures, might be delivering on the ugly promise we'd been made when Schuyler was diagnosed almost eight years ago, and I feel my heart drop again.

Schuyler sees that monster, and she nicknames it Polly.

As we drove to pick up Julie at work, Schuyler sat quietly in the passenger seat, processing. Finally she turned to me.

"Daddy? I don't want a little monster in my brain."

She said it seriously but not somberly, sad but not crushed. I told her that I didn't want her to have it, either, but there was nothing we could do but make the very best of it, the same as we always had.

She shrugged a little and said, "I know."

Later, she asked Julie if she was sad. She said it with concern for her mother, but I didn't get the sense that she was terribly sad herself. I mean, she wasn't thrilled by this new situation, but she was processing it already, moving faster than we were, perhaps sensing that some very hard stuff may be waiting in the near future but already impatient with the sad.

"I know." She knows.

February 15, 2011

Helicopters

There's been a recurring theme recently in disability blogs and other online forums. Writers, mostly parents, are making lists of "Things You Shouldn't Say to Parents of Kids with Disabilities". I'm not usually a joiner in this sort of thing, but the other day I realized that apparently I do have something to contribute to these lists.

We met the band director at Schuyler's new middle school, and it went pretty well. She didn't roll her eyes at us, she seemed genuinely interested in learning more about Schuyler and was very willing to set up a meeting with us. It was a very promising start. This band thing has the potential to really make a difference in Schuyler's life, so we are taking it very seriously. We were looking forward to attending the demonstration concert with Schuyler and her class this week until we received a note from the elementary school music teacher who is organizing Schuyler's school's part of this trip. In the middle of the note (sent home to everyone, I should add, not just us), it said simply "Due to limited space, parents are not invited to attend."

I'm not sure if it was the way the note was worded or our past experience with previous schools where parents weren't encouraged to attend classroom events. But something about that note made us dig in our heels a bit. And when I wrote to the teacher and explained why we felt it was important and appropriate for us to be there, her reply demonstrated a certain amount of dug in heels as well. The field trip is on Wednesday; perhaps I will have stories to share with you then. We are planning to attend and have informed the school of this. So there you go.

Now, this isn't a story about why this is or isn't an appropriate position for us to take. I'm sure I'll hear from some of you anyway, but I'm pretty solid with this. I think that with the exception of tests being administered or the like, any school function should be open to attendance by interested parents. That's just a given to me. Saying that there's limited space is frankly just weak.

No, this is a story about me writing a short note about this on Facebook and having someone respond that the schools wisely limit parent involvement to these things because of "helicopter parents" who hover and try to influence their kids and interfere with their independence. It was then that I mentally caught something that had tweaked me for years but I was only now able to identify. It became my "Thing Not to Say to the Parents of a Special Needs Kid."

The term "helicopter parents" is meaningless, inappropriate and insulting to parents of kids with disabilities. Don't say it to us. Don't even think it about us. Save it for Toddlers & Tiaras.

As parents of special needs kids, we hover because integration into school programs like band is incredibly important to our children. It is the thing that can release them from the gentle ghetto of special education classes that can become their parking place until they are old enough for the public schools to relinquish responsibility and return them to "Your Problem" status. We hover because we've seen what happens when we don't. We've seen what happens in even the best programs when a child is difficult to teach and no one is looking. We hover because we can remember past schools in past towns where our child was forgotten in the corner because she was a broken child, but a polite and quietly broken one who didn't require constant attention and protection. We hover, not because we don't want our kids to become independent, but because we desperately want them to be, and we know the paths that are most likely to lead them there. We hover because history has shown all of us that if we don't watch out for our kids, sometimes they don't get watched out for.

We don't just hover. We monitor, we observe, we interfere when necessary, and we educate ourselves so that we are able to identify those times when it becomes necessary. Our complete and total involvement with our kids' school experience is not negotiable. Special needs parents are experts in the one thing that even the best schools will never master. We know our kids. More to the point, we know their monsters. And if we believe that we need more information on how a program works or how it is going to affect our child, it is inappropriate to tell us that we're not invited, we're not needed, they've got a handle on this, there's nothing for us to worry about.

Are we a pain in the ass to the schools where Schuyler has attended? If we are, then it's because someone has forgotten that we are part of her team. Someone has let themselves be fooled into thinking that they know what's best for her and that she is like any other kid they've taught. Any time a teacher thinks that past experience tells them all they need to know about teaching a child, they have already failed. This is true of any student, but it is true a hundred times over for a child with a disability. Every broken child is broken in their own way. Every single one of them.

So special needs parents become helicopter moms and dads, if that's how you want to look at it. But if that's how you see us, I hope that you'll keep that opinion to yourself. Unless you are one of our kids' teachers. In that case, I hope you will keep that opinion to yourself, AND get the hell out of the way.

February 11, 2011

Pimpage

Both this blog and my book have made it to the finals of the About.com Readers' Choice Awards. It would be extra super swell if you'd go vote. You can do so once a day, every day through March 8. The winners will be announced on March 15.

Thank you kindly for your support, yo.

February 6, 2011

January 30, 2011

“Is it better to out-monster the monster or to be quietly devoured?”

I got a reasonable, respectfully worded comment (God, how refreshing) regarding my terminology which I felt deserved an equally reasonable and respectfully response. By the time I was finished, it had gotten far too long for a comment. And while I've written about this before, at length, it's an important point and probably deserves to be revisited from time to time. I felt like it certainly deserved its own post. So here we go...

---

Of course you are entitled to your opinion and your disagreement, and I thank you for posting. A few thoughts:

You're absolutely right, there is no predicting how Schuyler will feel about anything I've written about her and her condition. That point has been made in countless "How is she going to feel one day when she reads...?" posts and emails and criticisms. It's a valid point. You have to remember, however, that our feelings and opinions and reactions to Schuyler's situation aren't happening in a vacuum. I'm not writing one thing and saying another to her. From the very beginning, she has been raised to understand that no, she's not like other kids and yes, she has to work hard to overcome the obstacles that are in her way.

Schuyler knows that there's something wrong with her brain, she understands better than you or me or anyone else how true that is. She may choose to see it differently as she gets older, but she'll make that determination on her own. And she'll do so knowing that her parents love her and are inspired by her. The idea that she will one day read something I wrote and suddenly she'll know some dark secret about how I visualized her disorder is absurd. She already knows what the title of the book refers to; it was her metaphor originally, after all. We don't keep anything from her regarding her condition. THAT would be offensive, wildly so. Schuyler's not a delicate flower. She's a tough kid, because she has to be, and she's also a realistic one.

People acting out of concern for Schuyler are certainly within their rights to do so. Concern that she will be somehow wounded by an acknowledgement of her very real, very hard condition is frankly insulting to her, though. It sells her short. It denies her very real ability to face her condition head on.

"I do feel it is important to hear the experiences and opinions of adults who have grown up with disabilities or differences (whatever they may be). I think theirs is the most relevant voice in this debate."

Their voices are both absolutely relevant, and at the same time completely beside the point. I hope you don't think that after all this time, I haven't been listening to the opinions of persons with disabilities, along with their families and caregivers. But the thing you might not understand is that if I've heard from a hundred people, I've heard about a hundred different opinions and perspectives. There is no consensus. Well, of course there isn't.

For every person who is inspired by the Holland poem, there are equal numbers who find it to be condescending and ridiculous. For every person who depends on their faith in God to sustain them, there's an equal number who feel like that God has turned his back on their loved ones, or who have lost their faith altogether. For every person with a disability who finds comfort in People First Language, there are equal numbers who self-identify with terms like "cripple". Which of these voices should dictate how my family and I deal with Schuyler's disability?