Tomorrow, we see Schuyler's neurologist.

Today, sidewalk chalk.

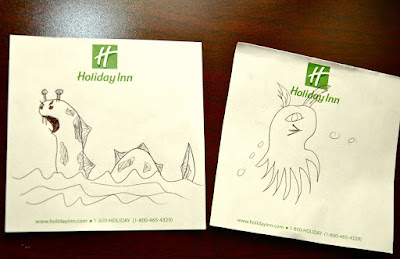

Schuyler is my weird and wonderful monster-slayer. Together we have many adventures.

For all my fancy book events and all my inspirational speeches and all my "gee, what a dad!" accolades, in the end I might be just like any other parent of a disabled child who has convinced themselves that the future is going to be easier, not harder, than the past and the present. I've looked at families with kids who sit solidly within that MR diagnosis and I've counted myself fortunate that my daughter has future options unavailable to them, but that might not really be true after all. It's entirely possible that I've stupidly and arrogantly pitied my own people.

My love for Schuyler has made me a believer and an unwavering advocate, but it might also be making me into a fool. And that's hard to face.

So how do I feel? I'm tired. It's exhausting, trying to build a fantasy world in which you child's disability isn't going to hold her back forever. It's a full-time job, convincing myself that everything's going to work out somehow and that one day she'll tell people "Why, there was a time when my teachers thought I was retarded, and look at me now! My parents believed in me, and they were right. I'd like to dedicate this Pulitzer to them."

And it requires a constant, unblinking effort to convince myself of the very very pretty lie that my little girl is going to be okay.

Typical absence seizures are primary generalized seizures characterized by brief staring episodes, lasting two to 15 seconds (generally less than 10 seconds), with impaired consciousness and responsiveness. They begin without warning (no aura) and end suddenly, leaving the person alert and without postictal confusion. Often, the person will resume preattack activities, as if nothing had happened. Simple absence seizures are characterized by staring spells alone. In complex absence seizures, which are more common, staring is accompanied by automatisms, such as eye blinks or lip smacking; they may include mild clonic, atonic, or autonomic components involving the facial muscles. There may also be a slight nod of the head or semi-purposeful movements of the mouth or hands. The automatisms tend to be stereotyped, with the same behaviors occurring during each seizure. Penry et al observed automatisms in 63% of all absence seizures. However, the automatisms are less elaborate than those observed with complex partial seizures. There may also be autonomic manifestations, such as pupil dilation, flushing, tachycardia, piloerection, salivation, or urinary incontinence.

"Absence Seizures and Syndromes: An Overview", from Perspectives in Pediatric Neurology

"I personally disagree with your use of the term "monster" to describe something that your child cannot separate from herself. This goes against every instinct I have. I am an educator but not a parent.

"I don't think most people (with the always exceptional minority of crazies) would argue this point with you out of spite or with the goal of proving you wrong but rather out of concern for your daughter and a hope that sharing one's own experience can make a difference in the life of another child and family going through a familiar struggle.

"However, there is no point arguing about it as only time will tell how your daughter will feel about it. I do feel it is important to hear the experiences and opinions of adults who have grown up with disabilities or differences (whatever they may be). I think theirs is the most relevant voice in this debate."

"What will become of your life when Schuyler's monster becomes her identity? Maybe she will grow to resent that you call what makes her a unique individual a 'monster' as if were a bad thing."Like I said, the idea of Schuyler's polymicrogyria as a kind of unique personality trait rather than a serious and potentially dangerous affliction is hardly a new one. And I'm sure that I've made it even easier to make that claim. I recently said the following, after all:

Schuyler's polymicrogyria isn't her greatest challenge, not any more. Her life doesn't seem to be in any real danger, with no apparent seizures yet, and her monster doesn't impede her everyday life with the ferocity that it does for so many other PMG kids. For that, I am grateful.I further explained that Schuyler's difference, her uniqueness, is something that I'm still thrilled by, and I consider it my distinct honor to be the person who gets to help lead her through a world that might not understand her difference, but which is nevertheless a much better, more vibrant place because of it.

All parents have a narrative for their children. Some are blatant and perhaps a little horrible, like the ones on a television show that Julie and I have recently become addicted to, about the parents of kids who play sports and who live out their own past failures or glory days through their own children. The rest of us watch them and say, "How awful!" and "My little girl is going to chart her own course, she’ll decide what her future's going to be all about, not me." But in our secret hearts, we whisper, "I hope she plays the trombone...." (No, I really do. I suspect Julie's secret heart and mine are whispering different things.)

-- excerpt from Schuyler's Monster

"Last night as I was sleeping, I dreamt -- marvelous error! -- that I had a beehive here inside my heart. And the golden bees were making white combs and sweet honey from my old failures."